It was cold in the old

house on the Plains Road in Montville,

Maine. Martin couldn’t get out of bed

anymore. There was no heat in the old

house, as he couldn’t get up to wood the

fire in the kitchen stove. Dell was

working at a neighboring farm, or so

Martin thought. Robbie was in school. The

boys tended out on him as best they knew

how. Neighbor Maria Griffin checked in now

and then, bringing him hot soup.

Martin missed

Melinda, the wife of his youth. She had

been gone nearly eighteen years now.

Memories flooded, as he bore the pain of

the old War wounds. Seemed like things had

gotten much worse lately. Perhaps it was

the chill of winter coming on. He dreaded

the cold and loneliness of the coming

winter.

Martin missed

Melinda, the wife of his youth. She had

been gone nearly eighteen years now.

Memories flooded, as he bore the pain of

the old War wounds. Seemed like things had

gotten much worse lately. Perhaps it was

the chill of winter coming on. He dreaded

the cold and loneliness of the coming

winter.

Mart, as Melinda and his

family fondly called him, recalled that

hot July day in 1862, actually the last

day of the month, that he had arrived at

the farm of Levi Bartlett on the other end

of Montville, near the Freedom town line,

and next-door to old Mr. Whitten. Mart and

his brother, Horace Hannan, had walked,

catching a ride part way on the back of a

wagon, from South Liberty to the farm to

help with the haying. They would be

staying with the Bartlett family 'til the

loose hay was all in the barn.

That morning they started

mowing the field on the lower side of the

road. Swish, swish, swish, was the sound

of the hand-scythes as Levi stepped into

the field, cutting a swath, followed by

Mart, who in turn was followed by Horace,

then by three farm hands. Swish, swish,

swish, as the men kept in rhythm across

the hay field. It was hot, as Mart

recalled, but he would soon experience

heat much hotter than any heat he’d felt

on a hot Maine summer day.

As they mowed back across

the field after several swaths, a man rode

up on a sleek black horse. Levi yelled,

asking the man what his business was.

After asking the sweaty workmen if they

were aware of the bloody battle of the

previous year at Bull Run, in which nearly

three thousand of the Northern soldiers

had been killed, wounded, or just plain

missing, he identified himself as a

Recruiter for President Abraham Lincoln,

who was asking for volunteers to sign on

to fight the menacing Southern Army of

General and President of the Confederacy,

Robert E. Lee.

Mart recalled that after

the Recruiter left, Levi and the farm help

went back to their task of mowing the

field, swish, swish, swish. Mart was a

strong young man of twenty-two years, able

to keep up the hardiest of his friends and

neighbors, and able to do a long, hard

day’s work. The words brought by the

passing messenger echoed in his ears. It

shouldn’t take long to whip the Rebels,

and keep the country strong and secure.

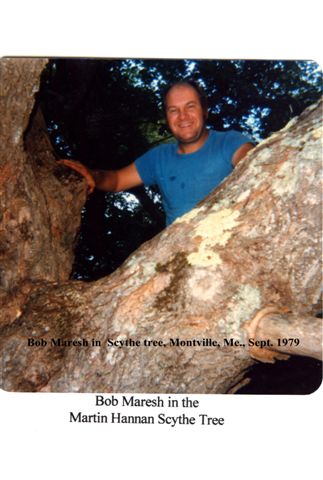

Levi’s daughter

yelled across the field that it was time

for dinner as they arrived back by the

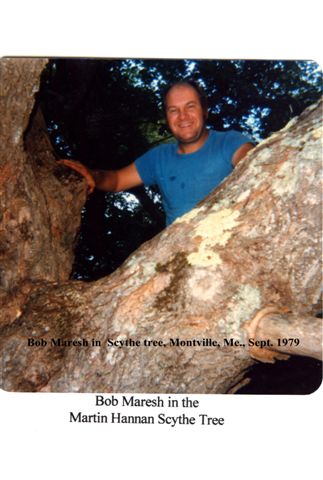

roadside. Mart hung his scythe in a young

sapling maple tree, as the men went back

to the farmhouse to eat dinner. He didn’t

have much to say that day. He pushed back

his plate and chair after eating the

hearty dinner prepared by Ann Bartlett and

her daughter, Ann, and reached for his

straw hat. “I’ll finish the field when I

get back,” he told them. “I’m going after

that Recruiter!” As he started down the

road, he heard Horace yell, “Wait up. I’m

going with you!”

Levi’s daughter

yelled across the field that it was time

for dinner as they arrived back by the

roadside. Mart hung his scythe in a young

sapling maple tree, as the men went back

to the farmhouse to eat dinner. He didn’t

have much to say that day. He pushed back

his plate and chair after eating the

hearty dinner prepared by Ann Bartlett and

her daughter, Ann, and reached for his

straw hat. “I’ll finish the field when I

get back,” he told them. “I’m going after

that Recruiter!” As he started down the

road, he heard Horace yell, “Wait up. I’m

going with you!”

