It

was a crisp Fall day in October, as Hazel

mused over her life in Belmont and

Northport, Maine. She had recently observed

her seventy-second birthday five days

earlier. She and her family had celebrated

with a cake and ice cream. How she enjoyed

having the children round about.

Hazel had

been brought to Waldo County Hospital and

knew that she was in her last days,

suffering from cancer. She had lived a

rich, full life with all of its joys and

sorrows.

Hazel was

born in Belmont, the third child and

daughter of John W. and Jennie

(Levenseller) Morse, in the home of her

grandparents, Moses and Susan Morse. The

household was always hectic and busy. Gram

was raising several motherless cousins,

among whom were Gert, Maud, Fred, and

young Charlie, children of her Uncle Fred

whose wife, Cordelia, had died in

Massachusetts. Her cousins, Bill, Frank,

Georgie and Ruth were often in the home

since their mother’s death. Also in the

home were Hazel’s siblings, Susie, Bertha,

Clarence, Everett, Amon and Lester. Each

of the children had chores to do.

Hazel

recalled the day in 1902, when she and

cousin Ruth were four years old. Grampa

Moses Morse had walked home for lunch from

the Chenery farm on a hot spring day. The

children were all playing, laughing and

talking around the kitchen table when Ruth

called out to Gram that Grampa was asleep

as he sat at the kitchen table. What the

four-year olds didn’t realize, was that

Grampa had died.

Hazel

remembered the summer day that

two-year-old Amon was nowhere to be found.

Mamma was expecting her eighth child.

While they all searched for Amon, Hazel

and Bertha found him next-door at Aunt

Ada’s, asleep in the barn with a young

calf.

Mamma became

ill, possibly from worry, or from getting

wet, as they searched for the boy in the

wet grass from a light rain. Eight

year-old Hazel remembered that Gram,

looking very worried, was busy with Mamma

until Dr. Pearson came from Morrill. She

remembered hearing the cry of her new-born

baby brother. Soon the children were told

that Mamma had been taken to Heaven. Gram

hovered over the newborn, but two days

later, he, too, went to Heaven with Mamma.

Mamma was so pretty, and all these years

later, Hazel realized that her mother was

only thirty years old.

All of the

Morse siblings and cousins went to school

at the one-room schoolhouse on Greer’s

corner where her father, uncles and

cousins had gone before them. Cousin Ruth

lived in Waterville with her father,

Frank. One school year, Hazel lived with

them and attended the public school there.

A year after

Mamma’s death, Papa married his daughters’

friend, Mary Elizabeth Butler, who was

fifteen at the time. She was called May,

and only five years older than Hazel. Gram

was in charge of the household. May,

Susie, Bertha and Hazel became great

friends, working together to do household

chores for Gram. In 1910, May had a baby

girl, whom she named Martha Faustena, who

she called Faustena. The girls all loved

and tended their baby sister.

Cousin

Charlie, who had been a baby when Gram

brought him from Massachusetts, and ten

years older than Hazel, developed

tuberculosis. He told Gram that he had

seen the leaves come out on the trees, but

he doubted if he would see them fall. He

died on 29 June 1910, three weeks after

Faustena’s birth.

Hazel

recalled the fire that burned their home

in 1914. Papa and May had taken a load of

barrels, which he had built in his cooper

shop, to Rockland. Four-year-old Faustena

had begged to go, but they had decided to

leave her at home with the other children

and Gram. She was very angry at being

left, and later told her siblings that she

was playing with matches, dropping them

down the cracks of the floor in the open

chamber above the kitchen. The house

caught fire, and in spite of the efforts

of the neighborhood men, the house burned.

Hazel recalled the shouting, pulling

barrels from the shop across the road,

throwing dishes and household items into

them and throwing them out the windows.

They brought buckets, and formed a bucket

brigade, but the fire was too far advanced

for the small amount of water to do much

good. Not much of the house and contents

survived.

