Visiting hours were over

at the hospital in Belfast, Maine where

Tony was a patient. His youngest son, Bob

and his wife had visited him. Tony told

Bob that his boy, Buster, had visited

earlier with cousin Herbert. Tony recalled

that he’d been having chest pains when his

friend, Dorothy, happened by on her

motorcycle. She had driven him to the

hospital in his car.

Tony was eighty-four

years old. That evening he had told Bob

that he would live to be over a hundred

years because of his family’s longevity.

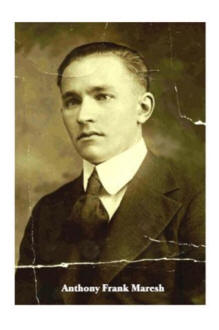

He had been born in 1894, two miles

outside of Moscow, Russia, in what was

called the outskirts of the city, son of

Franz and Julanda Mapeau`. He was named

Anton, after his paternal grandfather. He

had four older brothers, Franz, Josef,

Venzil and Adolf, and an older sister,

Anna. Each of the boys were named after

their father, carrying his name, Franz, as

a middle name. When he was ten years old

his younger sister, Julie, was born. His

family had come to Moscow from Austria,

originally from the Czech Republic.

Anton had been a happy

tow-headed child. His mother called him,

her youngest son, Toniku. He recalled

carefree days as a child, playing on the

floor, singing merrily to his mother as

she taught him his lessons. He would sing

and dance for hours. His mother entered

him in school when he was three years old.

By the time he was four years of age, he

could read and write. The school pushed

him from grade to grade, as he was an

‘advanced’ student. His mother did not

want him to go through high school any

faster, though he graduated when he was

fourteen years of age. If he had been

sixteen, he could have taught grammar

school. He learned French and German in

school, Czech and Hebrew at home from his

mother and grandparents, and Russian, the

language of his country. At school they

wore a type of uniform, sitting two to a

desk, which was made of a sturdy wood.

There was always

something going on in the area as he grew

up. There was a children’s festival,

costing half a ruble to attend, winter

festivals, sliding, skating, and other

winter sports. At the summer festivals,

there would be track racing with the other

boys. In the evening, the festivities

would conclude with a festival of

lanterns.

Transportation was by

horse-drawn trolleys, costing a few kopecs

to ride, but usually Anton and his friends

walked wherever they went. Sometimes

Mother would give him a few kopecs to buy

candy at the store, or to purchase books

about sea captains and going to sea.

The winters in Russia

were very harsh and cold, with much snow.

He was fortunate that his parents were

fairly well-to-do, and that he had warm

clothing, boots, and a Russian Babuska, a

hat made of fur.

Anton had many friends

his own age in the neighborhood. They

hunted, fished, explored the mysteries of

the old city of Moscow, and played around

the majestic medieval Kremlin Park. Anton

recalled that on more than one occasion,

Tsar Nicholas Romanov II came through

their area in an open carriage driven by a

coachman with a tall black hat. Both Tsar

Nicholas II and the coachman sat

straight-backed and stiff as they rode by.

No one made a sound as they stood in awe

watching the black carriage pass by.

One time Anton and his

friends crept through a fence into a park

near where the Romanov girls were playing.

When the girls saw the boys, they

excitedly ran shrieking and squealing.

Guards caught the boys, warning them not

to come that close again.

Both of Anton’s

grandparents lived with them. He

remembered the day that his paternal

grand-father, Anton, came in from hunting

rabbits. The rabbits in Russia were very

large. Grandfather remarked, “I am tired!”

to which Father replied, “What you think,

you’re a young man!” He died at the

kitchen table, eating supper at the age of

one hundred and ten. One of his

grandfathers owned a bologna factory, the

other owned a cigar factory, which were to

be Anton’s, as the youngest son, when he

came of age. Though Anton’s family had

lived in Russia for several generations,

they were required to carry passports, his

mother being a Socialist Jew from the

Czech Republic.