Mart and Horace returned

home to South Liberty to tell their family

of their decision. They had a month to get

their affairs in order. There was a

beautiful young seventeen-year-old girl

over on the New England Road in Searsmont

that Mart wanted to speak to before

he left.

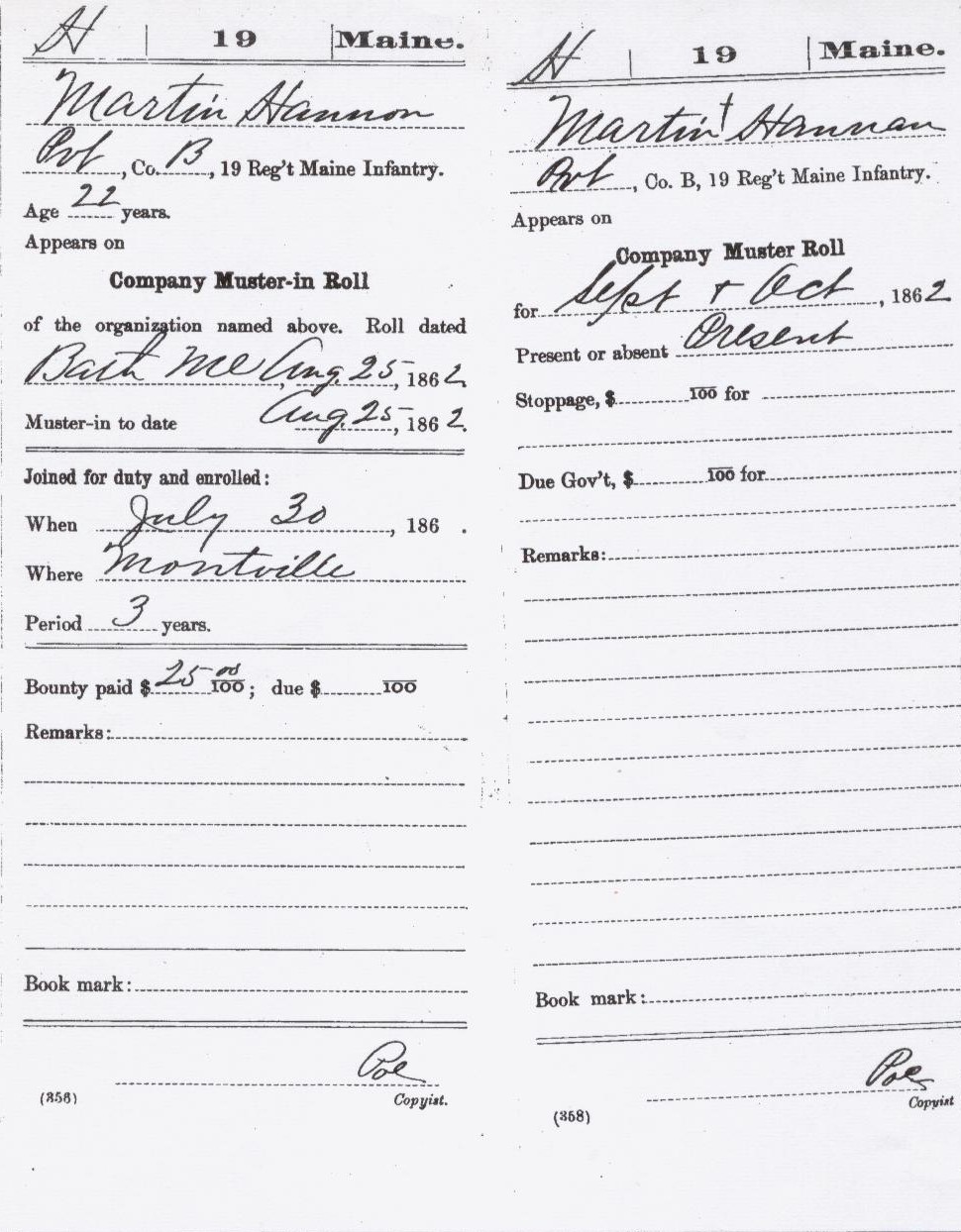

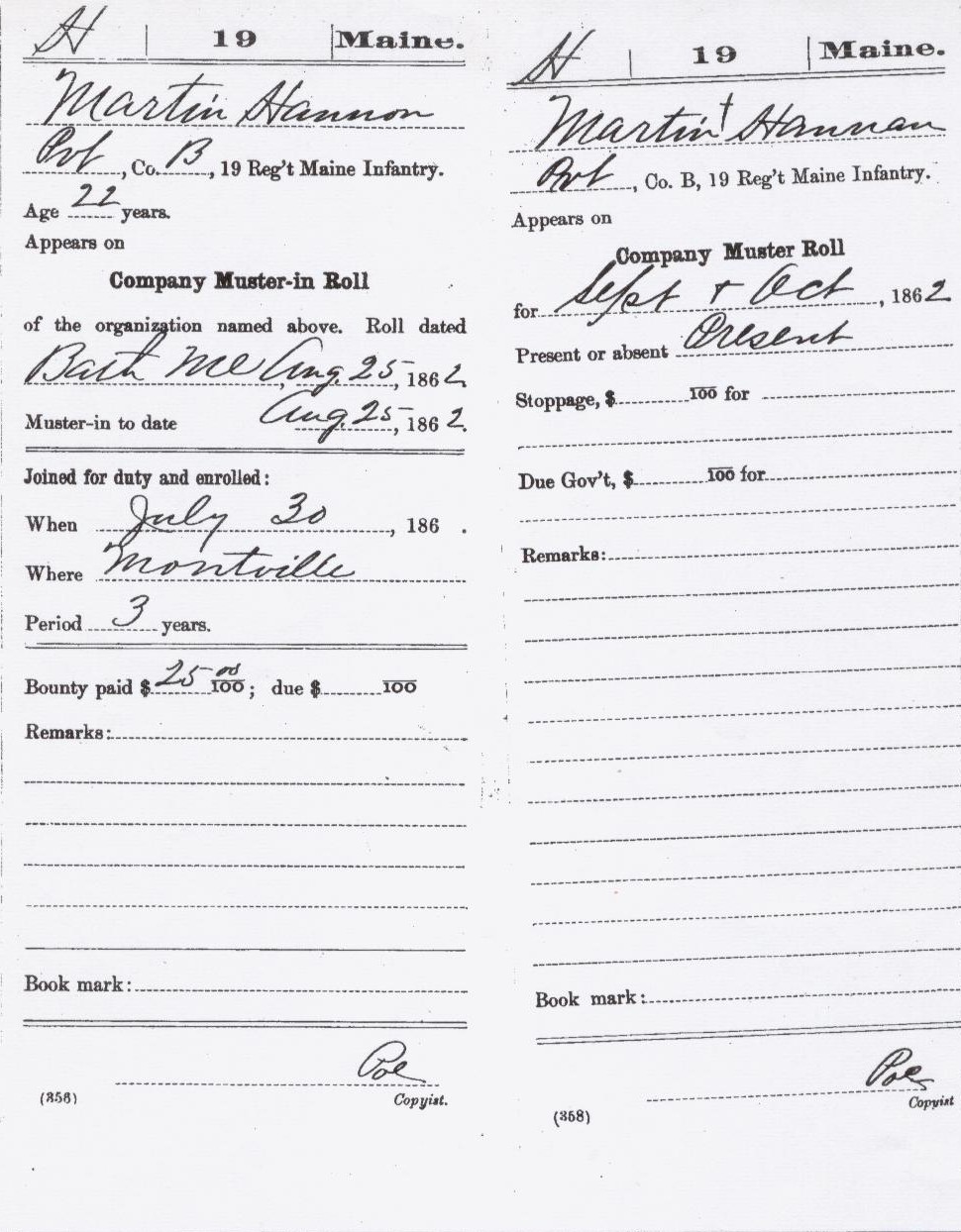

Mart winced at his pain

and the cold, as memories of what that

decision had had on his life. He and

Horace went to Bath, Maine, along with

some of the other men and boys of the

community, many of them he knew from

Montville, Liberty, Palermo, Searsmont,

and other local towns, to be mustered into

the service for three years. There they

received a royal-blue uniform and cap, a

brown woolen Army blanket, and a pair of

ill-fitting shoes. They left Bath by

train, into an unknown land, with unknown

battles to be fought. At Bath they were

paid a $25 bounty, after they were sworn

into Company B of the Nineteenth

Regiment of the Maine Volunteers. “What

were we thinking?”, Mart mused. From that

day in August, 1862 in Bath, when they

were mustered into the Union Army, life as

they knew it changed forever.

They first arrived by

train in Washington, D. C. From then on,

they marched. It seemed that it was always

hot. It rained a lot also, as they trudged

through mud, sometimes nearly up to their

knees. Their meals were mostly hard bread

and beef, with strong hot tea. Drills were

held, again and again. The enemy was

everywhere. It was hard to tell who was

friend and who was foe. The only

difference was the color of their uniform,

and once they were all dirty and dusty, it

was even harder to see a difference.

Mart’s memories were

vividly real to him, as he tried to get

comfortable in the cold old house. As

vividly as when he swore out an affidavit,

while applying for a pension, about the

injuries that he’d received in Dec., 1862.

He had been detailed to Hazard’s Battery.

At Bell Plains, Virginia, they were

building a ‘corduroy’ road just before the

Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia. He and

three comrades were carrying a large log

to put into the road. The ground was very

rough. Mart winced as he remembered

stepping into a hole, and felt the severe

pain through his lower stomach and groin

area. Doctor Billings told him that he had

ruptured his groin area and his testicles.

The War ground on. Some

of the men had come down with measles. No

one would have thought that a childhood

disease like measles, would kill grown

men, but several men had perished as the

result of contracting the measles. Mart

had heard of another Company having the

threat of a smallpox outbreak.

