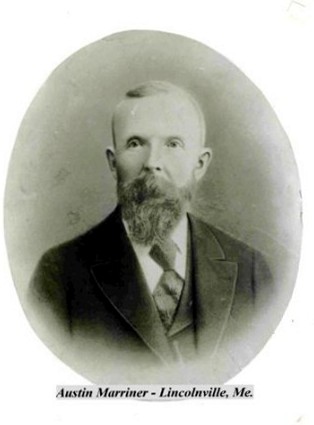

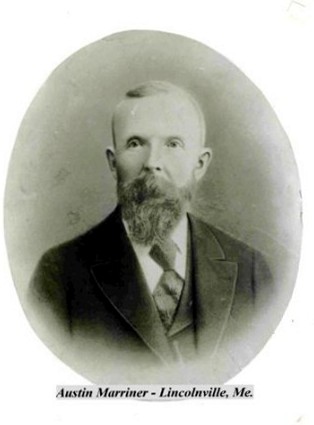

Austin

Marriner lived a simple life on the

hill in Millertown. He was born in

1846 in the house built by his

grandfather, Joseph Mariner. The

land was homesteaded before the

incorporation of the Town of

Lincolnville in 1802. It was then

called New Canaan. The Bible

describes the Land of Canaan, as a

good land, a land of plenty, of

grain, fruit and honey. The old farm

had provided a good living for the

generations who had lived there. The

Mariners [as it had been spelled in

the old days] had come up from Bath

[now Maine] about 1777. Naler,

Austin’s great-grandfather, with his

sons, Jonathan and Philip, settled

on adjoining lands. Philip left his

homestead early, moving to

Searsmont.

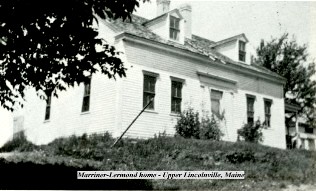

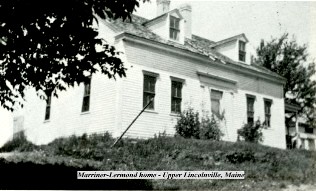

Naler had

built a log cabin behind the present

house. The indentation was still

visible in the ground. The property

passed from Naler and Ruth Mariner

to their son Joseph Mariner, who in

turn passed it on the William and

Sarah (Jackson) Marriner. Austin had

inherited it from his father,

William, intending to pass it on to

a son, but that was not to be.

Naler had

built a log cabin behind the present

house. The indentation was still

visible in the ground. The property

passed from Naler and Ruth Mariner

to their son Joseph Mariner, who in

turn passed it on the William and

Sarah (Jackson) Marriner. Austin had

inherited it from his father,

William, intending to pass it on to

a son, but that was not to be.

Though

the house was situated on a hill,

the farm land and fields were flat.

Over the years, clearing the fields

of rock, to plant crops, the long

stone walls had evolved.

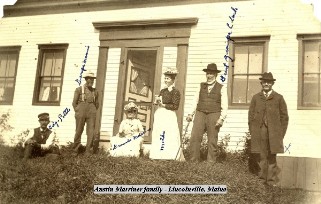

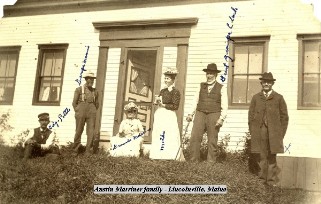

Many of

the neighbors were related, all

descendants of the early settlers of

the town. Austin brought his bride,

Callie Clark, from down on Clark’s

Corner to the farm in 1873, after

being married by J. D. Tucker, Esq.

It was nine years before their only

child, Annie Maria was born. Austin

enjoyed teasing Annie, calling her

“Annie ‘Ria”.

Many of

the neighbors were related, all

descendants of the early settlers of

the town. Austin brought his bride,

Callie Clark, from down on Clark’s

Corner to the farm in 1873, after

being married by J. D. Tucker, Esq.

It was nine years before their only

child, Annie Maria was born. Austin

enjoyed teasing Annie, calling her

“Annie ‘Ria”.

