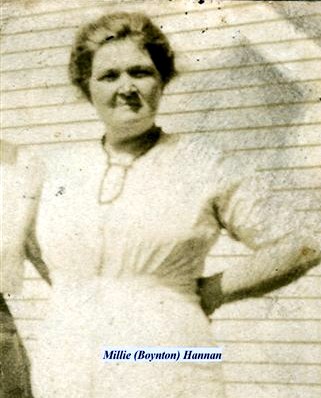

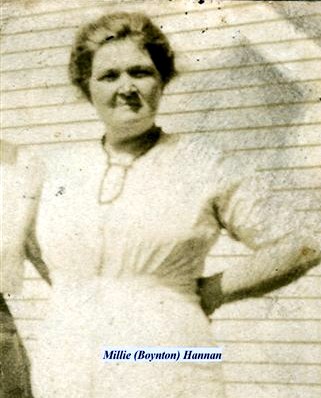

Millie Boynton

Hannan’s Eventful Life

Millie wiped her hands

on her apron. She would have wiped her

eyes, but she could not cry, nor shed a

single tear. She’d often cried at night,

but no one would ever see her cry.

She looked back over her

life. So much had happened in her

lifespan of thirty-three years. She

remembered her wedding day when she was

nineteen. Her mother had passed away in

June of that year, never knowing that

her youngest daughter was “in a family

way.” Mother had suffered a long time

with terrible pain due to stomach

cancer.

On Christmas eve in

1898, Mille had married Herbert Hannan,

six and a half years older than she. He

was a handsome young farmer whose father

and grandfather had served in the Civil

War. Herbert’s own mother,

Melinda, had died at age forty when

Herbert was but twelve years old. How

Millie missed having her mother to talk

with. Herbert had swept her off her feet

with his charming ways and flashing wry

smile. Just a twinkle in those sparkling

blue eyes of his would melt Millie‘s

heart.

Herbert was a hard

worker and provided well for her and

their growing family. But as more

children arrived, it seemed harder to

keep up with feeding and clothing the

brood. Mildred was born in 1899,

followed by Gladys in 1900. Then came

Herbert Jr., Roy, Bertha, Daisy, David,

Trafton, Waldo and Lester, all within

eleven short years.

Papa was a great help,

asking Herbert and Millie to move in

with him in his large farmhouse in the

Kingdom. Herbert and his brother, Dell

and sister, Cad had gone to the other

side of Montville on the Plains Road in

November 1903 and brought Hebert's

father, Civil War veteran and widower

Martin Hannan on a sleigh called a pung,

home to the Boynton farm to live with

them. Martin died in April 1904, age

sixty-four years of age.

Herbert worked out for

local farmers, as well as coopering at

home on the farm. His barrels were of

fine quality, which he hauled to

Rockland, through Searsmont, down over

Moody Mountain to the Bog Road, through

Camden with his horse pulling the old

hay wagon loaded with barrels, which

were termed ‘lime casks.’

He sometimes took young

Herbert and Roy with him. Even though

they were young, they were a great help

around the farm and in the cooper shop,

so much so that he often forgot Herbert

was only nine years old.

One

winter night in 1909 Herbert’s cow died.

The local newspaper under the South

Montville town column wrote: “Herbert

Hannan recently lost his only cow and as

he is a poor man, with quite a large

family, his kind neighbor Mr. Baker, has

started a subscription to get another

cow for him. We hope all who have the

opportunity and can help, will put their

hand down into their pocket. A friend in

need is a friend indeed.”

One

winter night in 1909 Herbert’s cow died.

The local newspaper under the South

Montville town column wrote: “Herbert

Hannan recently lost his only cow and as

he is a poor man, with quite a large

family, his kind neighbor Mr. Baker, has

started a subscription to get another

cow for him. We hope all who have the

opportunity and can help, will put their

hand down into their pocket. A friend in

need is a friend indeed.”