In March of 1863, some of

the officers felt that Mart had leadership

qualities and promoted him to Captain.

He’d made some good friends, a few who had

left home with him, among whom were John

M. Wellington, Orrin Overlock, Edward

Mitchell, Stephen Daggett, Benjamin

Crooker, and Israel H. Cross, and oh, so

many other comrades. There were some good

times with the comrades, but it was hard

to recall them now. They’d play cards at

night, if they were not too tired, and it

was a time to write home, if one had

paper, a pen, and a stamp. Ink was hard to

come by, and a letter written in ink could

easily be smudged if the rain got on it.

If someone had a musical instrument, the

mournful sound carried throughout the

camp.

In the middle of June,

1863, while they were marching from

Falmouth and Fredericksburg, Virginia, at

a place called Dumfree, Virginia, it had

been a very hot day, so hot that Mart felt

that he couldn’t go on. The next thing he

remembered, he woke up, looking up at the

hot sun, now knowing how long he’d been

unconscious. He crawled under some bushes

by the side of the road. That day about a

dozen of his comrades had been stricken by

the heat. Brother Horace and Bill

Churchill were also on the march that day.

Israel Cross, the comrade from

Lincolnville, stayed with Mart til

nightfall, which brought a little relief.

The soldiers brought the stricken men into

camp late at night in an Army hospital

wagon. Dr. Billings tended to him, and

other fallen soldiers. The next night Mart

and Israel caught up with the Regiment.

Some men were not so lucky, and completely

heat-struck.

On and on throughout the

country they marched. It was always hot.

In July, 1863, they’d marched to

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Mart had never

seen so many men in one place, lined up on

opposite knolls. Then all hell broke

loose. Men fell on the left, on the right,

in front and behind him. He could hear

screams, yelling and moans of the wounded

and dying. There was no time to even think

of his younger brother, Horace. Then he

felt the hit. He’d been struck by a shell

fragment in his left hip. It broke the

skin, but he was so much better off than

many around him. He did not complain. That

night his comrades convinced him to tell

the Regiment surgeon, Doctor Billings, who

dressed the wound and applied a plaster.

But the darn thing wouldn’t stay on, and

chaffed it even more. He threw the plaster

by the roadside. But, yes sir, he was back

in action the very next day. In September,

1863, he was once again promoted, this

time to Sergeant.

In January, 1864, Major

Rollins and Captain McDonald, the

commanders of the Invalid Corps ordered

Mart to Camp Berry in Portland, Maine as a

Recruiter. He wondered if he should have

tried to convince others to go through

what he had been through. But that old War

couldn’t last forever. He was allowed a

furlough to go home. The cold Maine winter

seemed pretty darn good to him, after the

extreme heat of the South.

While home on a furlough,

Mart went to Searsmont to see pretty

Melinda Herrick, who lived with her

parents, Andrew and Betsey Herrick on the

New England Road. Mart and Melinda were

married in Montville on

February twenty-first, 1864, by Rev.

Moses McFarland. They intended

to spend the rest of their lives

together. Mart returned to Portland, where

he was Recruiting officer til January,

1864, when he returned to his Regiment. He

received an honorable discharge from the

Army at Bailey’s Crossing, Virginia on

the thirty-first of May, 1865. Nearly

three years in the service of the Union,

and he had the scars and pain to show for

his service time. Mart recalled that he

felt as though he’d been through the fires

and trials that the ministers preached

about in the Sunday services that the

servicemen had attended.

Mart returned to South

Liberty, where he purchased the

seventy-acre farm that had belonged to old

Robert Lermond, who had died in 1860,

bordering on the farm of his parents, John

C. and Julia Hannan. The farmhouse had

been vacant for some time. Robert

Lermond’s son, John, who lived over in the

Fishtown section of Appleton, had

purchased the farm from the heirs. Mart

and Melinda had moved onto the farm

shortly after their marriage. He’d gotten

the farm paid off in 1870, receiving the

deed at that time from Lermond.

Mart and Melinda settled

down to raise a family on the farm. Their

firstborn, Charley was born in 1866,

followed by Annie, Addie, Herbert, Rose,

as pretty as her name, Odell, named for

Mart’s grandfather, John Odell Hannan,

Carrie, who he fondly called ‘Cad’, Ella,

and the baby, Robbie, born after moving up

to the Plains, in 1885.

Mart did some farming,

and coopering in his shop, where he made

barrels, called casks, for the lime

industry in Rockland. He’d harness up the

horse, load the hay wagon with casks,

drive through Fishtown and Burkettville,

to Union, down through Rockport, on to

Rockland. The casks did not bring in much

money, but the work was light, and could

be done on rainy days and early evenings

in the summer, as well as the cold snowy

days in the winter in his cooper shop

where he kept a wood fire to take off the

chill. On the way home from Rockland,

after delivering the barrels to the lime

industry, he would pick up staples by the

barrel, gallon or sack, such as flour,

crackers, molasses, etc., and a little

treat for the young ones, if the load had

been profitable at all.

