Life

was looking brighter for Lester on that

crisp April evening in 1942. He’d had

a fine supper of dandelion greens, cooked

with pork fat and the fixings of good Maine

fare, prepared for him by his wife of seven

months.

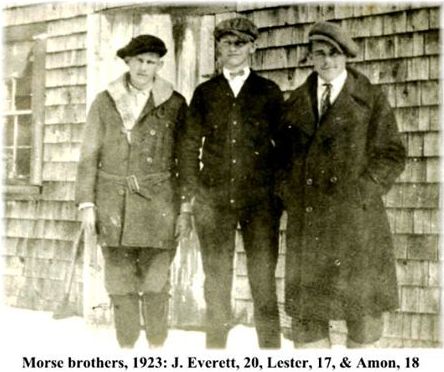

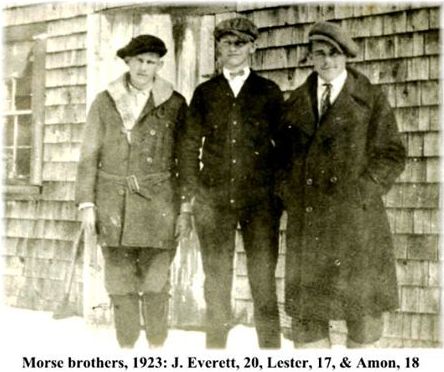

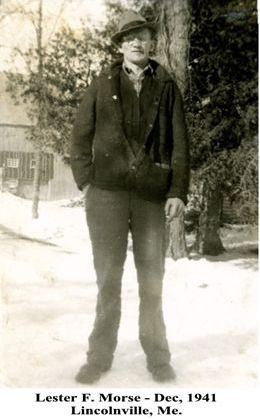

| Lester

Francis Morse was born in Belmont in

1906, the youngest child of John and

Jennie (Levenseller) Morse. He

was exactly one year and one day old

when his mother, Jennie, died while

giving birth to her eighth child,

who died a couple of days later.

Lester was very close to his

brother, Amon, who was fourteen

months older than he.

The boys, with their older

siblings were raised by their

hard-working grandmother, who was

also raising several motherless

cousins.

The boys learned early in life

that they had to work to partially

support themselves. Lester lived

for some time with Aunt Etta and

Uncle Fred Batchelder, doing farm

work to earn his board. As

he grew older, he worked on farms

in the Belmont, Belfast and

Searsmont area

|

|

| When

Lester was twenty-seven, he married

Annie Rogers of Searsmont. Annie had

older sisters who did not approve of

their marriage, as they thought that

he, being seven years older, was

much to old for her. They

considered him a ne’er-do-well,

though he worked at the Knox Woolen

Mill in Camden

When

Lester was twenty-seven, he

married Annie Rogers of Searsmont.

Annie had older sisters who did

not approve of their marriage, as

they thought that he, being seven

years older, was much to old for

her. They considered him a

ne’er-do-well, though he worked at

the Knox Woolen Mill in

Camden.

|

|

|

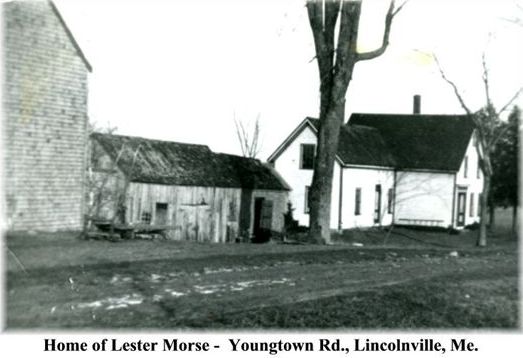

In

1935 Lester and Annie were

interested in buying the Ernest

Young farm in the Youngtown area of

Lincolnville, but didn’t have the

money. His brother, agreed to buy

the farm, giving Lester a mortgage.

They moved there with

daughters, Helen and Joan. The

twins were born at the farm.

Another

of life’s tragedies struck in the

spring of 1940. Annie had

been sick with an ear ache, which

they treated with home remedies.

She seemed better as Lester

went to work at the Woolen Mill.