The neighbors

brought their horses and oxen, hooked onto

the shed, which joined the house to the

barn, and pulled the shed out. In doing

so, they saved the barn. Father, with the

help of his neighbors rebuilt the house

and shed.

Most of the

family became members of Mystic Grange

down on the Back Belmont road. Centre

Belmont was a close-knit community where

everyone knew everyone else, and many of

the neighbors were relatives. The Grange

was the hub of activity, where the

neighbors came together, at least monthly,

sometime more often, for pot-luck suppers,

meetings and entertainment, of which they

were often a part of. The fellow-grangers

were among the first to come out if there

was a need amongst their neighbors. They

helped Father in the rebuilding of their

home.

May had

developed tuberculosis, sleeping on the

porch, as it was believed at the time that

the cold air was beneficial. Hazel spent

many hours with May, talking, reading to

her, and trying to cheer her. May died in

June 1917, just ten years after Mamma’s

death. May was twenty-three years old,

leaving seven-year old Faustena

motherless.

Bertha,

Hazel, and the many household siblings and

cousins each had to find work, to support

themselves, after finishing school at

Greer’s corner. They did housework for

others, and whatever work was available.

The boys worked in the woods, and in the

sawmill of Horace Chenery of Belmont.

Bertha had worked for Dr. Simmons in

Searsmont, and lastly working at a

restaurant in Belfast.

In 1918 the

influenza epidemic was raging, taking it’s

toll. It hit home when sister Bertha

became sick, coming home for Gram to take

care of. Hazel lovingly tended her sister,

but Bertha died in November of that year,

a victim of the epidemic.

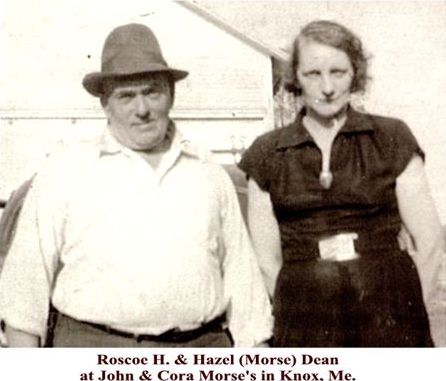

About that

time, debonair Roscoe Hurd Dean of

Northport, called Ross, came to work in

the Chenery sawmill with the Morse boys.

Hazel met him when her brothers brought

him home.

Ross had a

new car, and quite handsome Ross, with his

parents, Leslie and Lydia Dean, had lived

next door to Lydia’s parents, J. R. &

Eliza Hurd, on what was known as the

Knowles farm. When Lydia became ill, Lydia

and Ross moved in with her parents, who

took care of her. Lydia died, following a

lengthy illness in 1909, when Ross was ten

years old. He was raised by his

grandparents, elderly John Roscoe Hurd and

his wife, Eliza of Northport. Ross’ home

life differed from Hazel’s in that he was

the only child of an only child. Lydia and

her mother, Eliza, had both been

schoolteachers. Ross had attended the

one-room Brainard School in his

neighborhood. His teacher, Miss Alice

Pitcher, also a relative and neighbor,

said that Roscoe Dean was the smartest

pupil that she had ever taught.

Ross’ father,

Leslie Dean, had moved to Rockport. After

finishing the eighth grade at Brainard

School, Ross went to live with his father,

graduating from Rockport High School in

1917.

Ross began

courting Hazel. On the nineteenth of

August 1918, Ross and Hazel drove to

Bangor where they were married. They went

home to live with his grandparents, J. R.

and Eliza Hurd.

While Hazel

was in a family way she took care of

ailing Grandma Eliza Hurd, who suffered

long with kidney disease. Grandma Hurd

died April 5, 1919 at their home, aged

seventy-six. Three weeks later, Earl Hurd

Dean was born. They lived on with Grandpa

Hurd, though they spent some winters in

woods camps while Ross worked in the

woods. In the next years, Kenneth Roscoe

and John Leslie were born at the Hurd

farm.