Since his discharge from

the Army, Mart had suffered from heart

palpations, dizziness and even fainting

spells. One day he passed out while

working on the farm. His brother Bill

happened along, thinking that Mart was

dead, quickly went for their parents, John

C. and Julia Hannan. Dr. Young was called,

and admonished Mart to keep out of the

sun. The doctor had considered that it was

probably from the heatstroke suffered in

the South. Any exertion brought on

dizzy spells. The War wound and rupture

were a constant source of pain. He

sometimes told of troubles in his head.

Mart applied for a

Government Pension. James Fish who had

known Mart since he was a young child,

testified by affidavit as to how rugged a

man Mart had been before he went to War.

His War comrades, Edwin S. Mitchell, who

had once been a tent mate, testified that

he saw Mart fall under the weight of the

log in the Army at Bell Plains. Another

old tent mate, Israel H. Cross of

Lincolnville, testified by affidavit of

watching over Mart when he was unconscious

over half a day with sun stroke. After

returning home, Mart had been treated by

Dr. Young, who had died in 1875, then

by Dr. B. H. Bacheldor of Montville,

until his death in 1889, and

later treated by Dr. E. L. Porter of

Liberty.

As Mart signed his name,

Martin Hannan, on affidavit after

affidavit, he recalled that he had been

named for his grandfather, Martin

Overlock, a descendant of the hardy German

immigrants who had come to Old Broad Bay,

later called Waldoboro, from Germany, many

years before settling in South Liberty.

The elder Martin lived to a ripe old age.

Mart’s neighbor, Hathorne

Brawn, who later married his daughter,

Annie, testified by affidavit that Mart

was often struck by nervousness and

prostration, and would suffer from

coldness even on a hot day. George Smith,

a near neighbor for about ten years,

testified by affidavit in 1893 that Mart

suffered from shortness of breath, and

could not do hard labor. Mart received a

Pension of $4 a month, eventually

increased to $8 a month for the rest of

his life.

Mart and Melinda were

doing fairly well on the farm in South

Liberty. In Mart’s eyes, she was a

beautiful girl. She kept the children fed

and clean, scrubbing their clothes on a

washboard, carrying water from the well

for the household, as well as helping him

with the little garden that they grew. She

canned and salted down the vegetables for

their winter larder. He had a cow, a

horse, and annually raised a pig for their

table use. He and Melinda salted down the

pork for use in baking Saturday night

baked beans, and for ‘trying’ out each day

to eat on the potatoes and vegetables that

they raised in the garden. It seemed to

him that Melinda worked a little harder

than a lot of the neighbor women, because

of the fact that he was just not able to

do what he’d liked to have done. Some days

it was just hard breathing. Melinda and

young Herbert would do the farm work, as

well as keeping the family together. Mart

had taught Herbert to shoot. They both

were quite lucky hunters, bringing in

venison and rabbits to supplement the

family larder.

Melinda’s sister, Olive

Robinson, lived way Down East. She and

Melinda kept in touch by letters. Shortly

before Robbie birth, Melinda wrote to

Olive, telling her that Mart had finally

gotten his Pension, and that Charley would

be bringing her down to visit one of these

days.

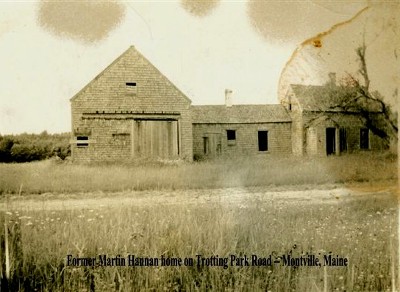

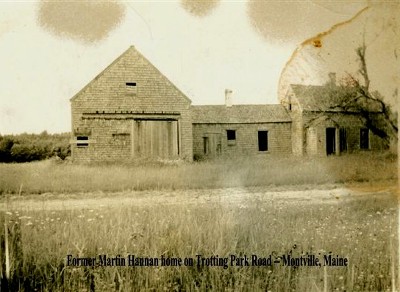

Mart and Melinda, with

their growing family, had moved from his

father’s neighborhood in South Liberty in

the fall of 1884, to a farmhouse with

twenty acres, more or less, on the Plains

Road in Montville. He had purchased the

farm from his Aunt Sarah Hannan for $125.

They had moved into the farmhouse, giving

Aunt Sarah payments, such as he could,

with the boys’ help, until the place was

paid off.

It was five and half

weeks after baby Robbie was born, and

Melinda still had not rallied. It was her

eighth child, a difficult birth, and she

was sinking fast. Melinda’s mother had

died a year after their marriage. Her

father, Andrew, had hung himself during a

time of depression in April of the

previous year. Martin’s mother, Julie,

passed away on the nineteenth of

February, 1885, so there was no one in the

family to come to their assistance. Their

girls did what they could, and tended out

on the younger children, getting meals,

and generally keeping house. Melinda died

on Wednesday, the twenty-second of

April 1885. She was only forty years old.

