Suse

brushed away a tear as she rocked in

her old chair at Etta’s home in

Searsmont. She longed to go home,

but apparently it was not to be. How

she loved that old house in Belmont.

What stories she could tell, if

anyone wanted to hear them. No need

to feel sorry for herself.

Suse

brushed away a tear as she rocked in

her old chair at Etta’s home in

Searsmont. She longed to go home,

but apparently it was not to be. How

she loved that old house in Belmont.

What stories she could tell, if

anyone wanted to hear them. No need

to feel sorry for herself.

She

thought back over the years that had

passed, oh, so quickly. She was

nearing eighty-seven years of age,

and couldn’t believe how fast the

years had flown. Mose had been gone

for twenty-two years now. How she

missed him! So many of her loved

ones had passed away to the other

side.

Suse

had been born in 1836 as Susan Marie

Shea in the “Keag’, South Thomaston,

Maine. She had learned early in

school that her home had been part

of the town named by the Indians,

“Wessaweskeag”, which people through

the years has shortened to “Keag”.

But most people just said that they

lived in the ‘Gig’.

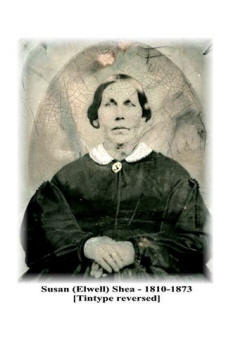

Suse

had been named after her mother,

Susan (Elwell) Shea. Her father,

John Shea, was of Irish descent.

Looking back, it seemed to Suse that

grief had followed her all of her

life. Suse was born as the first

daughter in her family having one

older brother. When she was twelve

years old, her fourteen-year old

brother, William, drowned in New

York Harbor, running a ‘warp’ line

from the schooner ‘Coral’

on which he was working, to a wharf

where he was overrun by another

schooner.

The

Indians were numerous in South

Thomaston, coming to the Coast to

fish. Suse had become friendly with

some of the tribe. As a young girl,

Suse yearned to know more about

healing and care of the sick and

aged. Her friendship with the

Indians allowed her to observe, to

question, and to learn the natural

healing ways. They had taught her

about healing herbs, how to pick and

preserve them, and how to make

medicines.

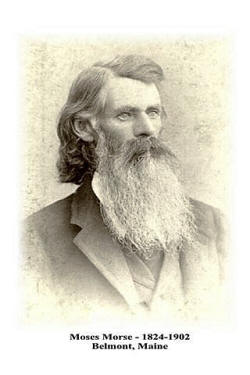

One day she spied a

blond white man among the group.

Suse recalled that she thought the

man, whose name she had learned was

Moses Morse, to be quite attractive.

He had come down with the Indians

from a town that she’d never heard

of, called Montville. She often

appeared on the shore at the same

time that Moses did. Their

friendship blossomed, so much so

that they took out marriage

intentions on Valentine’s Day, 1855.

In

the early days of their marriage,

Suse and Mose, as she called him,

lived in Belfast, where Mose had a

job working in the carriage shops,

where fine-quality carriages were

manufactured. Frederick Horace was

born in Belfast in 1856. Frank Alden

was born after they had moved to the

Moody Mt. Road in Searsmont. Mose

had farmed and fished in Montville,

where his mother still resided.

There was a farm in Belmont owned by

Widow Susan Poor, which they

purchased. Their first winter in

Belmont, the widow and her daughters

shared part of the house. They

worked hard, paying off the farm,

receiving the deed in April 1867.

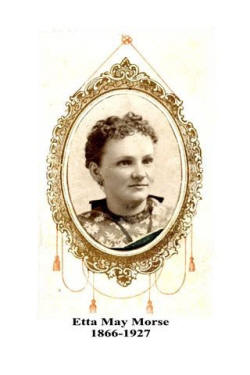

Etta May, John Wilbur and Ada Laura

were born after the move to Belmont.

