Gram Lermond,

loved by all

Annie was nearly awake. She heard a voice

speaking to her, “Mrs. Lermond, Mrs.

Lermond.”

Whose voice was this? No one called her

Mrs. Lermond. Her name was Annie Maria.

Papa had always called her “Annie ’Ria.”

What

room is this? Nothing felt familiar.

“Mrs.

Lermond,” the voice again said. “If you’ll

eat some breakfast, we’ll get you up in a

chair to sit in the sun.”

Annie

then remembered that Mildred had brought

her to this place in Rockland, in the

twilight of her life. As she dozed, she

recalled the happy days of her youth on

the hill in Millertown.

Annie

had been born in May of 1882, in

Lincolnville, the only child of Austin and

Callie (Clark) Marriner. She had spent

fun-filled days picking wildflowers and

playing children’s games with her many

cousins.

After all, Mamma had been

the youngest daughter of the 11 children

of John and Mary Ann (Clark) Clark. Even

though Papa also had been an only child,

his great-grandfather Naler Mariner, had

been among the early settlers of the town

of Lincolnville, then called New Canaan.

Naler had built a log cabin behind the

present house. Papa had cousins galore,

both in the neighborhood and spread out

across America. After all, Mamma had been

the youngest daughter of the 11 children

of John and Mary Ann (Clark) Clark. Even

though Papa also had been an only child,

his great-grandfather Naler Mariner, had

been among the early settlers of the town

of Lincolnville, then called New Canaan.

Naler had built a log cabin behind the

present house. Papa had cousins galore,

both in the neighborhood and spread out

across America.

Just

down the road lived cousin Effie Miller.

Across the fields lived another cousin,

Horace Miller. In the other direction was

cousin Clair Pottle. Effie and Annie

romped together across the fields. They

attended school in the Millertown

district.

One day

they even rode to Camden with Papa on his

trip to Rockland with a load of lime casks

made in his cooper shop. While in Camden,

they had their picture taken together. A

fine picture it was, printed on tin. Papa

picked them up on his way back through

town.

Annie

remembered the trips to Boston when she

was 10 years old and later, with Papa and

Mamma. Papa had gone there to arrange for

sales of his apples and farm produce. It

was a great trip on the Eastern Steamship

liners. They also visited relatives in

Boston and the surrounding vicinity.

When it

became time for her to go to high school,

in 1899 and 1900, the neighborhood

community hired Miss Mary B. Grant to

teach the children at the Old Town House,

down below Judge Miller’s.

The

building had been built in 1820 and was

old when they attended school there. Each

student brought a stand and a chair from

home to use as a desk. Most of the

students were related, among whom were

Horace, Effie, Clair Pottle, the Pitcher

girls, Millers, McKinneys, Thomas, Pattens

and others who Annie could not recall.

Papa had

an interest in a movement called the

Grange, even before Annie was born. She

remembered going as a small child, to

Grange meetings at Farmer’s Pride and

Mystic Grange in Belmont.

On April

28, 1898, mostly through the efforts of

her father, Austin, and other civic-minded

neighbors, 27 of them met at the Old Town

House for the purpose of organizing a

Grange by the name of Tranquility. Papa

was installed as the first Master.

Sixteen-year

old Annie was the log-keeper, writing down

the happenings of the group. For the rest

of her life, Annie was active as a member

of the Grange, which was a “second-home”

for the members.

Annie

recalled that in 1899, a year later, the

group decided it was time to have its own

hall. After fund-raising suppers, dances,

pledges and offers from volunteers, the

grand building was completed in 1904. The

satisfaction in their new building was

short-lived when the hall was destroyed by

fire. Neighbors and Grange members managed

to save some of the windows, chairs, and

desks which were stored in the Old Town

House.

Annie

and Effie often walked across the woods to

visit Aunt Villa Pottle. Cousin Clair

would have friends visiting, doing all of

the things that young men do. They enjoyed

racing their horses, helping with the

haying and other farm chores.

Among

the friends were: Edgar Levenseller; his

sisters, Addie and Jennie; Bernard,

Frankie and Richard Lermond; with their

sisters, Maud and Katie Lermond.

What fun

the group of young people had — sleigh

rides in the winter and feasting at

picnics and swimming in the pond across

from Addie and Jennie's house, in the

summer.