He laid her to rest beside her parents in

the Village Cemetery in Searsmont. There

was a small wooden marker to mark her

gravesite, with no stone to mark his

in-laws’ graves. He planned to buy Melinda

a fancy headstone, but the little wooden

marker would have to do for the time

being.

On the very day that

Melinda died, Aunt Sarah had signed the

papers deeding the property to Mart. It

was to be the home that Mart and Melinda

would farm and live to old age together.

After Melinda’s death,

with an infant to take care of, living on

the Plains Road, Mart struggled to keep

his family together. The girls helped care

for little Robbie. Annie had married a

month before Melinda’s death, at age

seventeen, to Hawthorn Brawn, and lived

nearby. Addie, who a lot of people called

Jennie, was age fifteen, when she married

Daniel Linscott six months after Melinda’s

death. Daniel was nine years older than

Addie. In spite of rumors, Mart

hoped that Daniel would be good to his

daughter.

Herbert was but twelve

years old when his mother died. He’d

always been a help to Mart, even when he

was a small child. He seemed to sense that

his father was not well. Because Mart was

not well enough to do hard labor, he had a

lot of time to watch over little Robbie.

When Melinda died, Charley was nineteen, a

year older than Horace had been when they

joined the Army. Charles was out on his

own, working at local farms. Rose was

eleven years old, Odell was nine, Cad,

nearly six, Ella was four years old, and

baby Robert was just a tiny infant of a

little over a month old. Mart had always

been so good at remembering his children’s

birth dates, but he was getting a little

forgetful. Who could blame him?

Mart remember the fateful

day in 1891, when ten-year old Ella, a

beautiful fair-skinned child, who looked

so much like her mother, fell out of the

old apple tree while playing with Cad. She

struck on her head and neck, and almost

immediately perished. There was no room to

bury Ella with her mother, so Mart had

purchased a cemetery plot in Searsmont, in

the Pine Grove Cemetery, near the South

Montville Town line. Two lives cut short

in a brief span of time, in the prime of

their lives, taking a piece of Mart’s

heart with them. How he missed them both.

Someday he’d move Melinda’s remains there

to be interred next to Ella, and he when

his time came..

Mart’s father, John Colby

Hannan, who had also served in the Civil

War, died on the fifteenth of August

1901. He was 82 years old. John had not

served in the same Regiment as Mart,

Horace, and later William. When talking

about their War experiences, John had told

Mart on more than one occasion, how hard

it had been for an older man to keep up

with the younger soldiers.

So many of those closest

to Mart had gone on before him. Mart

attempted to shift over in his bed, though

he could not move much because of the

pain. He was trying to keep warm. It was

now November, 1903. Winter seemed to

coming in early, or perhaps it was just

his old bones that thought that it was

colder than usual. Perhaps Maria would

bring in some hot soup or oatmeal this

morning. Hark! Did his ears deceive him,

or did he hear sleigh bells? Someone was

at the door. “Maria?”, he called. It was

not Maria, but Herbert coming to check on

him. Behind him followed Cad, and Dell.

Dell had not gone to work, but had gone

for Herbert and Cad instead.

Cad had her own problems.

She had married the mail carrier, Charles

Marden, when she was eighteen. Little

Delbert, her first-born son had drowned in

the mill pond two months ago. He was a

month shy of being 5 years old.

“What’s that you say,

Cad? It’s colder in here than outside. I

just can’t get out of bed to wood the

fires.” “What’s that, you say, Herbert?

You’re taking me home with you.”

Cad put Mart’s old

royal-blue Army coat with the brass

military buttons onto him. Today it would

nearly go around him twice. “My, Papa,

you’ve lost weight”, Cad said. He supposed

that he had. When he entered the Army,

they weighed and measured him at Bath. He

was five feet, nine and a half inches

tall, and weighed a good sum. They

recorded that he had a light complexion,

dark eyes and brown hair. What hair he had

left was totally white. Melinda always

said that he had “pretty blue eyes”. Yes,

he was sure that he probably had lost some

weight, and was but a shadow of the man

that he had been, when he left the

hayfield in the prime of his life, to go

to War. He recalled that day, when he had

hung the scythe in the crotch of the

sapling maple. He had fully intended to

come back and finish up the haying, but it

wasn’t meant to be. He’d met Levi Bartlett

a few years back. Levi told him that the

tree had grown around the scythe, and he

had left it as a testimony to the young

man who’d gone off the fight the Rebels.

His mind snapped back to

the present. Herbert and Dell got Martin

onto a home-made stretcher. Cad and Dell

were wrapping his old brown woolen Army

blanket around him. He recalled the many

nights in the South, when he slept with

the old blanket on the cold ground. But,

that was in the past.