Moses

traveled back and forth from the

farm home in Belmont to his widowed

mother’s home in Montville. Mose’s

father, John Lane Morse, had been

active in the fledgling town of

Montville, serving in several town

offices when he was struck down in

the prime of his life, and died at

the age of forty-six years. Suse was

never quite sure what his cause of

death had been. Mose, being the

youngest son, was devoted to his

mother and younger sisters. He would

get her firewood out, fit up the old

house for winter, and prepare, plant

and harvest her garden in season. He

felt obligated to keeping his mother

comfortable, until his eldest

sister, Eunice, took her to live in

Belfast with her and her husband,

John Cochran. Their aged mother,

Betsey Hannah Morse, died in Belfast

in April 1873, aged ninety-one

years.

Fred

and Frank had gone to Massachusetts

as they came of age, to make their

fortunes. Frank returned to Maine to

live. Suse had purchased three

sewing machines for her and her

daughters, making vests for a

wholesale company which engaged farm

women to earn supplemental income.

Mose was a carriage-maker by trade.

He also made fine-quality barrels in

his cooper shop, as well as lime

casks for the lime industry in

Rockland, and other coastal towns.

Mose

was known far and near as a

horse-trader and dickerer, as well

as being a farmer and cooper. Suse

chuckled to herself as she

remembered how exasperating Mose

could be in his dickering habits.

She recalled when his mother passed

away, Mose had taken one of his

horses to Halldale in Montville to

meet with his elder brothers,

Kendrick and Ezekiel, and Kendrick’s

son, Thomas, who had come down from

Detroit, Maine to dispose of the

property.

Until

she moved to Belfast, their mother

had lived in the old log cabin built

by her husband many years before. It

had been modified to make a

comfortable home for her, but since

she’d left to live with Eunice, it

had become very ramshackled, to the

point that it was falling down. The

floors were about gone, but Mose

stayed in the cabin for nearly a

fortnight while they settled things.

When

Mose had moved to Belmont, he had

taken his livestock, and most of the

machinery that he’d kept in repair.

There was little left on the old

farm, but he dickered and traded

with the neighbors with the

remainder of the estate. His

brothers had profitable farms to the

North, and it was left for Mose to

clean up the farm, which they sold

to a neighbor, Asa Hall. Mose loaded

up an old hay wagon with the

remnants of tools, machinery, and

household goods, hooked a pair

horses to the wagon, tied three more

horses behind that he’d dickered for

and headed for Belmont. On the way

home, he was asked by an old

neighbor who had seen him arrive

with one horse, “Mose”, where did

you get those horses?” to which he

replied with a wink of his eye,

“Never ask an Indian where he got a

horse!” Suse had welcomed him home

with open arms, but had been more

than a little upset at him for being

gone so long, causing her worry.

Suse

brushed away another tear, as she

recalled that her young sister,

Elvira Jane had died in 1865, at the

‘Gig’, at the age of twenty-one.

Because of the distance, Suse hadn’t

seen much of her family since she

had married. Tragedy seemed to

follow the family.

Word came

up from South Thomaston in 1873 that

her mother had passed away. Oh, how

Suse missed her mother! It didn’t

help much that Father had remarried

to Mary Ann (Clark) Atwood,

seventeen years his junior. After

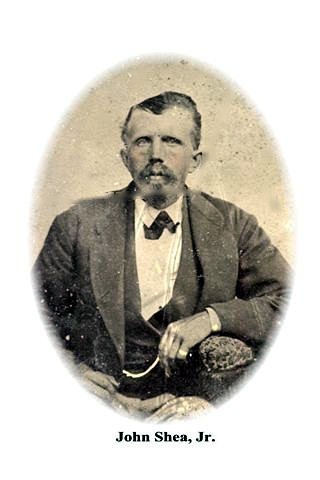

Father’s marriage, Suse’ brother,

John Shea, came to Belmont to live

with her and Mose. John and Mary Ann

just did not get along.

Word came

up from South Thomaston in 1873 that

her mother had passed away. Oh, how

Suse missed her mother! It didn’t

help much that Father had remarried

to Mary Ann (Clark) Atwood,

seventeen years his junior. After

Father’s marriage, Suse’ brother,

John Shea, came to Belmont to live

with her and Mose. John and Mary Ann

just did not get along.

One

year later, in 1874, her brother,

Frederick, died in Hallowell, Maine.

He was twenty-one years old. Father

told Suse that a Whip-poor-will, a

nocturnal bird associated with

predicting death, sang all night

when Frederick died. It was a

superstition that Suse believed in.