Austin was

an active farmer, planting crops as

well as many kinds of apple and pear

trees, which he took great pride in.

He made barrels in his cooper shop,

on rainy days, and in cold, wintry

weather. He shipped his apples and

farm produce on the Boston Steamers

for Massachusetts markets in his

well-made barrels. He also made

casks for the lime industry and his

own cider-vinegar production. Austin

himself was a temperance man, who

did not indulge in alcohol.

Austin was

an active farmer, planting crops as

well as many kinds of apple and pear

trees, which he took great pride in.

He made barrels in his cooper shop,

on rainy days, and in cold, wintry

weather. He shipped his apples and

farm produce on the Boston Steamers

for Massachusetts markets in his

well-made barrels. He also made

casks for the lime industry and his

own cider-vinegar production. Austin

himself was a temperance man, who

did not indulge in alcohol.

Austin

was known as being a strong-willed

and stubborn man. His son-in-law,

Rich, told the story of Austin and

his horse Bill. Rich said that

Austin led the horse from his stall

in the barn to the watering trough

twice a day. If Bill did not drink,

he would not have water for the rest

of the day. It seems that Bill was

as ornery as Austin. When Bill

refused to drink, Austin pushed his

head into the trough. Bill still

didn’t drink, so Austin held his

head down until he did drink. Rich

said that the old saying, “You can

lead a horse to water but you can’t

make him drink” wasn’t so. Austin

proved that “you can make him

drink”.

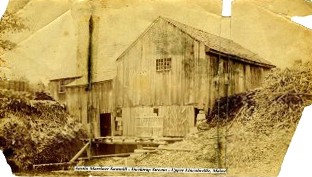

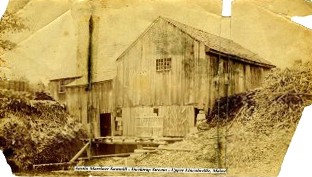

Austin

had a sawmill in the former Farmer’s

Pride District, now called the

Grange. He sawed out long lumber,

staves and barrel headings,

employing several local men. He

later sold his mill to Gould, who

had settled in the area.

Austin

had a sawmill in the former Farmer’s

Pride District, now called the

Grange. He sawed out long lumber,

staves and barrel headings,

employing several local men. He

later sold his mill to Gould, who

had settled in the area.

Austin

had heard about a movement that

started in the mid-western part of

the country, by an activist, Oliver

Hudson Kelley, called The Grange.

The theory of Kelley was that

farmers, scattered across the

Nation, needed a national

organization to represent them at

State and local levels. Farmers were

the backbone of the country, and

were being taken advantage of by

merchants, who would buy their

goods, and in turn sold them

supplies to keep their farms running

smoothly. The shipping companies

also took advantage of the farmers.

Kelley and

friends organized a fraternal group

called the Order of Patrons of

Husbandry, commonly called ‘The

Grange‘, taken from a Latin word

meaning grain or granary. Austin was

a enterprising, progressive farmer

who believed in the tenets of the

fledgling secret society.

Kelley and

friends organized a fraternal group

called the Order of Patrons of

Husbandry, commonly called ‘The

Grange‘, taken from a Latin word

meaning grain or granary. Austin was

a enterprising, progressive farmer

who believed in the tenets of the

fledgling secret society.

The

Granges began organizing in Maine,

about 1874. Mystic Grange in Belmont

organized and built a large hall and

Grange store in 1876. Farmer’s Pride

Grange in upper Lincolnville

organized about the same time, near

the Northport town line. Austin had

attended the local Granges. Farmer’s

Pride Grange had an active

membership, but had the misfortune

to have their hall burn in 1901.

Many of their members came from

Northport, making it more convenient

for them to join and attend the

Grange in that town.

Twenty-seven

of Austin’s neighbors and friends

met in the Old Town House on April

28th 1898 for the purpose

of organizing a Grange to be called

Tranquility, the 344th

Grange in the State of Maine. Austin

was installed as the first Master of

the Grange, an office which he held

in 1898, 1899 and 1900. Annie kept

the log book. A few of former

Farmer’s Pride members joined with

them.