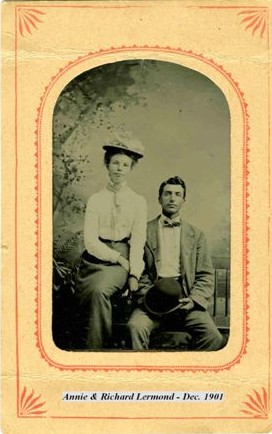

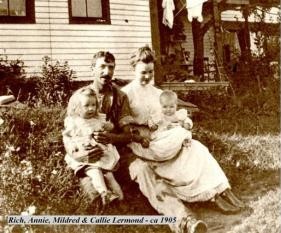

Richard

Lermond, who everyone called Rich, and

Annie had a mutual attraction. The couple

was soon courting. They attended the

dances for the Grange, card playing and

enjoying each other’s company. Rich was

handsome, witty and a catch for any young

girl. He soon asked Papa for her hand in

marriage.

On Christmas Eve, 1901,

Rich and 19-year-old Annie went on a

sleigh ride to Camden, where they were

married by L. D.. Evans, justice of the

peace. It was a crisp, cold moonlit night

as they rode back to Lincolnville, via the

Turnpike, with sleigh bells ringing, to

the Old Town House where a party was

waiting. Rich was so happy to have her as

his bride, that as they danced around, he

picked her up, dancing an Irish jig. On Christmas Eve, 1901,

Rich and 19-year-old Annie went on a

sleigh ride to Camden, where they were

married by L. D.. Evans, justice of the

peace. It was a crisp, cold moonlit night

as they rode back to Lincolnville, via the

Turnpike, with sleigh bells ringing, to

the Old Town House where a party was

waiting. Rich was so happy to have her as

his bride, that as they danced around, he

picked her up, dancing an Irish jig.

The

couple settled in on the hill in the old

Marriner farmhouse. The next year, 1902,

was an unhappy year for the couple.

Grandmother Clark had died before Annie

was born. Annie recalled hearing that Dr.

Neal had made an autopsy on grandmother.

He discovered two tumors, weighing abut

six and four pounds, respectively. He

thought they had caused her demise.

Grandfather

Clark moved up to the hill to live with

the family. He died in January 1902, one

week after Annie and Rich’s wedding. He

was 90 years old.

Rich’s

mother, Mary had been born in Ireland.

Annie loved to hear her Irish accent, and

to listen to Mary and her daughters sing.

Then, Aug. 9, 1902, seven months after

their wedding, Rich’s lively soft-spoken

mother, who had been kicked in the head by

a horse, died at age 59.

One week

later, Rich’s sister, Maud died. She was

29. Two months after Maud’s death, Rich’s

little brother, Frankie died, at age 27.

All three had died of tuberculosis. Rich

was grief-stricken. Theirs had been such a

happy close-knit family.

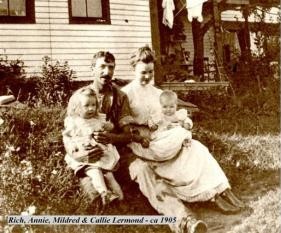

Mildred was born in 1903,

followed by Callie, Mary, Margaret and

Bernice. Callie was named after Mamma and

Mary after Rich's mother. Baby Callie was

born in February 1905. Mildred was born in 1903,

followed by Callie, Mary, Margaret and

Bernice. Callie was named after Mamma and

Mary after Rich's mother. Baby Callie was

born in February 1905.

Two

months later, Mamma died of heart trouble,

at age 51. Mamma had always been there for

Annie, who had been an only child. Mamma

had only been sick a few weeks, when

suddenly she was gone. Mamma had been

active in the Grange, always helping those

who were sick or in need. At her funeral,

nearly every member of the Grange

attended.

After

the Grange Hall burned in 1904, some

members were hesitant to rebuild. Annie

and Papa were among those who vowed to

press on and rebuild. Papa and Rich helped

work on the second hall, while Annie and

the other women prepared meals for the

carpenters. At last, they had the building

up, ready for the plasterers.

Annie

remembered the day, May 25, 1908, when the

phone rang from Lincolnville Centre

phone office, telling everyone on the line

that Tranquility Grange was again burning.

Papa and Rich went down to help fight the

fire, but alas, this hall also was

destroyed. Annie wept. All that work, gone

up in smoke. It was rumored that one of

Annie’s cousins had set the fire.