A

year and a half after Frederick’s

death, his twin sister, Ada Laura

Bachelor, died from complications of

childbirth, at age 22. She had only

been married two and a half years.

It seemed that the Shea family was

falling apart.

Then,

once again, in March 1884, a letter

came up from South Thomaston that

Father had died. The letter informed

Suse that she would have to come to

South Thomaston to sign papers, to

settle the Estate for Father’s

younger wife. Her son, twelve-year

old John, harnessed the horse and

hitched him to the sleigh. It was

early Spring, and the highways were

still packed with snow, as they

drove down through Lincolnville

Centre, over the turnpike to Camden,

through Rockland on to South

Thomaston, with sleigh-bells ringing

in the crisp, cold air. It was quite

a rode for the young man and his

mother.

On

arriving at Father’s old home, the

Probate lawyer met with them, and

told Suse that it was not only she,

but her brother, John, would have to

sign the papers. Young John took the

route back, pushing the horse as

hard as he dared. He then harnessed

up a fresh horse, got Uncle John

onto the sleigh, and back to South

Thomaston they went. It was a trip

that he never forgot.

Suse’s

son, Fred, who had gone to

Massachusetts to make a living, had

a successful Ice Dealer business,

delivering ice to homes for

refrigeration in the kitchen ice

boxes, as well as to stores and

businesses with greater ice needs.

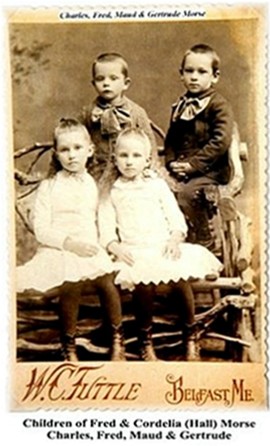

Fred married in May of 1879 to

nineteen-year-old Cordelia Hall,

daughter of Edward and Eunice Hall.

They soon were the parents of Maud,

born 1880, Gertrude, born 1881,

Fred, Jr., born 1884 and Horace born

1885. Then tragedy seemed to follow

Fred and it had over the years to

Suse. She received word that Fred’s

ten-month-old baby, Harry died in

September 1888. Charles and a

stillborn twin were born two months

after Harry’s death. Charles was not

quite three months old in February

1889 when Fred’s wife, Cordelia also

died. She had never rallied from the

hard childbirth, and was but

twenty-eight years old.

Suse’s

son, Fred, who had gone to

Massachusetts to make a living, had

a successful Ice Dealer business,

delivering ice to homes for

refrigeration in the kitchen ice

boxes, as well as to stores and

businesses with greater ice needs.

Fred married in May of 1879 to

nineteen-year-old Cordelia Hall,

daughter of Edward and Eunice Hall.

They soon were the parents of Maud,

born 1880, Gertrude, born 1881,

Fred, Jr., born 1884 and Horace born

1885. Then tragedy seemed to follow

Fred and it had over the years to

Suse. She received word that Fred’s

ten-month-old baby, Harry died in

September 1888. Charles and a

stillborn twin were born two months

after Harry’s death. Charles was not

quite three months old in February

1889 when Fred’s wife, Cordelia also

died. She had never rallied from the

hard childbirth, and was but

twenty-eight years old.

Fred

struggled to raise his children. He

married Isabella Grant in 1890. When

nine-year-old Horace died in 1895,

and Isabella also passed away, Fred

wrote to his mother, asking her if

she would come to Massachusetts to

bring the children back to the farm

in Belmont.

