An

Irish lass

Mary lay her head deep

into her soft feather pillow on her bed in

Lincolnville. She had walked up behind

George’s young colt, startling both she and

the horse. The horse reacted, kicking Mary

on the side of her head. Her head had a dull

ache, but her memories were vivid. She had

come so many, many miles since her

childhood.

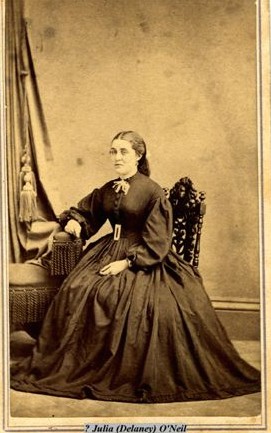

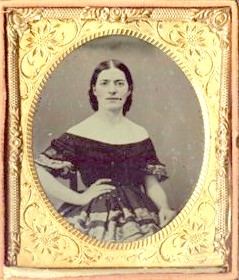

Mary had been

born and soon after baptized on May 2, 1841,

in the parish of Freshford, in Tullaroan,

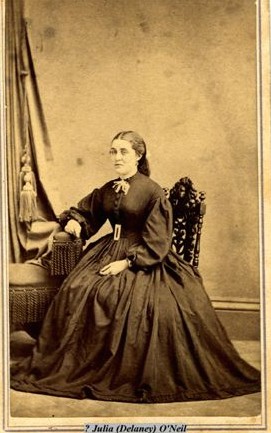

Kilkenny County, in Ireland, the daughter of

Patrick and Julia (Delaney) O’Neil. Her

mother, Julia, had told Mary the village

where they lived was called Knockagrass, or

Lackanagrass, a small subdivision of the

townland of Courtstown.

Mary’s

parents had been married there in March of

1840. They could see the old Courtstown

Castle in the distance. Even when Mary was a

child, the castle was in disrepair.

Though she was young when they left Ireland,

Mary could still see in her mind the

beautiful grassland of old Erin. Her family

was poor, living in a very old hut with a

thatched roof. It was a comfortable home for

Mary, her parents and her three younger

sisters, Catherine, Cecelia and Julia.

That was,

until the landlords wanted all of the land

for themselves. Mary did not understand all

that happened, but she did remember the day

the men in uniforms came, telling Papa that

he and his family would have to leave their

home. Then the men burned the roof of their

home, frightening the children, causing

Cecelia and baby Julia to cry.

Often there

had not been enough to eat. Some of the

neighbors were gone. Mary heard Mamma

whisper to Papa that they had died. It

seemed as though someone died daily. The

Parish Priest came often to the

neighborhood. Mary’s family was Catholic.

Because of the rules and laws in the area,

it was hard for the family to go to church

or Mass, or even to ask the priest for

prayers. Mary’s simple faith as a child

assured her that their Heavenly Father would

take care of them.

Papa worked

for the landowners. He raised crops of

potatoes which they called ‘lumpers‘, corn

and grains. It was hard to feed a growing

family when so much tax of both money and

grains were required to pay the rich

landowners, merchants and the English crown.

Mamma had

made butter, though all but a small amount

went to England for taxes. Papa said while

those around them were starving and dying,

the rich people in England were well-fed.

The law did

not allow the girls to go to school because

they were Catholic. Papa said being Catholic

was one of the reasons the people were

starving. She remembered for the last two

years when he dug his potatoes, they were

rotting, stinking and unfit even to feed

hogs. Papa had called it a ‘blight’. Papa’s

potatoes were not the only ones that were

bad. No one in the neighborhood had potatoes

to eat.

There was no

one for the family to go to for help. Both

Papa and Mamma’s parents were old. They

could not help because they too were hungry

and poor. One day, Papa said they were going

to Liverpool where they would board a ship

to go to Canada, which was nearly on the

other side of the world. Many of the

neighbors were also going. They said goodbye

to all the relatives. There was much crying.

Mary did not realize then that she would

never see most of them again.