Mart’s two sons gently

carried their father out to the waiting

horse and loaded him onto the pung, with

Cad riding on the back with him. They then

drove the horse across the Plains Road to

Ben Boynton’s farm in the Kingdom, where

Herbert’s wife [and Ben’s daughter]

Millie, and children were waiting in the

warm old farmhouse kitchen. A bed had been

prepared for Mart in the front parlor

where a fire was burning brightly in the

parlor stove. Mart was warmly and lovingly

tucked into bed. As they took off the blue

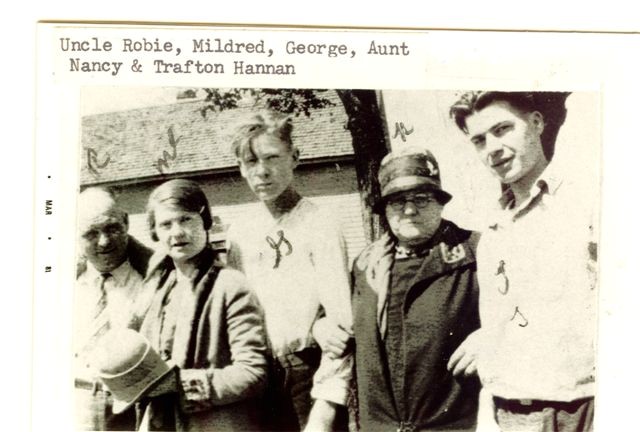

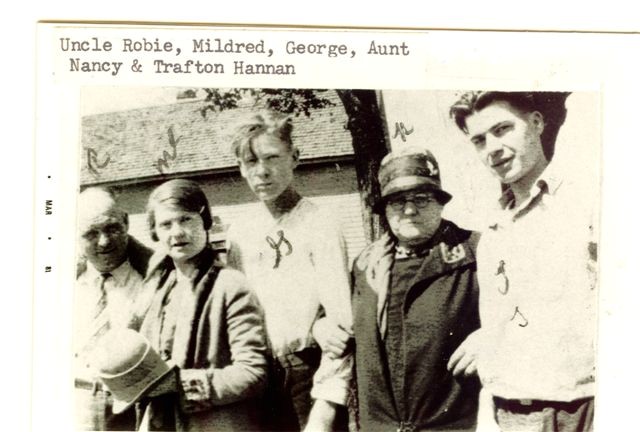

Army coat, four-year old Mildred, and

Gladys, not quite two years old, rubbed

the soft wool of the coat, while Herbert,

Jr., aged a year and a half, was

fascinated by the shiny brass buttons.

Mart told Cad to give the coat to Mille to

make warm outerwear for the little ones.

He said, “I probably will have no more use

of it now!”

Millie brought Mart some

venison stew and hot “slut” biscuits with

home-made butter. Herbert brought him a

glass of cold raw milk, which tasted so

good. Old Ben Boynton welcomed Mart to

their home. The young ones roamed in and

out of the room, chatting to him and each

other, seemingly happy to have him there.

Mart enjoyed telling them stories of his

War years, reminding them that their

great-grandfather, John Colby Hannan, had

also served in the War, along with

great-uncles, Horace and William. Mart

knew that the children were too young to

understand all that he told them, but he

enjoyed their company.

Mart spent a pleasant

winter, though his body was wasting away

and racked with pain. Spring would soon

come, and perhaps some time outside would

be pleasant. He could dream of the warm

days. Dr. Albert D. Ramsay of Brooks came

to treat and medicate him, to try to make

him more comfortable from the chronic

inflammation of the old War wounds.