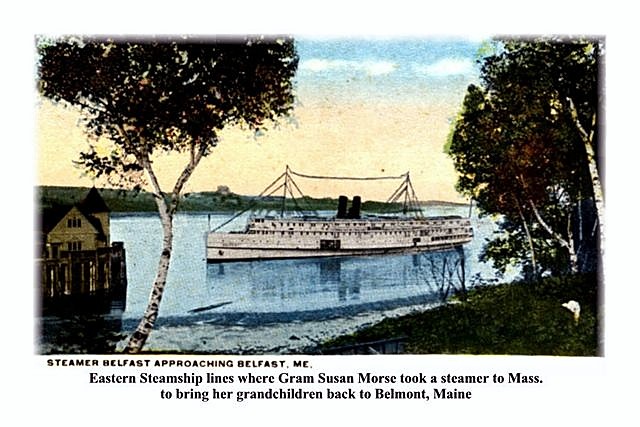

Suse

recalled that she got on one of the

Eastern Steamship boats in Belfast,

traveling down the coast to Boston,

where Fred met her. He took her to

his home in Jamaica Plain. She

gathered together four small

children, who did not remember their

grandmother, with the meager

collection of clothing, cloth

diapers, milk for the baby, and once

again boarded the Steamer to go

home. She remembered thinking that

when she got them back to the farm,

there would be plenty to eat with

fresh milk and vegetables for the

youngsters.

Suse

recalled that she got on one of the

Eastern Steamship boats in Belfast,

traveling down the coast to Boston,

where Fred met her. He took her to

his home in Jamaica Plain. She

gathered together four small

children, who did not remember their

grandmother, with the meager

collection of clothing, cloth

diapers, milk for the baby, and once

again boarded the Steamer to go

home. She remembered thinking that

when she got them back to the farm,

there would be plenty to eat with

fresh milk and vegetables for the

youngsters.

The

little ones were apprehensive, and

were sick all of the way back to

Belfast. It could have been

seasickness, or just the nervousness

of traveling with an unknown

Grandmother, to an unknown farm in

Maine, without either parent. They

clung together. They were Maud,

Gertrude, Fred Jr. and little

Charles. There was no time to

grieve. Children need care.

Suse’s

daughter Ada, who had been named

after her sister, Ada Laura, married

Ed Howard, who lived next door to

the farm in Belmont. Ada and Ed’s

firstborn son was born prematurely.

He died a week after his birth in

March 1895, about five weeks after

Horace’s passing. Two beautiful

babies gone in such a short time!

Ada had two more sons, Edward

‘Colby’ and Dudley.

On

Valentine’s day, 1895, John married

seventeen-year old Jennie

Levenseller, bringing her home to

live, with the boisterous household.

It was ten days after John’s

marriage that Fred’s nine-year old

son, Horace died. John and Jennie’s

family quickly grew.

Frank

had married Nettie Whiting from New

Hampshire. He and Nettie also had a

growing family, William, Frank, Jr.,

Georgia, David Raymond, who died in

1896, aged 2 months, and Ruth. As

Suse rocked, recalling her full

life, she was amazed at just how

much tragedy she had lived through,

as well as the joys of life. .

Etta

married Fred Batchelder in 1884.

Fred had always been good to Suse.

Etta and Fred had four daughters,

Susie Marie, named after her

grandmother, Laura Margene, Julia

and Lottie Etta. In January of 1902,

Etta’s eight-year-old daughter,

Julia, died of ‘toxemia’. Etta

grieved for little Julia for the

rest of her life. Laura married

Irvin McFarland, whose only infant

son, Walter died in 1909, aged three

months.

Etta

married Fred Batchelder in 1884.

Fred had always been good to Suse.

Etta and Fred had four daughters,

Susie Marie, named after her

grandmother, Laura Margene, Julia

and Lottie Etta. In January of 1902,

Etta’s eight-year-old daughter,

Julia, died of ‘toxemia’. Etta

grieved for little Julia for the

rest of her life. Laura married

Irvin McFarland, whose only infant

son, Walter died in 1909, aged three

months.

Suse’s

son John had told her that his

father, Mose, had confided to him in

early March, 1902, that he was

dying. Mose had developed

tuberculosis, and Suse was aware

that he was not doing well. Mose,

who had been working at the Chenery

farm in Belmont, had walked home for

dinner. He was nearly eighty years

old, but even at his advanced age,

he had been supervising the building

of a stone drainage walls at

Chenery’s on a hot March day. Mose’

age and expertise were appreciated

by Horace Chenery, as he rebuilt and

improved the stone walls on his

property.

Several

of the children were gathered around

the dinner table, including Frank’s

four-year-old daughter, Ruth. As

they enjoyed the home-cooked dinner,

with the chatter that comes from a

bunch of children, Ruth called out

to Suse that Grampa’s head had

dropped down, and he was sleeping.