Father had been a

nurseryman, having a hothouse where he

raised many kinds of large fruit, pears,

apples, beautiful roses and more. He would

never reveal his secrets for raising such

large vegetation. Father grew an abundance

of garden produce even though the summers

were short and generally mild,

Anton’s brothers were

engineers. They built windmills and

dynamos, creating electricity. They were

the only ones for miles around to have

lights.

Father had been educated

in Germany. He spoke several languages,

including French, German, and Czech. The

authorities would come for Father to go to

factories to translate for them. Father

told Anton that there were three classes

of people in the changing Russia, peasants

who were uneducated, the middle class, who

were educated, and the rich, who he called

millionaires. Father worked for the rich

upper class people. Mother was well-liked.

She helped her less-fortunate neighbors,

bringing them vegetables, fruits,

firewood., food and baked goods from her

kitchen.

One of

Anton’s uncles had gone to the United

States during the Gold Rush. Anton’s

father had given him the money to go to

America. The uncle had sent a picture from

California, dressed in a fine suit, with a

big gold watch, gold chain and watch fob.

He had never repaid Father. Father made

Anton promise that if he ever got to

America, to never look up his uncle.

One of

Anton’s uncles had gone to the United

States during the Gold Rush. Anton’s

father had given him the money to go to

America. The uncle had sent a picture from

California, dressed in a fine suit, with a

big gold watch, gold chain and watch fob.

He had never repaid Father. Father made

Anton promise that if he ever got to

America, to never look up his uncle.

Another uncle, also named

Anton, was an engineer, building bridges.

He never drank on the job, admonishing

Anton to do the same. When his job was

finished, he would come home to stay with

Anton’s family, bringing a Mexican dog. He

would keep his money in his pocket, and

the dog would protect him and the money.

He would leave a Bismarck for Mother on

the table, with the dog to protect her

also.

Russia was in a turmoil. Many of the

people were opposed to the Tsar’s

monarchy. There was talk of anarchy. In

1897, when Anton was three years old, the

country had been involved in the Boer war.

When Anton was eleven years old, in 1904

and 1905, the country was involved in the

Russo-Japanese War, being defeated.

In 1904,

the officials came for Anton’s oldest

brother, Franz, to serve in the Army.

Father told them, “Get off my property.”

He then took Franz to Germany and put him

on a boat to go to America. On arriving in

the United States, Franz worked as an

engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1904

for 38 cents an hour. From there he went

to Pennsylvania to work in the coal mines

where he lived with a Russian-Polish

family. Franz never married. Anton’s

brothers, Venzil and Adolf, had served in

the Russian Army. When one came home from

the Army, the other went away to serve his

time.. His brother, Joseph, had died as a

young man.

In 1904,

the officials came for Anton’s oldest

brother, Franz, to serve in the Army.

Father told them, “Get off my property.”

He then took Franz to Germany and put him

on a boat to go to America. On arriving in

the United States, Franz worked as an

engineer on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1904

for 38 cents an hour. From there he went

to Pennsylvania to work in the coal mines

where he lived with a Russian-Polish

family. Franz never married. Anton’s

brothers, Venzil and Adolf, had served in

the Russian Army. When one came home from

the Army, the other went away to serve his

time.. His brother, Joseph, had died as a

young man.

Anton’s sister, Anna, had

married a Postmaster in Moscow. His

youngest sister, Julie, later married a

telegraph operator, residing in the Ural

Mountains in Russia.

Many of his friends

worked on farms, though Anton didn’t have

to work. He read his books, longing to

sail on the high seas. The authorities had

come for several of his friends to serve

in the Russian Army. Now that Anton was

out of school, Father feared that the

authorities would come for him also. He

was adamant that his youngest son would

not serve in the Russian Army. Father had

a friend who was a sea captain on the

Black Sea. He wrote him, telling him that

he was sending Anton to Germany to meet

with him, making plans for his youngest

son to leave Russia.

At age fourteen, Father

paid his fare, put him on a train, taking

him to Germany. Anton was in Bremerhaven,

Germany two weeks before World War on 75

Fraulinger Straus [or Street]. His

brother, Venzil was in Germany at that

time. He told Anton to go back to

Bremerhaven, to meet a boat that came

fourteen miles on the river, and to get

out of Russia and not look back.