Hazel

recalled visiting at Aunt Ada’s home with

Ross and the boys in their new car. Ross

took Ada, Dudley and Susie for a ride to

Searsmont village on an outing, leaving

Hazel to tend to the young boys.

On a cold

snowy Spring day in 1924, Gram Morse died

at Aunt Etta’s. Whatever had happened in

life, Gram was always been the steady rock

in Hazel’s life. Now, Gram, too, was gone.

Grampa John

Roscoe Hurd died in 1927, aged eighty-six,

leaving the farm in Northport to Ross and

Hazel.

Hazel was

expecting her fourth child. In June 1928,

Ross’ horse died. That may not have been

the most important thing in their lives,

but a week after the horse died, Hazel

lost her baby due to a premature birth. It

seemed that her world was crashing in on

her.

There had

been tremendous losses during Hazel’s

lifetime, and there seemed no way to cope

with them anymore. Early one morning she

went for a long walk in the woods. She

could hear the voices of family back at

the house calling her name, but the voices

in her head of all those who had gone

before were calling her deeper into the

woods. She was seeking someone who could

offer some comfort and rest. Hazel was not

aware at the time of the turmoil that her

young sons felt when their mother could

not be found. They were staying at

Susie’s, waking early in the morning to an

empty house with their mother gone and the

family out searching for her. Earl was

nine years old, Kenneth, aged eight, with

baby John barely three years old. John was

crying for his mother, while Earl tried to

console him, find him something to eat,

and change his clothes.

Two weeks

later, Susie went to Uncle Ed Howard, a

selectman of the Town of Belmont, who gave

an order to take Hazel to the big hospital

on the hill in Bangor.

Hazel’s

memory at this point was hazy. The time

spent at the asylum could have been weeks,

months or a year. While Hazel was sick,

the boys were at Susie’s for a time, being

cared for by Faustena, Aunt Ada Howard and

Susie. Kenneth went to stay with Hazel’s

brother, Amon and Mary in East Searsmont.

Earl and Kenneth attended school with the

Buck boys, Wilbur and Arthur at the

Greer’s Corner School.

It was a time

of financial turmoil in most of America.

Ross was having some financial

difficulties about this time. He sold

Grampa Hurd’s farm on the Belfast road

where he was born and always lived to

Hazel’s brother, Amon Morse. They then

purchased the Brainard farm across from

the Brainard school, about a mile from the

Hurd farm.

In 1930,

Hazel gave birth to her first daughter,

Bertha, who was the same age as Amon’s

daughter, Janette. The two girls were

close cousins. Earl went to live with his

grandfather, Leslie Deane, in Rockport to

attend high school as his father had

before him. Hazel wrote him letters,

informing him of family happenings. Earl

graduated from Rockport High School in

1936.

In 1938,

Barbara Carol, the youngest of Ross and

Hazel’s children was born. Barbara was

their baby, and the apple of the family’s

eye.

Hazel’s

kitchen in the old house, typical of the

times, had an old black cast-iron sink,

with a hand-pump which froze in the

winter, having to be thawed and primed

with water heated on the Home Comfort cook

stove. The sink drain which went out the

side of the house, also had to be thawed.

The home-made pantry cupboards had shelves

and drawers, across one end of the

kitchen. The house was unfinished

upstairs, making it very cold in the

winter.

Ross had

worked as a woodsman, as well as being a

trucker for a company in Belfast that sold

Home Comfort stoves. One winter Saturday

he was sent out to repossess a stove. His

employer told him that he would not have

his week’s pay until the next week, but he

could keep the gray-enameled stove with

warming ovens at the top as his pay if he

so wished.

Hazel hummed

as she worked in her kitchen, rolling out

biscuits, cookies, making gingerbread and

getting meals. Try as she could, her

biscuits never seemed to measure up to her

sister’s. Perhaps one reason was that

Ross, as a woodsman, sold firewood, which

was their livelihood, the customers

getting wood first. Hazel would keep fires

burning with whatever wood was in the

shed. She would often send Barbara and her

nieces out to the shed to ‘pick up chips’

to get the fire hotter.