Millie worked hard

raising her children, breast-feeding as

long as she could, preparing meals,

canning, making butter and cheese,

salting down greens and salt pork,

washing their clothes on a scrub board,

drawing water from the well for cooking

and washing.

She made clothing for

her children whenever she could get

material. Her father-in-law, Martin gave

Millie his blue woolen Civil War coat

with brass military buttons on it.

Millie made a coat for Mildred from it.

Mildred wore the coat, Gladys wore it,

then Herbert. It was then given to a

poor neighbor boy to wear out. It was

hard to believe there were any poorer

children than Millie’s in the

neighborhood.

On another cold night in

January 1911, one of the family smelled

smoke. The fire in the stove had been

wooded to ward off the chill that crept

into the old farmhouse. A fire was

discovered in the living room, which had

started around the funnel of the

stovepipe which went into the chimney.

Embers had dropped onto clothing drying

on a rack behind the stove. Some of the

clothing and bedding burned, but the

family thought itself very blessed to

still have a roof on the house.

Millie remembered the

day Herbert came in from the cooper

shop, saying he couldn’t see well, and

that he had a blinding headache. He went

to bed, asking young Herbert to come sit

with him. He told the boy to take care

of his mother and to watch over the

younger siblings. The headache grew

worse. There was no money to call for

the doctor, but Papa sent young Herbert

to Liberty to fetch Dr. Albert D.

Ramsay. Herbert had passed away by the

time that the doctor arrived. He was

only thirty-eight years old.

The Centre Montville

town correspondent wrote: “Mr. Herbert

Hannan died Wednesday, the eighth, after

suffering from an abscess in the head

which broke and discharged on the brain.

He leaves a wife and ten small children,

who were dependent on his earnings for

their support. The oldest is eleven, and

the youngest a month old. He was an

industrious man and has always been able

to care for his family ...”

It all had happened so

suddenly. Millie had thought that she

and Herbert would grow old together, and

now he was gone. It was all like a bad

dream. Nothing made any sense. She

couldn’t even think about what tomorrow

would bring. She couldn’t organize her

thoughts. She had ten children now

dependent on her, including a one

month-old baby who needed feeding.

Mildred and Gladys tended to the young

ones and put a meager meal on the table.

In a few days, friends

and neighbors brought in firewood,

vegetables and food from their larders.

Herbert had raised a good garden the

year before and had raised a pig. She

had a partial barrel of salt pork in the

cellar, potatoes, salted greens and

perhaps one hundred jars of her home

canning left, but how long would it

last?

At least she still had

her eighty-one year old father to lean

on. Mr. Baker was coming by with his

gasoline engine to saw up the wood.

Millie had no hay to speak of in the

barn, so the next week she sold her

horse to a neighbor. After all, what

good was a horse if you had no feed and

no place to go. With the immediate help

of the neighbors, it seemed that good

will was soon forgotten.

Millie was not eating

well herself. She did not want to take

food from her family. Baby Lester fussed

more and more. He was so tiny, and did

not seem to be growing. She just did not

have enough milk to feed him. In May, at

three months of age, Lester died, just

two months after his father. They buried

the tiny babe beside his father in the

Pine Grove Cemetery in Searsmont.

She struggled on,

thankful for the help of her older

children, even though they were very

young. So much was expected of them. She

was also thankful her family was all

together. Gladys had not been feeling

well. Dr. Ramsay diagnosed her with

rheumatic fever, which caused her to be

blind. As if those problems were not

enough, Papa Boynton, Millie’s father,

contacted pneumonia and died January

12th. He was eighty-two years of age.

His death left Millie feeling completely

drained and alone. She had been doing

some housework, cooking and cleaning for

some of the more affluent farmers’ wives

to bring in food for her children.

It was sometime after

Herbert’s death, and probably after

Lester’s death, Millie couldn’t seem to

remember when because life had all

become a blur in her memory, that the

town selectmen held a meeting. Shortly

after, they came to Millie’s door to

tell her that because of her

circumstances of being a young widow

with all of those children, they had

come to take some of her children away

“to a better life.”