They

were back to having no hall. In the summer

and early fall of 1908, the Grange cleared

up the debris of the burned Grange site. A

determined group once again hired

carpenters, with much volunteer labor and

materials, and set about to build another

Grange Hall. This time instead of plaster,

they put in beautiful pressed metal walls

and ceilings. The new Grange hall was

ready for use in January of 1909. This

hopefully would be the last Grange Hall

they would have to build.

Life was simple

for Rich and Annie on the hill. The family

enjoyed Grange picnics at Oakland Park in

Rockport. It was a happy time when the

Grange families got together, eating,

drinking, with the children playing and

romping in the park. The neighborhood

families also went on group excursions,

complete with picnic lunch. They picked

blueberries to be canned for the winter up

on Stevens Mountain, near home. Life was simple

for Rich and Annie on the hill. The family

enjoyed Grange picnics at Oakland Park in

Rockport. It was a happy time when the

Grange families got together, eating,

drinking, with the children playing and

romping in the park. The neighborhood

families also went on group excursions,

complete with picnic lunch. They picked

blueberries to be canned for the winter up

on Stevens Mountain, near home.

Annie

sewed for her family, making dresses for

the girls, quilts for their warmth and

fancywork for Grange competition at the

fair. She recalled that one time, Rich’s

sister, Kate, had given her bolts of white

material. She had made the girls white

dresses, which they wore with pride to the

Grange picnic at Oakland park.

Dr.

Elmer Gould diagnosed Papa with influenza

in the spring of 1915. Julia was born in

the fall of 1915, delivered by Dr. Gould.

Julia was a beautiful baby, and loved by

Annie, Rich, Papa and all of her sisters.

Papa never really rallied from the flu. He

died in February 1916, at 69 years of age.

Annie and Rich’s baby girl, Julia, died of

pneumonia New Year’s Day, 1917, just over

1 year old. After Papa died, Rich’s

father, who had been alone much since his

wife’s death, moved into the farmhouse

with their family.

The five Lermond girls were

very attractive. Someone once asked Rich

if he regretted not having boys. Rich’s

reply was, “Where there are girls, there

will be boys!” The five Lermond girls were

very attractive. Someone once asked Rich

if he regretted not having boys. Rich’s

reply was, “Where there are girls, there

will be boys!”

The

Lermond home was a hub of activity, with

relatives coming for the summer from

Massachusetts and from across the country.

Callie

was the first to marry in 1923 to J.

Everett Morse of Belmont. Mildred married

Allen Morton in January 1925, followed by

Mary, who married Everett’s brother, Amon

in March, 1925. Rich and Annie soon had a

growing household of grandchildren.

Rich,

being truly Irish, had a taste for

alcohol, much to the chagrin of Papa, who

did not imbibe in alcoholic beverages,

being an abolitionist. Rich made a smooth

hard cider and vinegar from his apple

trees. He passed his secret recipe for

apple cider to his son-in-law, Amon. He

also made home-brew, an alcoholic drink

made from malt and yeast. This was during

the Prohibition era. Annie was not always

tolerant of his drinking habits.

One

time, she secretly knocked the bung out of

his barrel of brew, letting the

foul-smelling beverage go down the cellar

drain. Rich never knew how the bung

happened to come loose.

Annie

would never forget that Tuesday evening,

Dec. 13, 1927. Annie was clearing up the

supper dishes, when Rich came in to tell

her that he’d started the gasoline engine,

used to generate electrical power for the

lights. He went back to the barn, finding

it all ablaze. While attempting to put out

the fire, he was badly burned on his face

and hands. Neighbors were alerted, coming

to help fight the fire with a bucket

brigade, but it was useless. They lost the

buildings, four horses, 10 cows, and six

hogs. They also lost the crop of hay, the

apples stored from his orchards for

shipping, 100 bushel of dry beans, 450

bushel of potatoes, most of the farm

machinery, and all of the household

furniture, some of which had been in the

family for 150 years, back for five

generations.

Annie

was glad Papa was not here to see the

destruction caused by the fire. The

estimated loss was $10,000, which was

partially insured. They concluded the

gasoline engine had exploded.

In the

excitement of the fire, 16-year-old

Bernice carried her nephew, Allen Jr. down

to the neighbor’s, Lucius and Myrabell

Russ.

Allen

Jr. was a chunky child. Bernice told her

mother how her arms had ached carrying the

heavy child. Margaret, then 17, was

credited with saving a wooden chest of

family photos and certificates which were

stored at the top of the stairs. Rich was

taken to the Camden hospital by neighbors

to tend to his burns. He recuperated at

Mildred and Allen’s apartment in Camden.