All the while

the neighborhood children ran in and out,

pestering her for gingerbread or whatever

she had. They thought that she never knew

that they chewed the gingerbread, spitting

it out, mimicking Ross chewing tobacco.

Her

neighboring nieces, Isabel, Annie and

Sylvia spent many, many happy hours in her

home with Barbara. Hazel told them stories

of her growing-up years, about the

grandmother who raised her, and tales

about the War effort of World War II as

they bounced on the bed behind her as she

sewed at her treadle sewing machine. They

were usually too busy being children to

take note of the tales that she told them.

Hazel lived

when food staples, flour and crackers were

bought by the barrel, molasses was bought

by the gallon, pumped from a molasses

barrel at a country store, and most of the

vegetables were raised on the farm. The

apple trees provided fruit for the winter,

as well as for pies. They raised a hog for

the cooking lard, and meat, and kept

cattle for milk. Most of the neighboring

farms at the time were self-sufficient,

supplemented by the meat from venison,

rabbits, wild game which the boys

regularly brought in. .

She was

frugal, versatile, and resourceful raising

her family of hungry boys and family. She

made heavy quilts with dyed white flour

sacks for the backing, using printed grain

sacks for quilt pieces. She made striped

cotton ticking featherbeds, and mattresses

stuffed with straw, renewing each year.

She heated bricks on the wood stove,

wrapped in flannel to keep the family’s

feet warm at night. She made tiny

professional-looking doll clothes for

Bertha and Barbara and later for her

grandchildren.

During World

War II, Hazel’s sons, Earl and John went

into the Armed Forces to serve in the War.

Earl serving in the Army Air Force, was

sent to the South Pacific. John served in

the U. S. Army was sent to Germany, where

he was wounded, receiving a Purple Heart.

A mother’s heart breaks while her sons are

far away, not knowing if they are hurt or

even alive. Hazel proudly hung her Service

stars in the front window until the boys

came safely home.

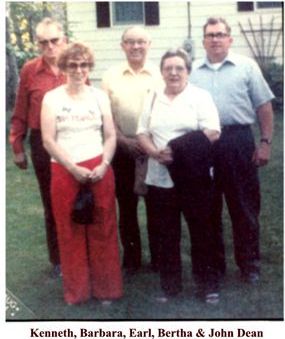

The children

married, raising families of their own.

Earl lived in Camden with his wife, Dolly

and six children. Kenneth lived nearby

with his wife, Ella and son Jimmy. Bertha

lived nearby with her husband Bob, raising

seven children. Barbara married Pete

Reilly, who was in the Air Force. They,

with their two sons, moved around the

country. John brought his wife, Marilyn,

home to live with Hazel and Ross in 1949.

They had seven children, the first,

Johnny, died in 1953, aged one year, and

six-year-old daughter Katherine, later

died in a tragic automobile accident in

front of the house.

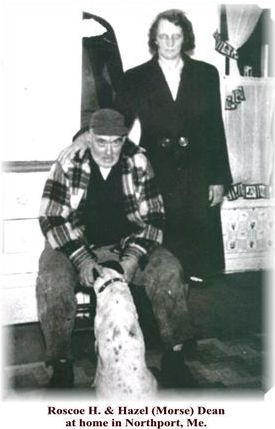

Ross, the

love of Hazel’s life, suffered a massive

stroke at their home in 1955. He was taken

to Waldo County Hospital where he died,

aged fifty-six years old.

Hazel loved

to hear the grandchildren and their

friends playing and laughing in their

home. When she became tired, she could go

into the bedroom off the kitchen that she

shared with Ross for many years, enjoying

the quiet.

Now, at the

age of seventy-two, in her bed in Waldo

County Hospital in Belfast, she recognized

the voices of those that she had dearly

loved, welcoming her into the realm that

mortal man cannot see. Peace filled the

room at the hospital as Hazel Ada (Morse)

Dean entered into the Kingdom of Heaven.

|

.jpg)