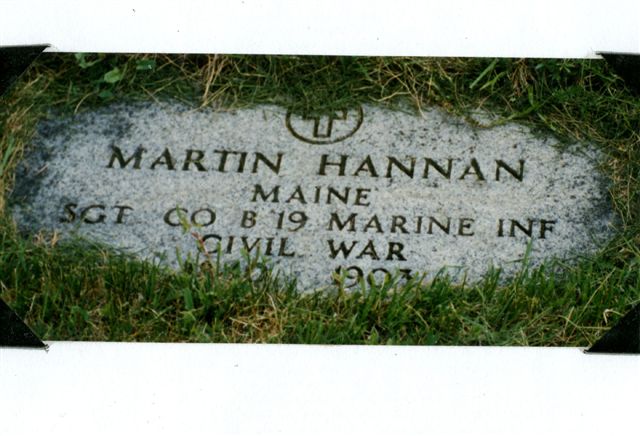

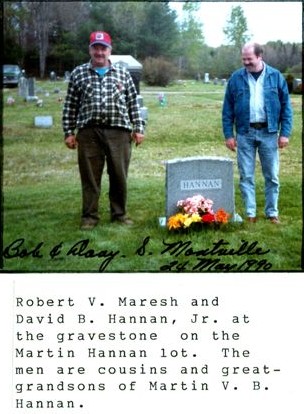

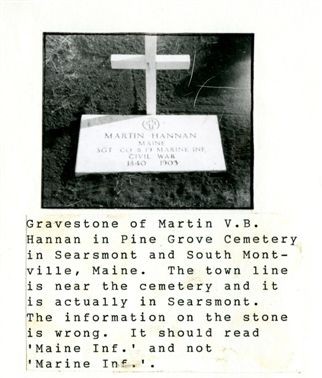

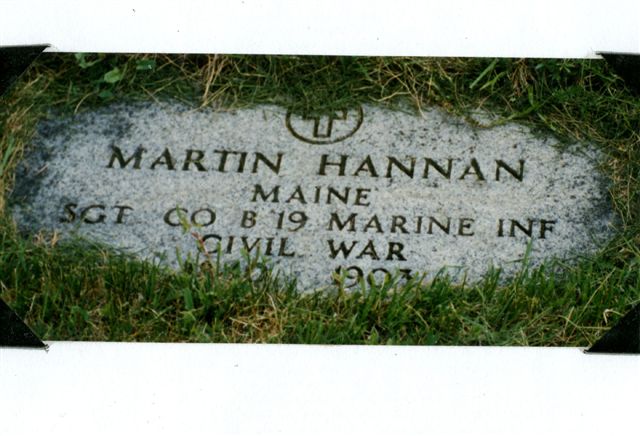

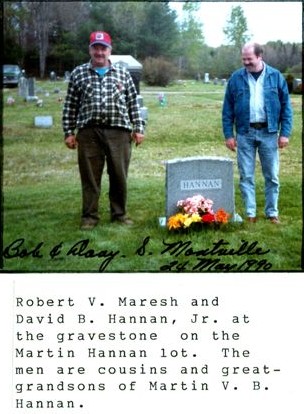

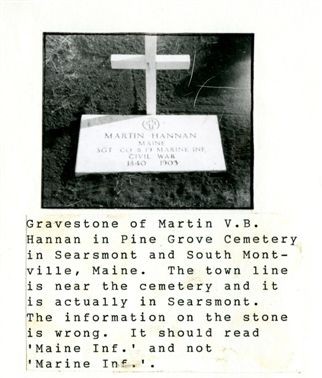

Martin Van Buren Hannan

died in the loving home of Herbert, Millie

and their young children on a warm Spring

day, on Sunday, April tenth, 1904. He

was but sixty-four years of age, but

had suffered much more than a man of his

years should have. He was laid to rest in

the Pine Grove Cemetery in Searsmont, with

little Ella. He’d never gotten around to

bringing Melinda’s remains to join him and

Ella. There was no gravestone to mark his

burial site, until many years later, when

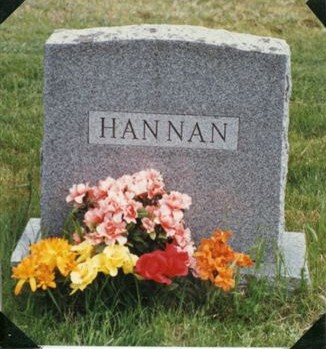

his descendants, Mildred, Gladys, Herbert

and David obtained a Government grave

marker and a simple gray granite monument

with “HANNAN” etched on it, as well as

grave markers for Herbert and

Millie.

[In 2006, great-granson,

Fred Bragdon, of Vassalboro, Maine, had

the Government gravestone for Martin

Hannan, in Pine Grove Cemetery, turned

over and engraved with the correct

data. The former gravestone had

'MARINE' engraved on it in error.

Fred had the etching changed to 'MAINE'.]

Martin missed

Melinda, the wife of his youth. She had

been gone nearly eighteen years now.

Memories flooded, as he bore the pain of

the old War wounds. Seemed like things had

gotten much worse lately. Perhaps it was

the chill of winter coming on. He dreaded

the cold and loneliness of the coming

winter.

Martin missed

Melinda, the wife of his youth. She had

been gone nearly eighteen years now.

Memories flooded, as he bore the pain of

the old War wounds. Seemed like things had

gotten much worse lately. Perhaps it was

the chill of winter coming on. He dreaded

the cold and loneliness of the coming

winter. Levi’s daughter

yelled across the field that it was time

for dinner as they arrived back by the

roadside. Mart hung his scythe in a young

sapling maple tree, as the men went back

to the farmhouse to eat dinner. He didn’t

have much to say that day. He pushed back

his plate and chair after eating the

hearty dinner prepared by Ann Bartlett and

her daughter, Ann, and reached for his

straw hat. “I’ll finish the field when I

get back,” he told them. “I’m going after

that Recruiter!” As he started down the

road, he heard Horace yell, “Wait up. I’m

going with you!”

Levi’s daughter

yelled across the field that it was time

for dinner as they arrived back by the

roadside. Mart hung his scythe in a young

sapling maple tree, as the men went back

to the farmhouse to eat dinner. He didn’t

have much to say that day. He pushed back

his plate and chair after eating the

hearty dinner prepared by Ann Bartlett and

her daughter, Ann, and reached for his

straw hat. “I’ll finish the field when I

get back,” he told them. “I’m going after

that Recruiter!” As he started down the

road, he heard Horace yell, “Wait up. I’m

going with you!”