The

neighbors and members of the Grange

rallied to rebuild the farm buildings. A

benefit was held by the Grange. Rich heard

of a barn on Spring Brook Hill in Camden.

He, his sons-in-law and neighbors

dismantled the barn, hauling it back to

Millertown where they reassembled it.

Kindly neighbors and Grange members

donated some livestock, and household

furniture. Annie and Rich lived in the

room over the cooper shop until the house

was completed enough to live in. Life

slowly returned to normal.

Mildred

and Allen worked in the Woolen Mill in

Camden, leaving Allen Jr. to attend Miller

School, living with his grandparents, Rich

and Annie. In May 1936, Allen Jr. became

sick. He was taken to the hospital in

Rockland, X-rayed, followed by surgery

from which he never recovered. He died May

18, 1936, aged 9 years and 8 months, of

typhoid pneumonia. Annie, and especially

Rich, grieved for the boy who had always

lived with them.

One year

later, on a hot day, June 13, 1937, the

family was called together to search for

Rich. He had not been well. He was

scheduled for an operation on his back at

Waldo County Hospital in Belfast. He had

gone out hunting and had not returned. The

family spread out across the fields,

searching for him. Three hours later, he

was found on a stone wall in the back

field. It appeared that his foot became

caught between two logs on the wall,

causing him to fall upon his gun, which

discharged, killing him.

Rich was

nearly 58 years old. He had always been a

prominent citizen of the town, a farmer

and a cooper. He was an active member of

the Grange, and belonged to King David’s

Masonic Lodge. Whenever there was a need

in the community, Rich would be there with

baskets of food, hay for animals, or

whatever the need might be.

Annie

wept as she recalled her loss. Life was

lonesome without Rich. Callie, Everett and

the girls moved in with her to help keep

up the farm. Mildred and Allen had taken

over Grandfather Lermond’s farm across the

woods. One day, as Everett was leaving to

go to work, he met Allen leading his

cattle up over the hill to the barn.

Mildred and Allen moved into the big old

farmhouse with them. Callie, Everett and

the girls soon purchased the old Fredson

farm up the road.

In the

fall of 1941, Mary and Amon’s little

11-year-old daughter, Janette became sick

and needed surgery for a serious sinus

disease. Dr. Carl Stevens of Belfast

performed the surgery, but Janette died in

October of that year.

Around that time, Annie

moved into Aunt Frances Churchill’s home

down by the cemetery, where she lived for

a few years. Bernice and Ivan lived next

door. Annie tended their young children

while Bernice worked. Harry Dole, Aunt

Carrie’s third husband, who was widowed,

lived next door in Grandfather Clark’s old

home. Harry, who was Annie's second

cousin, visited Annie several evenings a

week. They enjoyed sitting on the porch

and chatting about family and the

happenings of the day in the evening

hours. Around that time, Annie

moved into Aunt Frances Churchill’s home

down by the cemetery, where she lived for

a few years. Bernice and Ivan lived next

door. Annie tended their young children

while Bernice worked. Harry Dole, Aunt

Carrie’s third husband, who was widowed,

lived next door in Grandfather Clark’s old

home. Harry, who was Annie's second

cousin, visited Annie several evenings a

week. They enjoyed sitting on the porch

and chatting about family and the

happenings of the day in the evening

hours.

Margaret

and Bob lived across from Lucius and

Myrabell Russ. In 1951, Bernice opened a

lunch stand at the head of Megunticook

Lake. Annie enjoyed helping Bernice at

Sunset Cove, greeting old friends and

neighbors who she’d known all of her life.

In her

sunset years, when she was unable to work,

Annie returned to the farm where she’d

been born. Mildred had an apartment made

for her upstairs in the farmhouse that

Rich had built.

Annie

had seen so much in her nearly 87 years.

Now she was in an unfamiliar room. She

thought she heard Rich’s familiar loving

voice as an angel held her hand. The nurse

was coming back to sit her in the sun.

There was no need now. The cares of life

fell off, as Annie reached for Rich’s

hand, stepping into her new life, with all

of those whom she had loved so dearly.