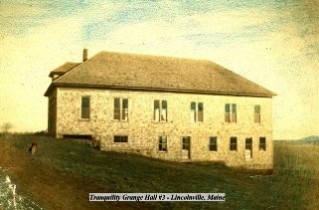

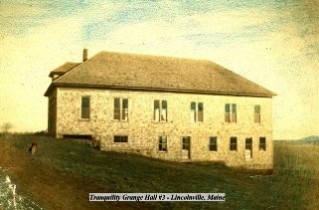

About

a years after organization,

Tranquility felt the need to have a

hall of their own. John C. and Eva

J. Dean, who lived down the road

from Austin, owned a piece of

property about a mile from the

Centre. They offered it to the

Grange for $50. The group raised

money, working and saving until they

had enough to start their own

building in 1903. It was a large

Gabriel-roofed building, which the

members were extremely proud of.

The

beautiful large hall was completed

in the late summer of 1904, having

volunteer material and labor, as

well as paid carpenters, with J. S.

Miller as the foreman. David McCobb

served as Master.

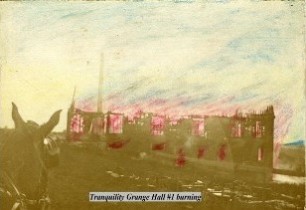

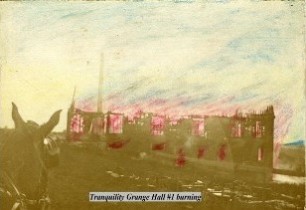

But their

joy was short-lived. The building

burned nearly to the ground. Arne

Knight, who lived close to the hall,

raced up bareback on his horse.

Others gathered at the scene.

Because the windows had only been

pegged in, the men braved the heat,

pulling out windows, chairs, tables

and benches. The Grange members were

just thankful that no one had been

seriously hurt in the conflagration.

But their

joy was short-lived. The building

burned nearly to the ground. Arne

Knight, who lived close to the hall,

raced up bareback on his horse.

Others gathered at the scene.

Because the windows had only been

pegged in, the men braved the heat,

pulling out windows, chairs, tables

and benches. The Grange members were

just thankful that no one had been

seriously hurt in the conflagration.

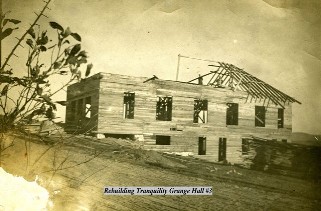

The

hardy group again met at the Town

House, where their meager building

materials were stored. Some wanted

to give up the idea of having their

own hall. Austin was among those who

vowed to press forward.

Once

again, after cleaning up the debris,

the stout-hearted group hired

carpenters and workers, as well as

volunteering as much of their time

as could be spared from the home

farms. The women kept the food

coming, with encouraging words.

Austin, Caroline, Annie and her

husband, Rich Lermond put in as much

time as possible It was late Spring,

and there was much to do at home on

the farm.

The

second building was smaller than the

first. The farmers could not spare a

lot of their hard-earned profits to

put back into the building. The hall

was nearly ready for the plasterers

to finish the inside, when the

unspeakable happened. On the 25th

day of May, 1908, came the word, the

Grange is burning. Tranquility was

not all tranquil. Austin and Callie

drove down to the spot where they

had all worked so hard for so long,

now just a pile of burning embers.

Austin’s heart was breaking, Callie

held back the tears. Their daughter,

Annie with her husband Richard, and

three little girls, Mildred, Callie

and Mary drove in behind them in

their buggy. Annie wept openly. It

had all seemed so fruitless.

This time

the fire was obviously of a

suspicious origin. All of the

evidence pointed to one of their

neighbors, and a relative of

Callie’s. Surely, no one could

dislike the group that much. The

case was taken to court, but

apparently nothing came of the

accusations.