The infection behind her ear

raged. Finally a doctor was called

to the home, where Annie died on

May third, aged about twenty-seven

years. Annie’s sisters never

forgave Lester for her

|

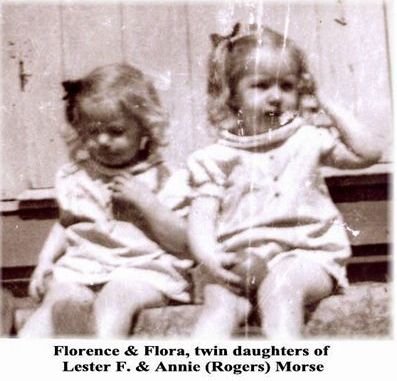

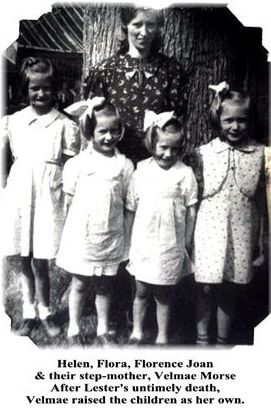

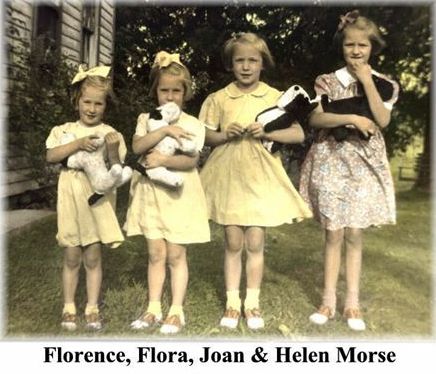

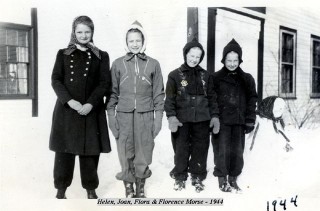

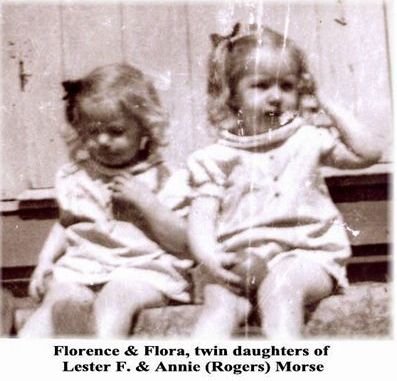

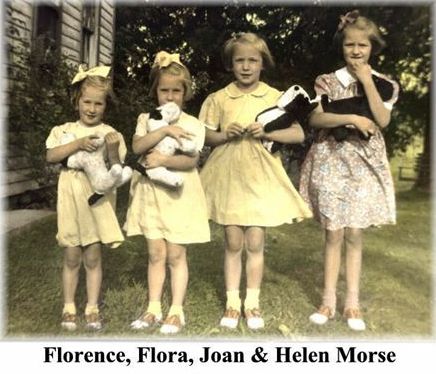

| Lester

was left to care for four motherless

daughters, Helen, six and a half

years old, Joan five and a half,

with the twins, Flora and Florence,

being four years old. Annie’s

sisters offered to take the girls

between them to raise, with no

interference from Lester. He was

adamant that the family be kept

together. He had a succession

of housekeepers, some of whom some

had marriage ideas, but he was not

ready to remarry. He was

feeling overwhelmed by his

responsibilities and quit his job at

the mill. |

|

It

has been a year since Annie’s death,

when he went to Camden to visit a

young woman that he had met from his

brother, Everett’s neighborhood.

He

went onto the porch of the

Kellett’s where Velmae Basford

worked and asked for her.Lester

told her that he wouldn’t make any

flowery promises, but that he

needed a housekeeper, a mother for

his children, and that he would

marry her. To the surprise of both

of them, she said “Yes”.

|

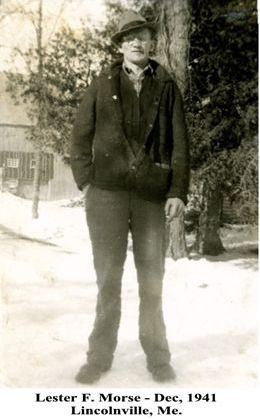

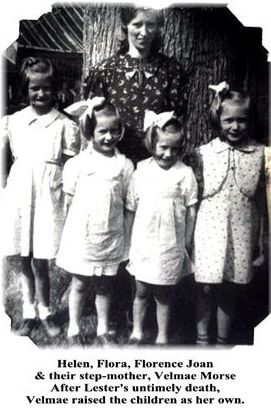

Lester

and Velmae were married in September 1941.

Velmae was good for the family.

Every morning she got the girls

dressed, combed and braided their hair,

and sent the two older girls off to

school. The girls didn’t have much

for clothing when she went to the farm.

She made them dresses, matching

panties, and whatever else they needed.

She and Lester had hatched out

chickens and built a henhouse across the

road, with a brooder stove to keep them

warm. At Christmas Velmae and a

neighbor, Trigger Carver, made life-size

rag dolls with a wardrobe of clothing, one

for each of the girls and Trigger’s

daughter.

|

Lester

and Velmae were married in

September 1941. Velmae was good

for the family. Every

morning she got the girls dressed,

combed and braided their hair, and

sent the two older girls off to

school. The girls didn’t

have much for clothing when she

went to the farm. She made

them dresses, matching panties,

and whatever else they needed.

She and Lester had hatched

out chickens and built a henhouse

across the road, with a brooder

stove to keep them warm. At

Christmas Velmae and a neighbor,

Trigger Carver, made life-size rag

dolls with a wardrobe of clothing,

one for each of the girls and

Trigger’s daughter.

|

|

On the evening of April 1942, Velmae had

cleaned up the dishes after supper, put

the girls to bed, and was darning socks in

the living room, while listening to the

grammerphone that she’d brought with her

when she came to Lester’s home. He told

her that he was going next door to Clyde

Young’s to make a phone call to George

Hardy about a carpenter’s assistant job.