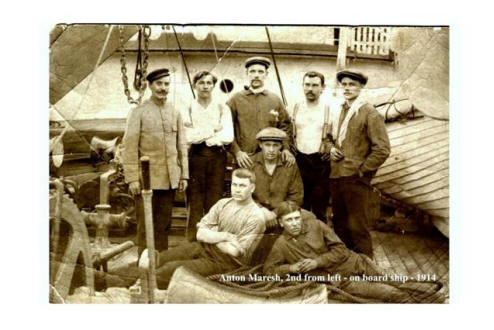

He went to Odessa on the

Black Sea, where he was a ‘mess boy’, or

Captain’s boy. He went with a crew in 1910

on a three-masted schooner, then to a

full-masted ship, where he was a student

to become an officer for thirteen months,

working on the ship for $10 a month. When

he was nineteen years old, in 1913, he was

a qualified as a quartermaster. The pilot

would stand by and tell him where to go.

In the winter, he was a fireman, and a

deck hand in the summer.

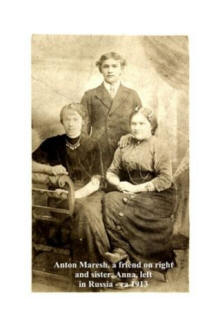

Anton went

home once when he was nineteen years old

in 1913. He had a photo taken with his

sister, Anna, and a friend. He never went

home, nor saw his family, again.

Anton went

home once when he was nineteen years old

in 1913. He had a photo taken with his

sister, Anna, and a friend. He never went

home, nor saw his family, again.

Anton

hired out on a Russian-American passenger

liner, named Dewensk [?]. The war was on

when he left Germany. He was at sea for

several years, stopping at major ports

around the world, stopping in Denmark for

coal and groceries. When they arrived in

Halifax, Canada, the authorities put a

quarantine on the liner and its 3500

passengers from Russia.

Anton

hired out on a Russian-American passenger

liner, named Dewensk [?]. The war was on

when he left Germany. He was at sea for

several years, stopping at major ports

around the world, stopping in Denmark for

coal and groceries. When they arrived in

Halifax, Canada, the authorities put a

quarantine on the liner and its 3500

passengers from Russia.

Anton stayed with an

American convoy, coming into Brooklyn, New

York in 1915, where he and his friend,

Emil, got off the ship. An old German on

the ship told them to remember one thing,

“Don’t bite the hand that is feeding you,

and you’ll get by.” If they were not

caught within twenty-four hours, they were

free. They did not come in as immigrants.

Anton made his way to Old

Forge, Pennsylvania, where his brother

Frank worked in the coal mines. He was

there in July 1915. Frank got him a job in

the mines. They boarded with the Basteks,

a Russian-Polish family in Old Forge. The

boarders were not allowed to fraternize

with the several daughters of the family.

Mrs. Bastek was a

hard-working woman. She would heat the

water for the household, stoke the coal

fire, cook the meals, prepare lunches for

the boarders to take to work, clean up

after them, do the laundry, as well as

tending to a garden, and animals. When the

men came in from work, she would have a

hot bath ready, scrub their backs, black

from coal dust, and prepare the evening

meal.

Mrs. Bastek was a

hard-working woman. She would heat the

water for the household, stoke the coal

fire, cook the meals, prepare lunches for

the boarders to take to work, clean up

after them, do the laundry, as well as

tending to a garden, and animals. When the

men came in from work, she would have a

hot bath ready, scrub their backs, black

from coal dust, and prepare the evening

meal.

Anton recalled one

evening when he came in from work that the

bath was ready, but supper was not. He

took a bath and changed into clean

clothes. Mrs. Bastek asked him if he would

go for the doctor, who came within twenty

minutes. She had asked for hot water and

towels. She had a baby that evening. The

doctor said that she had not needed him.

The next morning, she had breakfast on the

table. Included with the meal was a drink

from the old country, imported strong

‘sweet’ tea, which he drank from a saucer,

through a sugar cube held between his

teeth. For all of his life, he liked a

hearty evening meal, always with meat of

some kind. A young girl named Helen wanted

to get married, but Anton was not ready to

settle down. So, he left Helen and

Pennsylvania.