This time

the fire was obviously of a

suspicious origin. All of the

evidence pointed to one of their

neighbors, and a relative of

Callie’s. Surely, no one could

dislike the group that much. The

case was taken to court, but

apparently nothing came of the

accusations.

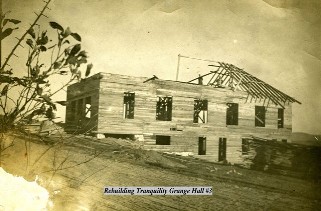

In

the early Fall of 1908, the

disheartening task of rebuilding

Tranquility Grange Hall commenced.

The carpenters and volunteer

builders worked through the fall and

winter. In January of 1909, the

beautiful new edifice was ready for

the hardy group to settle into.

Instead of plastered walls and

ceilings, the group had installed

lovely pressed metal. The ceiling

was domed with a striking metal

design which had been tastefully

painted with multiple colors.

Austin

was a member of the famed

Lincolnville Band, founded by Dr. B.

F. Young, who had been selling

organs at the time. Young, while

traveling about the countryside in

his business, had happened upon some

old brass instruments. Dr. Young was

very talented, teaching the young

men in his Youngtown neighborhood to

play, many of whom were Youngs and

Heals.

Austin’s

grandmother was Abigail Heal. He,

too, inherited some of the musical

ability. In 1879, they organized as

a band with fifteen members. As the

little band grew, they were called

upon to play for dances, political

rallies, and boating excursions.

They decided that it was time for

them to have uniforms. Around town,

many of the old Civil War veterans

had uniforms which they no longer

needed or wanted. They were modified

to fit the members. Now when they

played, they were all clad in classy

royal-blue uniforms.

The

Band was well received everywhere,

but never more so, as when they

headed up a Grand Army delegation,

playing at the Encampment in Boston

around 1890. Amasa Heal later wrote

abut the event, refreshing the

memories of those who attended. They

were the only band that sang as they

played and marched, receiving encore

after encore. There were eighty

bands present, some very large.

Lincolnville Band had seventeen

members attending that day.

When

they stopped before the President’s

stand and sang, “The Vacant Chair”,

the ovation rang through the

rafters, stealing the show, and

bringing them praise in the Boston

newspapers. Relatives and friends

from the Boston Area kept sending

them newspaper clippings about the

Lincolnville Band.

Austin

had joined and was a member in good

standing of the Mt. Battie Lodge, I.

O. O. F. in Camden, as well as his

Grange membership. Austin’s cousin,

Allen Miller, and he were both

active Democrats, attending the

State Convention in Augusta

together. They also attended

meetings of the State Grange there.

In

the Spring of 1915, Austin came down

sick with the influenza, from which

he never fully recovered. Effie

Dickey reported in her newspaper

column in 1916, “Like a bolt from a

clear sky came the news over the

phone on Wednesday, Feb. 9th,

announcing the death of Mr. Austin

Marriner, who sustained a shock on

that morning from which he never

rallied. His attending physician,

Dr. E. F. Gould, when called said

that death was but a matter of a few

hours, and he died at noon.”

She

also reported, “He was an honest and

upright citizen, strong in his ideas

and convictions, and no member of

the community could be more widely

missed. He was deeply interested in

all public and town affairs, and in

politics was a staunch Democrat.”

Austin’s

funeral was held in the home where

he had been born, lived his entire

life, and died. The funeral was well

attended with a display of beautiful

floral tributes. Rev. Sylvanus E.

Frohock officiated at the funeral.

Austin was laid to rest in the Union

Cemetery, where his parents, grand

and great-grandparents rested,

beside his beloved Callie, who had

died in 1905, at the age of

fifty-one years. He was sixty-nine

years of age, living life to the

fullest and making a difference in

the town settled by his forefathers.

Naler had

built a log cabin behind the present

house. The indentation was still

visible in the ground. The property

passed from Naler and Ruth Mariner

to their son Joseph Mariner, who in

turn passed it on the William and

Sarah (Jackson) Marriner. Austin had

inherited it from his father,

William, intending to pass it on to

a son, but that was not to be.