Waiting in

Liverpool was not pleasant. They stayed with

others they knew, all of them sleeping in a

long shed, built to house the people waiting

for the ships to leave.

They did not

have much for worldly goods to take with

them. Once aboard the ship, life on the

three-week voyage was almost unbearable.

There were hundreds of men, women and

children in a dark place in the bottom of

the rickety old ship, which creaked and

moaned, as did those aboard who suffered

from seasickness, fever, dysentery and many

other sicknesses. Some seemed to be insane,

ranting and raving constantly. People here

also died daily.

The smell was

a mix of a putrid aroma, a smell Mary never

forgot. The food was bad, salty, and there

was very little of it. They were given a

small ration of water, which was never

enough. Mary later learned they were aboard

what was called a “Coffin Ship.”

The family

arrived in late fall in Montreal, Canada.

Mary thought that it had been in 1853. The

conditions there were not much better than

they had been in Liverpool, and they resided

in long barns in the slums. Their ragged

clothing did little to keep out the cold.

Mamma

was soon to have another baby. Papa worked

at whatever job he could find, but there

were hundreds of Irish fathers in Canada

looking for work. Papa felt he had to keep

his growing family together, to make a

better life for them. Mamma

was soon to have another baby. Papa worked

at whatever job he could find, but there

were hundreds of Irish fathers in Canada

looking for work. Papa felt he had to keep

his growing family together, to make a

better life for them.

Mamma

convinced him to take the four little girls

and go to Massachusetts where he had heard

there was work. Once he got them settled in

with the Ryan family, who had come all the

way from Ireland with them, he could return

for her and their new baby.

So, Papa took

12-year-old Mary, 10-year-old Kate,

5-year-old Cecelia and baby Julia, then only

2, on the giant train to Northampton, Mass.

The families had arranged to live together

until they could make it on their own. Papa

went back to Canada for Mamma and baby

Ellen.

Papa worked

as a manual laborer. He took any job that

was available, from cleaning out stables to

slopping hogs and digging ditches. When Mary

was about 14, she worked in a button shop,

followed by the other girls as soon as they

were old enough.

Later, Mary

went to work in the Florence Hotel, working

for Mrs. Sarah Abercrombie as a maid. The

hotel was a boarding house, where there was

always work to do. Mary lived at the hotel.

She could never have imagined before she

came to America of having indoor plumbing,

water in the sink and in the toilet. She

scrubbed and cleaned, made beds, did

laundry, cleaned slop buckets, spittoons,

and so many other things. The work was

arduous, and the days were long, but with

all of the family members diligently working

and saving, and after sending money home to

grandparents and other relatives struggling

in old Ireland, they got a better place to

live, eventually buying a house in Leeds.

There was a

new Catholic church within walking distance

of where she lived. She kept in close

contact with her mother and siblings.

In

Massachusetts, brothers John and Richard

were born. But Papa had grown old much

before his time. They had come to Leeds in

about 1854. Mary saw her father struggle in

the homeland to feed his family, keeping

them from the workhouses, and together

through the long journey from the old

country.

He worked

from sunup to sundown every day of the week,

while trying to observe his Catholic

Sabbath, only to get sick with Typhoid

fever. Papa died May 5, 1864 in Leeds. He

was buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery in

Easthampton, Mass. He was only fifty-one

years old. Rose was born the year Papa died,

leaving mother with eight children. Thank

God, the eldest girls were able to help

support the family.