All Anton knew in English

was “go” and “stop”. He had learned

several languages while at sea in his

youth. The first English that he learned

in 1914, was “son of a bitch”. He learned

to read and write English from reading

newspapers near the Brooklyn Bridge, on a

park bench about 1917. If he was reading

the newspaper, a passing policeman would

let him stay. But, if he was sleeping, the

officer would hit his feet with a billy

club. He carved his initials, AFM, on a

park bench. Because of the War, Anton

discarded the papers that he’d brought

from the old country, including the

passport that he’d carried all of his

life.

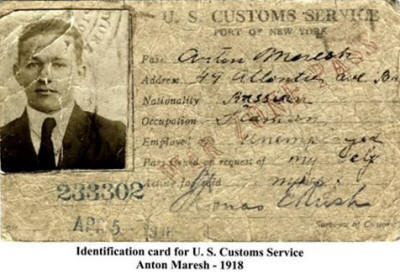

In 1917, Anton registered

for the World War I draft in Brooklyn, New

York. He gave his address as 40 Atlantic

Avenue. At that time he was a captain of a

scow, signing his name as Antonio Maresh.

In April of 1918, he registered with the

U. S. Customs Service in the Port of New

York, signing his name as Anton Maresh, 49

Atlantic Ave, Brooklyn, N. Y., his

occupation was unemployed seaman. In May

1917, he joined the Tide Water Boatmens

Union, Local 847 of the International

Longshoremens Association, signing his

name as Antone Maresh. When the paymaster

at the Port asked his name, he gave it as

Antone. The paymaster called him Anthony,

the name he went by from that time forth,

using the nickname, Tony.

From New

York, Tony made his way to northern Maine,

where he worked in the lumber camps.

Somewhere along the way, he met Carney

Shure, also a Russian Jew, who had

purchased the Ira Cram mill in Montville,

Maine. He told Tony that if he came to

Montville, that he would give him a job.

From New

York, Tony made his way to northern Maine,

where he worked in the lumber camps.

Somewhere along the way, he met Carney

Shure, also a Russian Jew, who had

purchased the Ira Cram mill in Montville,

Maine. He told Tony that if he came to

Montville, that he would give him a job.

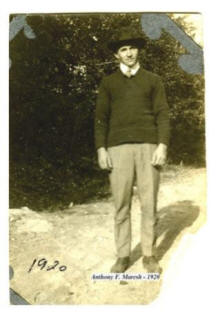

Tony arrived in Montville

around the last of 1919. Working in the

Shure mill, he met the Hannan boys who

worked in the mill also. They invited him

home with them where he met their sister,

young Gladys Hannan. They courted for a

time, marrying in October 1920. Gladys was

the next eldest daughter of Herbert and

Millie (Boynton) Hannan. Her father has

passed away many years before.

The young couple first

lived in ‘The Camp’, a small house owned

by Carney Shure in the Kingdom, Montville,

Maine. Gladys’ sister, Mildred, had three

young children. Her husband had left her

to raise the children alone. The young

people decided that they would go to

Massachusetts where there was more work

with better pay.

Tony and Gladys lived in

Allston, Wellesley, and on Summer Street

in Natick, before purchasing a home at 34

Orchard Road in East Natick in 1934. Tony

worked at various jobs, before obtaining a

job with the Boston and Albany Railroad,

which was later merged with New York

Central. Because Tony spoke seven

languages, he was a natural to become a

section foreman on the railroad, which

employed men from many nationalities,

working for the railroad for thirty-seven

years. He joined the Brotherhood of

Maintenance of Way Employees in 1936,

retiring in 1960.