Naler had

built a log cabin behind the present

house. The indentation was still

visible in the ground. The property

passed from Naler and Ruth Mariner

to their son Joseph Mariner, who in

turn passed it on the William and

Sarah (Jackson) Marriner. Austin had

inherited it from his father,

William, intending to pass it on to

a son, but that was not to be.  Many of

the neighbors were related, all

descendants of the early settlers of

the town. Austin brought his bride,

Callie Clark, from down on Clark’s

Corner to the farm in 1873, after

being married by J. D. Tucker, Esq.

It was nine years before their only

child, Annie Maria was born. Austin

enjoyed teasing Annie, calling her

“Annie ‘Ria”.

Many of

the neighbors were related, all

descendants of the early settlers of

the town. Austin brought his bride,

Callie Clark, from down on Clark’s

Corner to the farm in 1873, after

being married by J. D. Tucker, Esq.

It was nine years before their only

child, Annie Maria was born. Austin

enjoyed teasing Annie, calling her

“Annie ‘Ria”. Austin was

an active farmer, planting crops as

well as many kinds of apple and pear

trees, which he took great pride in.

He made barrels in his cooper shop,

on rainy days, and in cold, wintry

weather. He shipped his apples and

farm produce on the Boston Steamers

for Massachusetts markets in his

well-made barrels. He also made

casks for the lime industry and his

own cider-vinegar production. Austin

himself was a temperance man, who

did not indulge in alcohol.

Austin was

an active farmer, planting crops as

well as many kinds of apple and pear

trees, which he took great pride in.

He made barrels in his cooper shop,

on rainy days, and in cold, wintry

weather. He shipped his apples and

farm produce on the Boston Steamers

for Massachusetts markets in his

well-made barrels. He also made

casks for the lime industry and his

own cider-vinegar production. Austin

himself was a temperance man, who

did not indulge in alcohol. Austin

had a sawmill in the former Farmer’s

Pride District, now called the

Grange. He sawed out long lumber,

staves and barrel headings,

employing several local men. He

later sold his mill to Gould, who

had settled in the area.

Austin

had a sawmill in the former Farmer’s

Pride District, now called the

Grange. He sawed out long lumber,

staves and barrel headings,

employing several local men. He

later sold his mill to Gould, who

had settled in the area. Kelley and

friends organized a fraternal group

called the Order of Patrons of

Husbandry, commonly called ‘The

Grange‘, taken from a Latin word

meaning grain or granary. Austin was

a enterprising, progressive farmer

who believed in the tenets of the

fledgling secret society.

Kelley and

friends organized a fraternal group

called the Order of Patrons of

Husbandry, commonly called ‘The

Grange‘, taken from a Latin word

meaning grain or granary. Austin was

a enterprising, progressive farmer

who believed in the tenets of the

fledgling secret society.  But their

joy was short-lived. The building

burned nearly to the ground. Arne

Knight, who lived close to the hall,

raced up bareback on his horse.

Others gathered at the scene.

Because the windows had only been

pegged in, the men braved the heat,

pulling out windows, chairs, tables

and benches. The Grange members were

just thankful that no one had been

seriously hurt in the conflagration.

But their

joy was short-lived. The building

burned nearly to the ground. Arne

Knight, who lived close to the hall,

raced up bareback on his horse.

Others gathered at the scene.

Because the windows had only been

pegged in, the men braved the heat,

pulling out windows, chairs, tables

and benches. The Grange members were

just thankful that no one had been

seriously hurt in the conflagration. This time

the fire was obviously of a

suspicious origin. All of the

evidence pointed to one of their

neighbors, and a relative of

Callie’s. Surely, no one could

dislike the group that much. The

case was taken to court, but

apparently nothing came of the

accusations.

This time

the fire was obviously of a

suspicious origin. All of the

evidence pointed to one of their

neighbors, and a relative of

Callie’s. Surely, no one could

dislike the group that much. The

case was taken to court, but

apparently nothing came of the

accusations.