Bertha, age five and a

half, and Daisy, age four years, were

taken away from the only loving family

that they’d ever known to the Girls’

Home, the county orphanage in Belfast.

Roy, who was seven and a

half, was taken to a local farm to work.

Millie was once again in shock. She had

no say in where her children were taken,

nor did she even have a chance to hug

them or to say, “I love you,” or

anything. This was something Daisy

remembered the rest of her life. The

other children were also devastated by

the break-up of the family. They did not

meet again until they were grown.

Millie stopped thinking

about her past year, and again wiped her

hands on her apron. So much had

happened. Here it was, nearly a year and

a half after Herbert’s death. She stood

alone in the kitchen, twisting the apron

in her hands. What was she to do now?

She was thirty-three years old, and once

again “in a family way.” This should

never have happened. The charitable

neighbors had not all been honorable.

She had no one to talk to, no one would

believe the word of a young widow about

a “pillar” of the community.

One fifty year old

neighbor, Joe Chapman had been asking

her to marry him. She didn’t really like

the man, but it seemed as though it was

the only solution to her problems. So,

November 12th, one year and eight months

after Herbert’s death, she and Joe were

married.

The Liberty newspaper

correspondent wrote, “Joe Chapman and

Mrs. Millie Hannan were married last

Saturday night, L. D. Jones, Esq. tying

the knot.” It all seemed very flippant.

Millie often thought about what the

neighbors thought about her. They should

have walked in her shoes, such as they

were, for awhile.

Joe was abusive from the

night of their marriage. He looked down

upon her, accusing her of many things,

and often hit her. Millie thought life

couldn’t get any worse. Three months

after their marriage, George was born.

Joe left, and good riddance. Millie

clung to her baby, George, who went by

the name of Hannan all the days of his

life.

Millie

was told that Roy would be taken to a

farm where he was to be clothed and well

taken care of. A few years later, one of

his sisters saw him driving a horse on

the road. He was thin, dirty, dressed in

rags and covered with lice. He said

often he did not have enough to eat. He

was allowed to come home for a time.

Millie

was told that Roy would be taken to a

farm where he was to be clothed and well

taken care of. A few years later, one of

his sisters saw him driving a horse on

the road. He was thin, dirty, dressed in

rags and covered with lice. He said

often he did not have enough to eat. He

was allowed to come home for a time.

Putting meals on the

table three times a day was often a

challenge. The only bread the family ate

were biscuits made from dough made from

flour, baking powder and milk, when

available. This was usually rolled out

and each biscuit dipped in salt pork fat

or melted lard, heating on the

woodstove. When Millie was rushed, she

mixed the dough a little softer and

dropped by spoonfuls on the baking

sheet, with a dab of hot melted pork fat

on them before baking. These she called

“slut biscuits”.

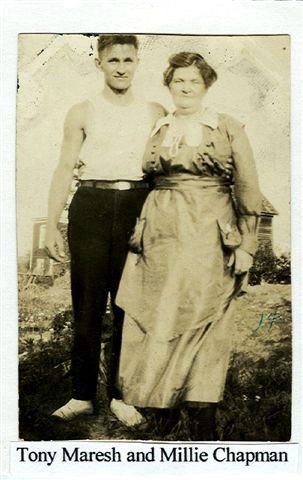

Life improved a little

for Millie as the family grew older.

Mildred married at age seventeen to John

Edgar Perkins, having three children

before Edgar left her to raise the

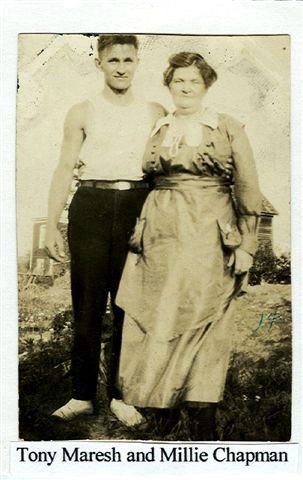

children alone. Gladys married at age

nineteen to a hard-working immigrant

from Russia, Anthony Maresh. Herbert had

been working out since he was very

young, helping his mother as much as he

could. In 1924, Mildred, her children,

Gladys and Tony had gone to

Massachusetts to find work there.