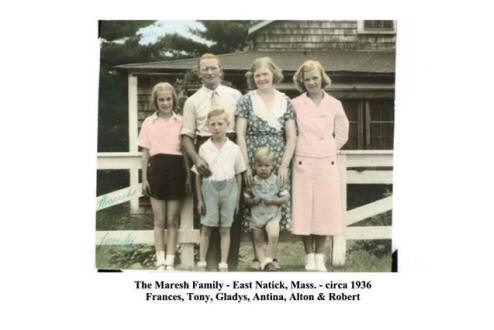

Tony and

Gladys were the parents of five children,

born in Massachusetts, Antina, Frances

Muriel, twins, Anton Frank and Alton

Francis, and the youngest, Robert. Anton

Frank died at age three months of

pneumonia, and buried in Wellesley, Mass.

Alton, who was called Buster, also had

pneumonia, which left him severely deaf.

Tony and

Gladys were the parents of five children,

born in Massachusetts, Antina, Frances

Muriel, twins, Anton Frank and Alton

Francis, and the youngest, Robert. Anton

Frank died at age three months of

pneumonia, and buried in Wellesley, Mass.

Alton, who was called Buster, also had

pneumonia, which left him severely deaf.

In 1942, Tony and Gladys

returned to Old Forge, Penn.. Mrs. Bastek

confirmed to Gladys the story of her

having a baby, and then getting up the

next morning to feed the boarders. They

visited the mine fields where Tony and

Frank had worked. They also visited New

York, and found his initials on the park

bench, that he’d carved so many years

before.

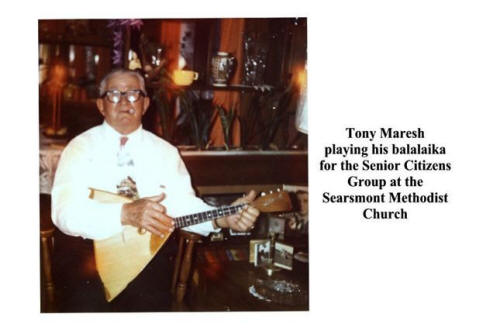

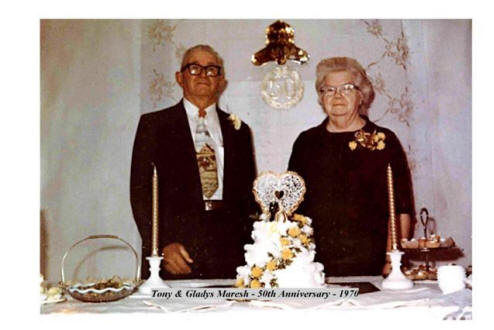

In 1950, Tony and Gladys

purchased a farm to retire to in

Searsmont, Maine. Three of their children

moved to the farm the next year. When Tony

retired from the railroad in 1960, he and

Gladys moved to Maine to spend their

remaining years. Tony enjoyed hunting, and

was an avid fisherman. He was a member of

Quantabacook Masonic Lodge.

Gladys

passed away in 1974 of cancer. Tony and

Buster remained on the farm until that

fateful day that he went to the hospital

in July of 1980. Later, on the night that

he told Bob that he would live to be over

a hundred, he went to join his family on

the golden shore. He was nearly

eighty-five years of age. He is buried in

Hillside Cemetery in Belmont, Maine with

Gladys, his wife of over fifty years.

Gladys

passed away in 1974 of cancer. Tony and

Buster remained on the farm until that

fateful day that he went to the hospital

in July of 1980. Later, on the night that

he told Bob that he would live to be over

a hundred, he went to join his family on

the golden shore. He was nearly

eighty-five years of age. He is buried in

Hillside Cemetery in Belmont, Maine with

Gladys, his wife of over fifty years.

Tony’s father, Franz, had

died in Russia in 1925. His mother

returned to Praha, Austria, where she died

in 1956. Tony‘s brothers, Venzil and

Adolf, and their families resided in the

Czech Republic.

[Much of this story was

obtained from interviews with Anthony F.

Maresh in 1979 and 1980. It is as told,

and may not always be substantiated, but

it gives a picture of a Russian immigrant

to America, with glimpses of his life in

the old country. Tony had at least three

letters from his mother, who was in Praha,

in which she begged him to keep in touch.

He left Russia in 1908, returned once as a

young man in 1913, and one of his desires

in old age, was to once again return,

though none of his family lived in Russia

then.]