Suse checked on Mose, who was not

sleeping, he was dead. It was the

twenty-second day of March.

Suse’s

brother, sixty-one-year old John,

had been a great help to her after

Mose’s death. He did the barn and

outside chores, as well as assisting

the boys in keeping firewood in the

wood box. In the Fall, when he had

been helping his nephew, John, chop

firewood in the back woods, a limb

came down, striking him on the head.

He had a bad gash, which Suse

dressed and tended. The wound seemed

to be healing well, as he continued

with the outside work. He enjoyed

sitting on the front step in the

sun, taking in the beautiful scenery

of the twin Levenseller Mountains

across the field. Then Brother John

became sick, and his jaw and muscles

were very painful. He had developed

tetanus, most commonly called

‘lockjaw‘. John suffered much,

passing away in January of 1903,

less than a year after Mose had

died.

In

1906, Frank’s daughter,

twelve-year-old Georgia, married her

fifteen-year-old boyfriend, Frank

Dickey. Suse shook her head, all

these years later, at the young

marriage. It was three years before

Georgia and Frank had children,

Clifton and Vesta.

Fred,

Jr., one of the children that Suse

had brought back from Massachusetts,

married Emma Kent from Rockport,

Maine. Their first daughter,

Clorinda Cordelia, named after his

mother, died in Jan. 1906, at the

age of ten months. They eventually

raised a large family, Marion, Maud

Evelyn, Susan Marie, Leona, Mildred,

Laura, Fred, Arlene, Charles, Ethel,

Virginia And Rodney.

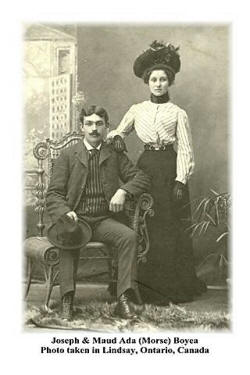

Fred

Jr.’s sister, Maud, who had married

Joseph Boyea and moved to Lindsay,

Victoria [South], Quebec, Canada,

died in July of the same year of

childbirth complications, leaving a

three-year-old daughter, Catherine.

Suse never saw Maud after her

marriage.

Fred

Jr.’s sister, Maud, who had married

Joseph Boyea and moved to Lindsay,

Victoria [South], Quebec, Canada,

died in July of the same year of

childbirth complications, leaving a

three-year-old daughter, Catherine.

Suse never saw Maud after her

marriage.

Gert,

the second daughter of Fred, married

Edgar Marriner. They had a large

family, Katherine, Avis, twins,

Edgar and Evelyn, three-week old

Etta, who died in 1907, Charles

Kenneth, Leverne, Clifton, Hattie

Irene, five-month old Horace who

died in 1913, an unnamed baby in

July 1917, and Madelyn Marriner.

John

and Jennie’s family was growing.

Susie, named after her grandmother,

was born in 1895, followed by

Bertha, Hazel, Clarence, Everett,

Amon and Lester. In 1907,

thirty-year-old Jennie was expecting

her eighth child. Jennie was

underweight and pale. She’d had some

problems during her pregnancy. She

was six to seven months pregnant in

July, when she went into labor. She

bled profusely. Suse had always been

called out as a midwife in the

neighborhood, but she didn’t like

the progression of Jennie’s

delivery. The infant son was born on

the seventh of July. Jennie didn’t

rally, as life seemed to drain from

her, and she passed away two hours

after delivery. The tiny motherless

baby struggled for life, and died

the eleventh of July, on the day

that Jennie was buried in the family

plot in East Searsmont, about two

miles from home. A grieving John and

some of the neighbors tearfully

carried the small bundle back to the

cemetery, burying him in his

mother’s arms.