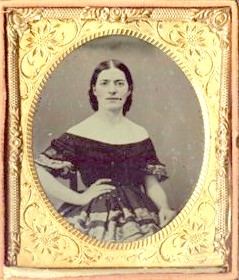

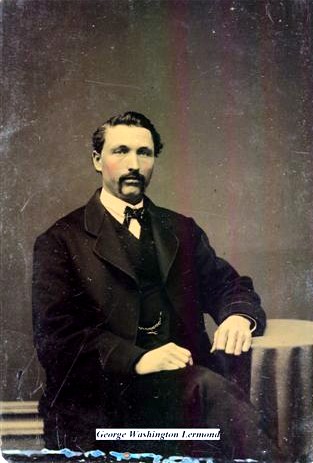

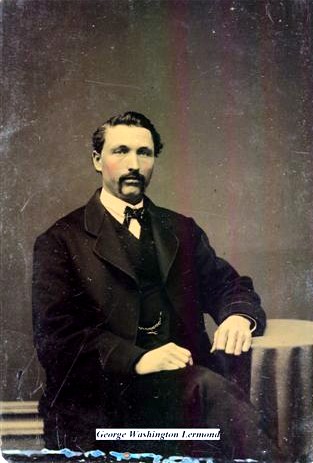

Mary recalled the day she met

a handsome young man from Maine by the name

of George Washington Lermond. George also

had Irish roots, but he was not Catholic.

Their love prevailed. Mary and George were

married in September 1866, two years after

Papa had passed away. When Mary left

Northampton to marry George, Sarah

Abercrombie gave her a little photo album. Mary recalled the day she met

a handsome young man from Maine by the name

of George Washington Lermond. George also

had Irish roots, but he was not Catholic.

Their love prevailed. Mary and George were

married in September 1866, two years after

Papa had passed away. When Mary left

Northampton to marry George, Sarah

Abercrombie gave her a little photo album.

Mary left her

home and close-knit family, moving with

George to Connecticut where his older

brother, Isaac lived. Their first son, Fred

was born in Connecticut.

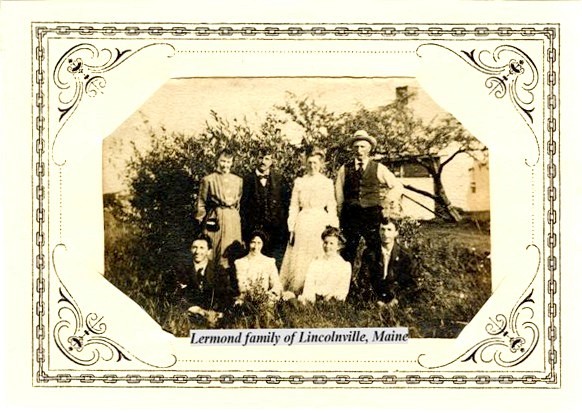

George

decided it was time to take his family back

to Maine. They first lived on Park Street in

Rockland, where Julia Katherine [called

Katie], Flora Maud [called Maud], George

Patrick, Richard John and Frankie were born.

Mary kept in

touch with her family in Massachusetts,

having photos taken of her family in

Rockland to send home. In return, she

received photos from her mother, siblings

and their families, which Mary kept in the

little album that Mrs. Abercrombie had given

her.

George worked

as a laborer, though he wanted a farm.

Coming up to Lincolnville in 1882, he and

Mary purchased the Knight farm in the

western part of town, near Levenseller Pond.

Their near neighbors were Frank and Cynthia

Levenseller, (see Levenseller)

whose children were Jennie, Edgar and Addie.

The children were great friends playing

together. They attended Lamb school, where

Frank Levenseller sometimes taught.

Mary once

wrote to one of her sisters that she was

ostracized in Lincolnville until her

children were grown because she was a

Catholic in a Protestant community. The

nearest Catholic church was in Camden.