Velmae looked out of the window and saw

Lester standing in the road in front of

the house, talking to a man that she

didn’t recognize. She stepped to the

door and heard Lester say, “I’ll be right

with you.”

Sometime later, Clyde came to the house

and asked where Lester was. She

answered that she supposed he had gone to

Clyde’s house to use the phone.

Clyde said that he hadn’t seen him,

but there was a huge fire in the vicinity

of Leigh Richards’ barn.

Velmae went to check on the chicks.

She fretted that if the fire spread,

they’d lose the brooder house, chickens

and all they’d invested. And where

was Lester?

The dirt road was muddy, as happens in

Maine in the Spring. The fire trucks

got bogged down in the mud. The

Camden and Lincolnville trucks were within

sight of the fire, but they couldn’t get

through. The neighbors tried a

’bucket brigade’, to no avail. The

barn burned to the ground.

The next morning, Everett went to Amon’s

in Northport to tell him that Lester

hadn’t come home. There were few

phones in the area at that time. The

night before, Amon has seen the fire from

Northport, and had started to go to

Youngtown, getting as far as Leigh

Miller’s. Those who had the old

crank phones has passed the news from one

house to another that Leigh Richards’ barn

was burning in Youngtown, so Amon turned

back.

In the morning, family members in

Lincolnville, Northport and Belmont

arrived at the Youngtown road searching

for Lester. They found the contents

of his pockets, a pencil, a small notebook

and other items along the road. Lester was

a tall, wiry man. To the family, it

appeared as though he had been thrown over

someone’s shoulder and carried, losing the

pocket contents. The cellar of the

old barn next door was still burning.

Richard Morse, with the curiosity of

youth, peered into the burning remains,

and thought that he saw a calf in the

smoldering barn cellar. He called

out to the adults, who determined that it

was the remains of a person.

Amon went to tell Velmae that Lester had

died in the fire. She didn’t

remember much after that. Mr. and Mrs.

Kellett from Camden came and took her to

their house. She said that she didn’t know

what ailed her. She was led around

and did as she was told. The house

and children were Lester’s. Her

world was shattered. What was she to

do, and where was she to go?

Lester’s siblings all had families of

their own, yet the family did not want to

see the girls separated, or to be sent to

the Girls Home in Belfast for orphans.

Velmae loved the girls and they

loved her.

Everett was appointed guardian of the

girls. All of Lester’s siblings

helped in their own way, giving whatever

assistance they could spare. They

were of farming families, in a farming

community, struggling from the

after-effects of the Depression. World War

II had started. Amon told Velmae that if

she would stay on and raise the girls,

that he would destroy the mortgage, and

the farm would be hers.

Dr. Vickery was called, and pronounced

that the death of the person was a

suicide, a story which the local

newspapers reported as front-page news.

Lester had worked for a doctor in Camden,

who said that he would never have

committed suicide. He got permission

to have his body exhumed for an autopsy,

which showed what he had eaten for supper,

and that he had consumed a large amount of

alcohol. The alcohol was a mystery

to the family. The gunshot wound had

entered from the back of his head.

The remains of a gun found in the

ruins, six feet from the body, was a

single barrel 12-gauge shotgun, which was

pried open to reveal that it contained a

16-gauge shell, impossible to shoot.

Lester had passed three vacant

buildings from his house to the barn which

he was found.

The investigating officers came to his

house, asking Velmae if Lester had a gun.

She replied that he only had one, going to

the closet and producing it. The

death was considered a suspected homicide.

Lester’s siblings never accepted the

verdict that he had taken his own life.

He had so much to live for, and his

life was on an upward turn. It was

wartime, four months after the Pearl

Harbor attack, making a nervous

neighborhood. There were tales that

it had something to do with the War, that

perhaps some of the Germans in submarines

between Lincolnville and Islesboro had

committed the deed. There were many

theories abounding throughout the family

and neighborhood. Officers at the time

told family members that they knew who had

committed the murder, but never could

prove it.

| Velmae

lived up to her promises to Lester,

to his family, and to herself.

She was a mother to the girls

for the rest of their lives, fully

devoting herself to them. She raised

chickens, did sewing, kept a clean,

healthy home, and was the only

mother that they had known. |

All

these years later, the murder of Lester

Frances Morse was never solved, and is

lost somewhere in police files. His

siblings, his widow, Velmae, and three of

his children are all gone, yet for some of

his nieces, nephews, daughter and

grandchildren, there is a nagging

wonderment about what happened in the

Youngtown neighborhood of Lincolnville,

Maine on that long-ago night of 7 April

1942. The perpetrator or

perpetrators have probably gone to their

reward also. The mystery of an unsolved

murder in Lincolnville, Maine remains.

|