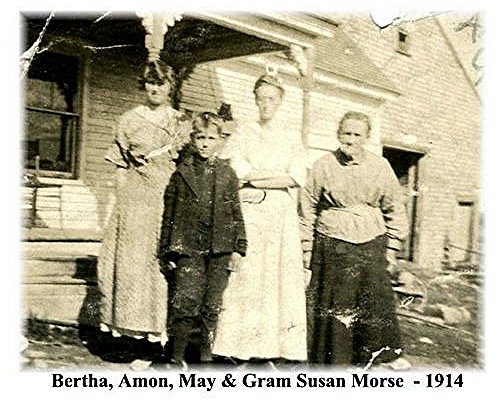

Suse

dozed a bit in her chair, recalling

that Amon, who was but two years old

when his mother died, had polio, as

did Ada’s son Dudley. Suse was

determined to have the boys walking,

but Ada thought that the treatments

were too harsh. Suse would have

Clarence and Everett walk Amon

around the home and yard, until he

would beg to sit down. The treatment

apparently worked for Amon, as he

eventually walked. Dudley did not

fare so well, and was crippled all

of his life, as his case was much

more severe.

The older

boys worked in the woods with their

father, John. Because of Amon’s

condition and age, he spent many

hours with Suse and his younger

brother, Lester. Suse told the boys

many stories of her youth, of her

family, and of all of the children

who had come and gone in the old

house. She would take the boys, Amon

and Lester, into the woods behind

their home, to gather herbs, roots

and plants for medicinal use

throughout the year. It was the

practice that she was taught from

the Indians of her youth.

The older

boys worked in the woods with their

father, John. Because of Amon’s

condition and age, he spent many

hours with Suse and his younger

brother, Lester. Suse told the boys

many stories of her youth, of her

family, and of all of the children

who had come and gone in the old

house. She would take the boys, Amon

and Lester, into the woods behind

their home, to gather herbs, roots

and plants for medicinal use

throughout the year. It was the

practice that she was taught from

the Indians of her youth.

John’s

young daughters had a friend, Mary

Elizabeth Butler, who lived across

the woods in Searsmont. The girls

visited back and forth, with the

girls having sleep-overs at each

other’s house. A little over a year

after Jennie died, thirty-six-year

old John married fifteen-year-old

May, as she was called. Suse told

the children that John had brought

home another child for her to care

for.

One

of the greatest losses that Suse

recalled, was of Fred’s son,

Charles, that she had brought back

from Massachusetts. Charles had

always lived with Suse and Mose,

being three months old when his

mother died. He had been a very

loving child, being very close to

his grandmother. He had not been as

strong as the other children, and

was just a small child when he came

to live with them. Charles developed

the dread disease, tuberculosis,

suffering from the effects of the

disease. Charles told Suse that he’s

seen the trees leave out in the

Spring, but he wouldn’t see them

fall. Charles slept in the cold open

bed-chamber over the kitchen. He was

twenty-one years old when he

succumbed to the disease in June

1910.

As

Suse rocked in the old chair, it

seemed to her that death had been a

frequent visitor to the Morse home.

She contacted her niece’s husband,

Hollis Rackliff, and ordered a

gravestone for the family plot in

East Searsmont. He brought up a

large ornate marble gravestone,

hauling it all of the way from South

Thomaston with a team of horses. He

had engraved the names of Moses,

Jennie, John, as well as her own

name and birthdate on the face of

the monument. Charles’ name was

engraved on the back. It won’t be

long now, she thought, until she

would be interred with those that

she loved so much.

Two

years after Charles died, Frank’s

wife, Nettie, passed away from

pneumonia. Suse could see in her

mind’s eye, a row of gravestones of

her family. The family monuments had

come up from South Thomaston.

In

all of life’s tribulations, Suse had

always felt safe in the comfortable

old farm home. Then one day in

March, 1913, John and May had taken

a load of lime casks that John had

made in his cooper shop to Rockland.

The children, including John and

May’s three-year-old daughter,

Faustena, were home with Suse when

someone smelled smoke. Many, many

years later, Faustena told her

grandmother that she’d been playing

with matches in the bed-chamber over

the kitchen, dropping one down by

the crack in the chimney. Faustena

was angry because she was not

allowed to go with her parents to

Rockland. Her grandmother did not

believe that she was old enough at

the time to have done such a deed.

In

all of life’s tribulations, Suse had

always felt safe in the comfortable

old farm home. Then one day in

March, 1913, John and May had taken

a load of lime casks that John had

made in his cooper shop to Rockland.