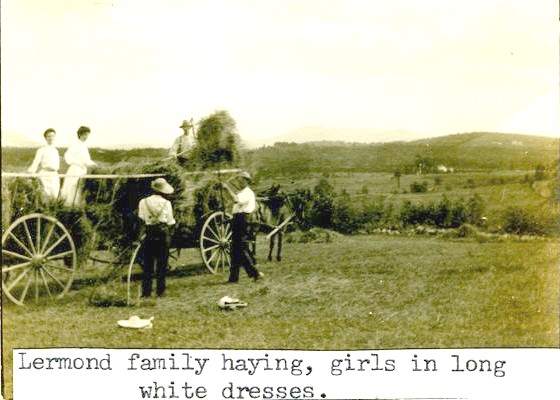

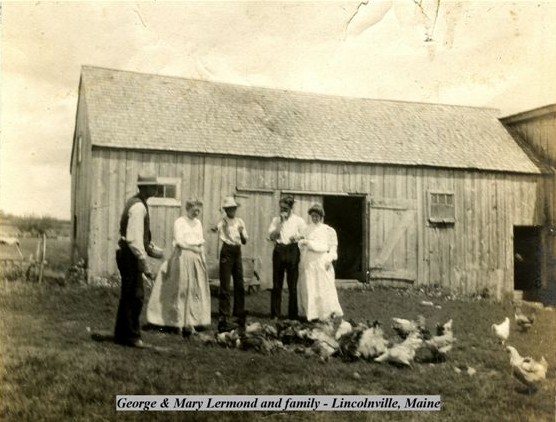

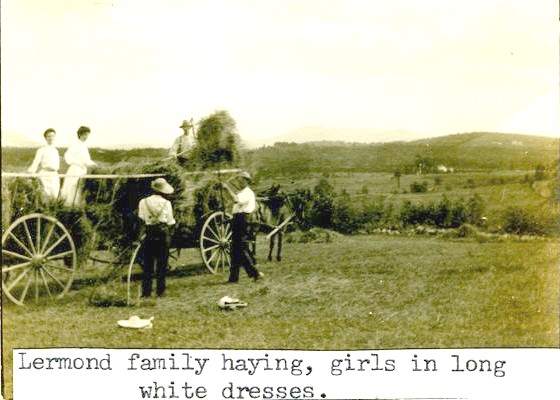

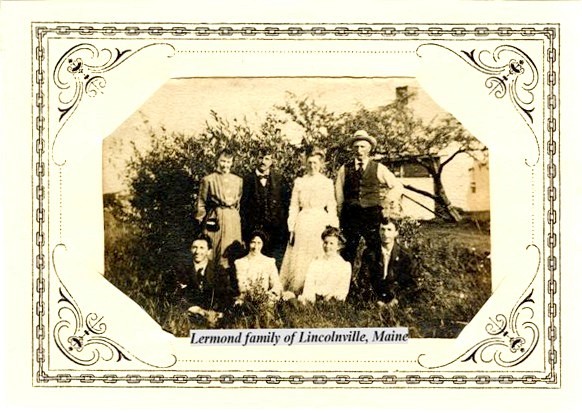

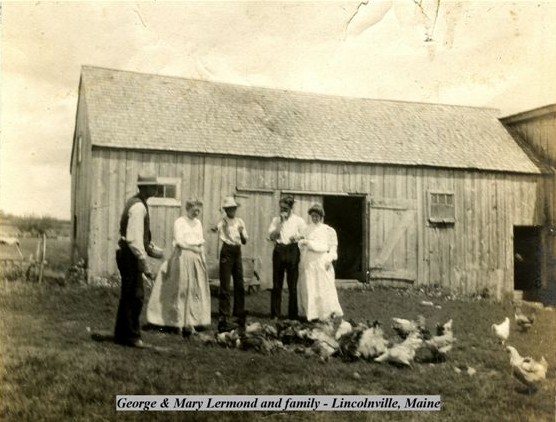

What a joyous time Mary and

her family shared! George raised the usual

farm animals, including cows, hens, ducks,

sheep and his prize horses. The family made

a game of getting in the hay, working

together in the garden that George had

planted, or just feeding the chickens. They

raised many vegetables, which they put up

for the winter, including potatoes of

several kinds. Mary baked, boiled, cooked

and canned. She made butter from the Jersey

cows' fresh thick cream. Never again would

she go hungry, nor ever see her children

begging for food and water. How she thanked

God for that! What a joyous time Mary and

her family shared! George raised the usual

farm animals, including cows, hens, ducks,

sheep and his prize horses. The family made

a game of getting in the hay, working

together in the garden that George had

planted, or just feeding the chickens. They

raised many vegetables, which they put up

for the winter, including potatoes of

several kinds. Mary baked, boiled, cooked

and canned. She made butter from the Jersey

cows' fresh thick cream. Never again would

she go hungry, nor ever see her children

begging for food and water. How she thanked

God for that!