Annie

had been called Gram Lermond by her many

grandchildren and great-grandchildren. She

died in Rockland on April 13, 1969. She

was buried in Union Cemetery with Rich,

their baby daughter, Julia, Papa, Mamma,

Little Allen, Janette, and all the

generations that had gone before her,

including her great-grandparents who had

been among the first settlers to come to

the town of Lincolnville, building in the

back settlement. Annie had

been the fifth generation to live on the

land deeded to her forebears.

Circa 1969, the farm was

sold by Mildred and Allen, so that the only

memories of the Marriner generations are in

the hearts of her descendants, and in the

Union Cemetery.

|

After all, Mamma had been

the youngest daughter of the 11 children

of John and Mary Ann (Clark) Clark. Even

though Papa also had been an only child,

his great-grandfather Naler Mariner, had

been among the early settlers of the town

of Lincolnville, then called New Canaan.

Naler had built a log cabin behind the

present house. Papa had cousins galore,

both in the neighborhood and spread out

across America.

After all, Mamma had been

the youngest daughter of the 11 children

of John and Mary Ann (Clark) Clark. Even

though Papa also had been an only child,

his great-grandfather Naler Mariner, had

been among the early settlers of the town

of Lincolnville, then called New Canaan.

Naler had built a log cabin behind the

present house. Papa had cousins galore,

both in the neighborhood and spread out

across America.  On Christmas Eve, 1901,

Rich and 19-year-old Annie went on a

sleigh ride to Camden, where they were

married by L. D.. Evans, justice of the

peace. It was a crisp, cold moonlit night

as they rode back to Lincolnville, via the

Turnpike, with sleigh bells ringing, to

the Old Town House where a party was

waiting. Rich was so happy to have her as

his bride, that as they danced around, he

picked her up, dancing an Irish jig.

On Christmas Eve, 1901,

Rich and 19-year-old Annie went on a

sleigh ride to Camden, where they were

married by L. D.. Evans, justice of the

peace. It was a crisp, cold moonlit night

as they rode back to Lincolnville, via the

Turnpike, with sleigh bells ringing, to

the Old Town House where a party was

waiting. Rich was so happy to have her as

his bride, that as they danced around, he

picked her up, dancing an Irish jig.

Mildred was born in 1903,

followed by Callie, Mary, Margaret and

Bernice. Callie was named after Mamma and

Mary after Rich's mother. Baby Callie was

born in February 1905.

Mildred was born in 1903,

followed by Callie, Mary, Margaret and

Bernice. Callie was named after Mamma and

Mary after Rich's mother. Baby Callie was

born in February 1905.  Life was simple

for Rich and Annie on the hill. The family

enjoyed Grange picnics at Oakland Park in

Rockport. It was a happy time when the

Grange families got together, eating,

drinking, with the children playing and

romping in the park. The neighborhood

families also went on group excursions,

complete with picnic lunch. They picked

blueberries to be canned for the winter up

on Stevens Mountain, near home.

Life was simple

for Rich and Annie on the hill. The family

enjoyed Grange picnics at Oakland Park in

Rockport. It was a happy time when the

Grange families got together, eating,

drinking, with the children playing and

romping in the park. The neighborhood

families also went on group excursions,

complete with picnic lunch. They picked

blueberries to be canned for the winter up

on Stevens Mountain, near home.  The five Lermond girls were

very attractive. Someone once asked Rich

if he regretted not having boys. Rich’s

reply was, “Where there are girls, there

will be boys!”

The five Lermond girls were

very attractive. Someone once asked Rich

if he regretted not having boys. Rich’s

reply was, “Where there are girls, there

will be boys!”  Around that time, Annie

moved into Aunt Frances Churchill’s home

down by the cemetery, where she lived for

a few years. Bernice and Ivan lived next

door. Annie tended their young children

while Bernice worked. Harry Dole, Aunt

Carrie’s third husband, who was widowed,

lived next door in Grandfather Clark’s old

home. Harry, who was Annie's second

cousin, visited Annie several evenings a

week. They enjoyed sitting on the porch

and chatting about family and the

happenings of the day in the evening

hours.

Around that time, Annie

moved into Aunt Frances Churchill’s home

down by the cemetery, where she lived for

a few years. Bernice and Ivan lived next

door. Annie tended their young children

while Bernice worked. Harry Dole, Aunt

Carrie’s third husband, who was widowed,

lived next door in Grandfather Clark’s old

home. Harry, who was Annie's second

cousin, visited Annie several evenings a

week. They enjoyed sitting on the porch

and chatting about family and the

happenings of the day in the evening

hours.