The children, including John and

May’s three-year-old daughter,

Faustena, were home with Suse when

someone smelled smoke. Many, many

years later, Faustena told her

grandmother that she’d been playing

with matches in the bed-chamber over

the kitchen, dropping one down by

the crack in the chimney. Faustena

was angry because she was not

allowed to go with her parents to

Rockland. Her grandmother did not

believe that she was old enough at

the time to have done such a deed.

The

main attic of the house was all

afire. The neighbors formed a bucket

brigade, which had little effect on

the fast-moving fire. They brought

in teams of horses and oxen, with

which they pulled the ell and

woodshed off from between the house

and the barn. With the aid of a

growing group of neighbors, with

more buckets of water, the barn was

saved, though badly scorched. Suse

recalled that barrels from the

cooper shop across the road were

dragged into the house. In the

excitement, dishes were thrown into

barrels, and the barrels thrown out

of the windows, breaking their

contents. Pictures were grabbed from

the walls and saved. Most of the

household goods were destroyed.

Amon, Lester and Faustena were taken

to Ada’s where they stayed with

Dudley. Thankfully, there was no

loss of life.

Suse

kept busy as neighborhood midwife.

She was called to “lay out the dead”

for burial, and was even

occasionally called by Dr. Tapley of

Belfast to do home operations,

sometimes on the kitchen table of a

home. Suse was well-known as an

herbal nurse, a trade she had

learned from the Indians of her

youth at South Thomaston.

Fred,

Jr. and Emma had moved his family of

eight up from Rockport, Maine,

bringing all of their belongings on

a hay rack. They arrived in Belmont

after dark, spending their first

night at the farm with Suse and all

of the resident children. Faustena

entertained all of them well into

the night, singing, “It’s a long way

to Tipperary!” Fred Jr.’s daughter,

Evelyn, emphatically told Suse that

Mama said that babies came in the

doctor’s black bag. The next day

Fred and Emma moved their family

down to a little house owned by his

father, Fred, Sr., across from

Greer’s Corner Schoolhouse.

All

of the neighborhood children

attended the one-room Greer’s Corner

School. Clarence came home one day,

and told Suse how he had played

Santa Clause at the Christmas party.

He had red clothes and a cotton

beard. As he bent over a candle, his

beard caught fire. Fred Jr.’s little

ones were dumb-founded as they ran

home and told their mother that

Santa Clause wasn’t Santa Clause,

but was cousin Clarence.

Suse

recalled the day the Fred Jr.’s

older children, then only eight and

ten years old, came up across the

field to tell her that Emma needed

her to come down quickly. Clarence

harnessed the horse, helped Suse on

to the pung, with the children

piling on the back, and driving her

down to Fred Jr. and Emma’s home.

The three-week-old baby, Charles

Bradford, was dead in his make-shift

crib. The children were not even

aware of what was going on, but for

the rest of their lives, remembered

the pounding of a hammer as a small

coffin was made from a strawberry

crate. The baby was buried in the

back yard, with Suse saying a few

words over the tiny grave. A few

days later, the Town officials came

to the door, telling the family that

the baby’s death had to be recorded,

and that he should be buried in the

family cemetery plot. These many

hears later, Suse’s memory was

sometimes blurred. She didn’t recall

if little Charles was buried with

his uncle of the same name in the

family plot in East Searsmont, or if

he was still buried on the home

farm. She thought that he had been

buried on the back side of the

cemetery plot.

John’s

young wife, May, had been a doting

mother, taking Faustena everywhere

she went. She sold Larkin soap to

the neighbors, to earn points for

prizes. May earned several pieces of

furniture, one of which was a Larkin

drop-leaf desk. She also

commissioned an artist to do a large

framed portrait of John, taken from

a 1911 photo, in which John had

served on the Waldo County Superior

Court Jury.

May

also developed tuberculosis, with

the symptoms of bleeding, coughing

and strangling for breath. She slept

nights on the cold ground under the

apple tree, waiting for John to come

home. She also slept on the cold

porch during the winter months. Suse

believed that cold air was

beneficial to those suffering from

the disease. It may have helped the

strangling cough.