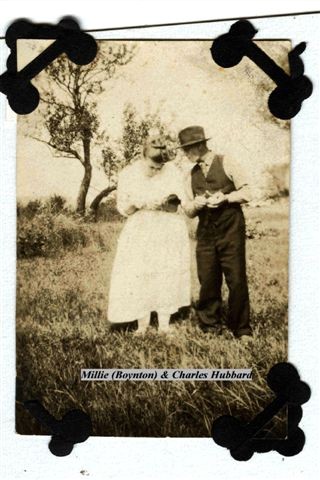

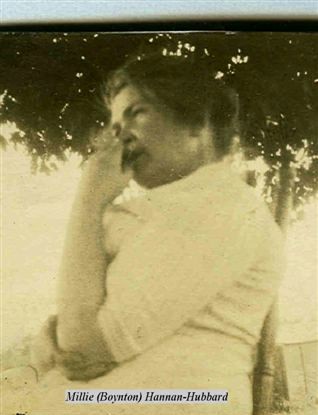

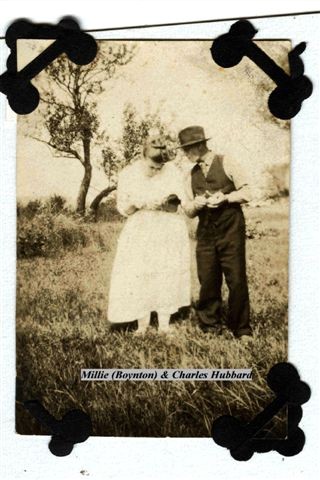

That same year, Millie

married Charles S. Hubbard, aged

fifty-three, in Belfast. Charles and

Millie took her younger sons and went to

Massachusetts, also.

That same year, Millie

married Charles S. Hubbard, aged

fifty-three, in Belfast. Charles and

Millie took her younger sons and went to

Massachusetts, also.

While in

Massachusetts, she came down with scarlet

fever. Millie died at the Boston City

Hospital, age 50 years, 11 months and 15

days. Millie had lived through some hard

times in her short life. How different

life would have been, had she and Herbert

lived to a ripe old age

One

winter night in 1909 Herbert’s cow died.

The local newspaper under the South

Montville town column wrote: “Herbert

Hannan recently lost his only cow and as

he is a poor man, with quite a large

family, his kind neighbor Mr. Baker, has

started a subscription to get another

cow for him. We hope all who have the

opportunity and can help, will put their

hand down into their pocket. A friend in

need is a friend indeed.”

One

winter night in 1909 Herbert’s cow died.

The local newspaper under the South

Montville town column wrote: “Herbert

Hannan recently lost his only cow and as

he is a poor man, with quite a large

family, his kind neighbor Mr. Baker, has

started a subscription to get another

cow for him. We hope all who have the

opportunity and can help, will put their

hand down into their pocket. A friend in

need is a friend indeed.”

Millie

was told that Roy would be taken to a

farm where he was to be clothed and well

taken care of. A few years later, one of

his sisters saw him driving a horse on

the road. He was thin, dirty, dressed in

rags and covered with lice. He said

often he did not have enough to eat. He

was allowed to come home for a time.

Millie

was told that Roy would be taken to a

farm where he was to be clothed and well

taken care of. A few years later, one of

his sisters saw him driving a horse on

the road. He was thin, dirty, dressed in

rags and covered with lice. He said

often he did not have enough to eat. He

was allowed to come home for a time.

That same year, Millie

married Charles S. Hubbard, aged

fifty-three, in Belfast. Charles and

Millie took her younger sons and went to

Massachusetts, also.

That same year, Millie

married Charles S. Hubbard, aged

fifty-three, in Belfast. Charles and

Millie took her younger sons and went to

Massachusetts, also.