Mary and her

daughters had beautiful singing voices. They

would sing as they worked around the fine

old farmhouse. The boys were lively lads.

The family had picnics, played with their

animals, clowned around, laughed and had a

great time together.

Mary, George

and the children occasionally took the

Boston Steamer from Camden to Massachusetts

to visit her family, and to Connecticut to

visit Isaac and his family. Mary’s siblings

all had families of their own.

Mary’s family

was grown. Fred married Edith Smith in 1893.

Katie married Sylvanus Griffin in 1897 and

Richard married Annie Marriner in 1901.

George moved to Massachusetts where he was

engaged to Julia Lenehan. Kate and Sylvanus

moved to Massachusetts also. They had a

small son, Leonard, who died as an infant.

Mary wept as

she recalled her beautiful twenty-nine year

old daughter, Maud, developing tuberculosis.

Maud died in April of 1902. Mary had begged

George to allow her to call a priest before

Maud died. He had finally relented. While

the priest was in their home, Mary asked for

blessing for her family. Mary and Frankie

both suffered from the effects of

tuberculosis.

Mary kept her

faith in a loving God throughout some

difficult times in her life. God had been

faithful to her. The angel at her side was

proof of that. Mary quietly passed away of

heart failure Aug. 9, 1902, four months

after Maud’s passing. She was fifty-nine

years old. Two months later, her beloved

son, Frankie, passed away of the dreaded

disease Oct. 3, 1902, at the age of twenty.

Only ten

years later, her youngest son, Bernard,

succumbed to the same disease, aged

twenty-eight. They are buried together in

the Upper Cemetery in Lincolnville. It could

truly be said of Mary, “Her children shall

arise up, and call her blessed.” (Proverbs

31:28)

|

Mamma

was soon to have another baby. Papa worked

at whatever job he could find, but there

were hundreds of Irish fathers in Canada

looking for work. Papa felt he had to keep

his growing family together, to make a

better life for them.

Mamma

was soon to have another baby. Papa worked

at whatever job he could find, but there

were hundreds of Irish fathers in Canada

looking for work. Papa felt he had to keep

his growing family together, to make a

better life for them.  Mary recalled the day she met

a handsome young man from Maine by the name

of George Washington Lermond. George also

had Irish roots, but he was not Catholic.

Their love prevailed. Mary and George were

married in September 1866, two years after

Papa had passed away. When Mary left

Northampton to marry George, Sarah

Abercrombie gave her a little photo album.

Mary recalled the day she met

a handsome young man from Maine by the name

of George Washington Lermond. George also

had Irish roots, but he was not Catholic.

Their love prevailed. Mary and George were

married in September 1866, two years after

Papa had passed away. When Mary left

Northampton to marry George, Sarah

Abercrombie gave her a little photo album.  What a joyous time Mary and

her family shared! George raised the usual

farm animals, including cows, hens, ducks,

sheep and his prize horses. The family made

a game of getting in the hay, working

together in the garden that George had

planted, or just feeding the chickens. They

raised many vegetables, which they put up

for the winter, including potatoes of

several kinds. Mary baked, boiled, cooked

and canned. She made butter from the Jersey

cows' fresh thick cream. Never again would

she go hungry, nor ever see her children

begging for food and water. How she thanked

God for that!

What a joyous time Mary and

her family shared! George raised the usual

farm animals, including cows, hens, ducks,

sheep and his prize horses. The family made

a game of getting in the hay, working

together in the garden that George had

planted, or just feeding the chickens. They

raised many vegetables, which they put up

for the winter, including potatoes of

several kinds. Mary baked, boiled, cooked

and canned. She made butter from the Jersey

cows' fresh thick cream. Never again would

she go hungry, nor ever see her children

begging for food and water. How she thanked

God for that!