Suse

could see that May was failing. One

night John told Bertha to wake

twelve-year-old Amon to harness Dan,

the horse, to take the wagon to

Searsmont to bring May’s mother,

Martha Butler, back to be with her

daughter. Amon had a way with the

spirited horse. Amon later told Suse

that it was a wild ride to

Searsmont, as he held the lantern to

light the way. Martha was a large

woman, and Amon recalled that they

had difficulty getting her into the

wagon. That night, in June of 1917,

nearly ten years after Jennie had

died, twenty-three-year old May

died, leaving seven-year-old

Faustena without a mother. May was

buried in the family plot in the

cemetery in East Searsmont. Suse

regretted that she had never gotten

around to place a marker on the

young bride’s grave.

Fred

had married a third wife, Susan

Lincoln Nichols, by whom he had

three daughters, Emily, Marion and

Dorothy. They were living in Malden,

Mass. Suse never met Fred’s new wife

and children. Four months after

May’s death, Suse received word from

Massachusetts that her eldest son,

Fred, had died in October, 1917 at

at Boston, Mass. Hospital, aged

fifty-seven years. .

Suse

was often called out to tend the

sick. In 1917 and 1918 the flu

epidemic was raging. News came to

the vicinity that hundreds of

soldiers were dying at Fort Dix, New

Jersey. John’s daughter, Bertha, had

been boarding with George and Carrie

Sylvester, working at a restaurant

in Belfast when she contracted the

flu. She came home to Belmont to her

grandmother, Suse, to take care of

her. Bertha got progressively worse,

and died at home, in November 1918,

not quite twenty-two years old.

Suse

remembered the sad day in 1919 when

news came that her great-grandson,

Arnold, the five-year-old son of her

grandson Will, had been run over by

an electric car in front of the

school in Portland. The boy had been

playing in the playground across the

tracks from the school. When the

afternoon bell rang, in his haste to

get to the school, he slipped and

fell on the tracks as the electric

car passed. His legs were nearly

severed. He was taken to the

hospital and died before his mother

and father arrived. Will had been an

engineer on the railroad, working

and living in Portland.

So

much tragedy, and it seemed that it

just continued. The influenza

epidemic raged on. In February of

1920, Fred, Jr.’s four-year-old

daughter, Arlene, died of the flu.

Fred, Jr., who had been working in

the quarries in Rockport, Maine,

also had the flu. Three days later,

word was sent to Suse that Fred, Jr.

had died of the disease.

Suse’

son, John, married for the third

time in April 1922 to Cora McFarland

Vose. He left the family farm and

moved to Knox to live on Cora’s

large farm. John’s daughter, her

namesake, Susie, had married Jephtha

Buck in 1912. Jephtha and Susie

lived with John’s family and Suse on

the farm. Gram Suse had spent her

lifetime taking care of children,

tending to the sick, rejoicing in

the births of her family, friends

and neighbors, and grieving the many

losses. Hers had truly been a life

of caring for others, though she

didn’t think much about it. It had

all come naturally.

As

the years went on, her grandchildren

were marrying, raising their own

families, and moving on. As she got

older, Suse began to feel as though

she was in the way at the old farm

home. She couldn’t do the work that

she one had. Life was quickly

passing. She had stayed awhile with

Ada, Ed and Dudley. Ada’s son,

Colby, had married Erva Miller and

moved to Searsmont Village.

Etta

and Fred had invited Suse to stay

with them. As Suse rocked in her old

chair that she had brought from the

farm, with her arms folded as though

cradling an infant, Etta stepped

into the parlor to check on her

mother. Etta told Suse that it had

been snowing very hard since the day

before. It was looking very much

like a blizzard. “I’m so very

tired!”, Suse said as Etta went

about doing her housework. Suse

closed her eyes. She missed Mose.

They’d had a good life together,

working the farm, and raising so

many children. She and Mose had

loved all of them.

It

all had been so long ago, or was it?

Was that Mose’ voice she heard?

There they all were, waving to her

from the golden shore, with Jesus

and the angels welcoming her home,

saying, “Well done, thou good and

faithful servant! Enter into the joy

of the Lord.” There would be no

parting here, no tears, and no

grief. What a happy homecoming!!! It

was Thursday, the thirteenth day of

March 1924 at seven in the evening.

The day had cleared, but the snow

was blowing and drifting. Suse had

recently passed her eighty-seventh

birthday.