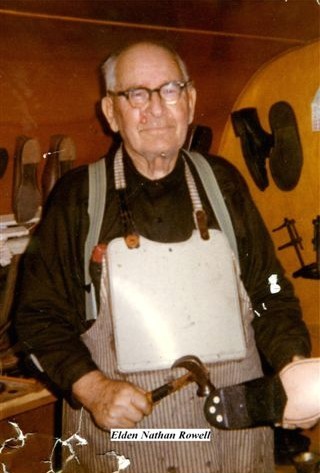

“Come eat, Elden. I’ve got your favorite

meal”, called Lois from the small

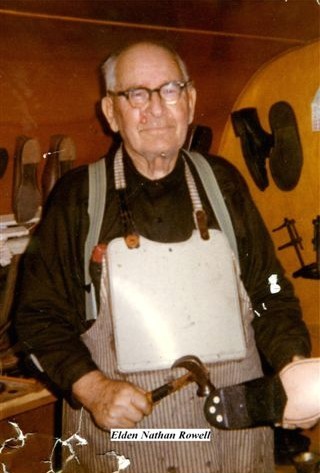

trailer-home kitchen. Elden slowly rose

from the easy chair where he had been

resting that Saturday evening, to sit down

at the kitchen table where Lois Jones

served him baked beans, slow-baked with

molasses, mustard, with plenty of salt

pork. She set down a plate of hot biscuits

with real butter. Then came a piece of

fresh-baked custard pie.

Lois and Arthur Jones had

been awfully good to Elden in his

declining years after he’d foolishly given

away his little house on the banks of

True’s Pond. In the house on the site

where he had been born, he had three

rooms, a kitchen with a large polished

Clarian wood-burning cook stove, a small

bedroom, and his cobbler’s shop in the

room across the back of the house.

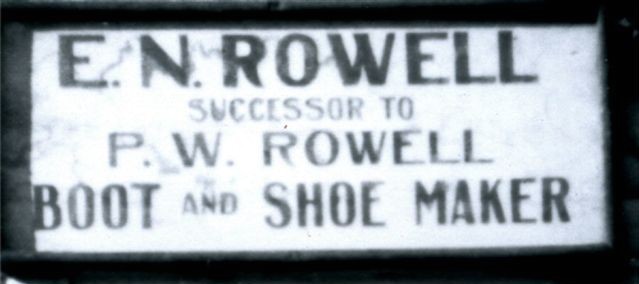

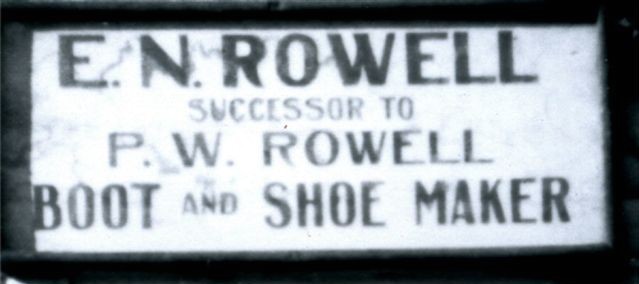

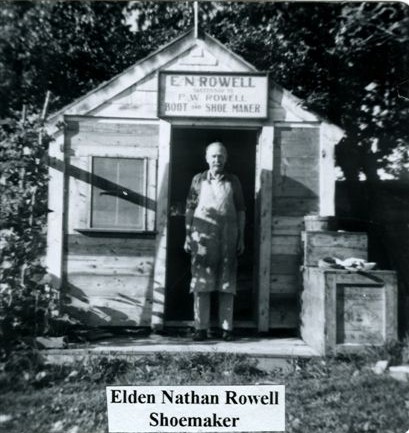

After supper, Elden

returned to the easy chair, closed his

eyes, and reminiscence of the many

adventures of his lifetime. He had lived a

colorful eighty-plus years. Elden enjoyed

telling tales to spell-bound listeners at

the only octagonal-shaped retired post

office in the United States, which housed

the Liberty Historical Society. He had

donated many of his cobbler’s tools to

them, along with the large sign which

read, “E. N. ROWELL, successor to P. W.

ROWELL, BOOT and SHOE MAKER”.

After supper, Elden

returned to the easy chair, closed his

eyes, and reminiscence of the many

adventures of his lifetime. He had lived a

colorful eighty-plus years. Elden enjoyed

telling tales to spell-bound listeners at

the only octagonal-shaped retired post

office in the United States, which housed

the Liberty Historical Society. He had

donated many of his cobbler’s tools to

them, along with the large sign which

read, “E. N. ROWELL, successor to P. W.

ROWELL, BOOT and SHOE MAKER”.

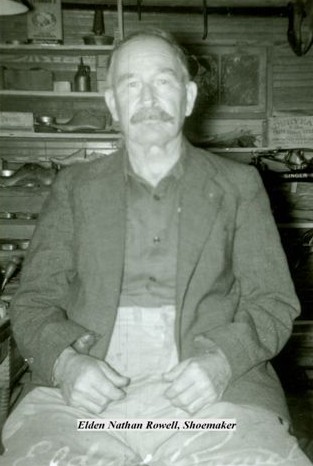

Elden had a remarkable

memory. He could recall the streets of

Liberty, Maine in the early Twentieth

century as though he was walking through

them as he talked. There was the Tannery,

the wood-working shop of Lucius Morse,

where caskets were made and sold, the

woolen mill, stave mill, ax factory,

foundry spring shop powered by water

power, grist mill to grind grain into

flour, broom factory, dance halls, stages

for traveling shows, Knowlton’s tin smith

shop, sliding and skating parties, and the

canning factory where he had been a night

watchman. Elden’s memory of life back then

was so vivid that he’d drawn sketches of

how he remembered the town.

Elden had been born just

down the road from Liberty Village over

the line in Montville, in 1890, the son of

Charles M. and Ida (Sanborn) Rowell. He

had attended the Liberty schools until he

was eighteen years old. His parents

decided to live apart when Elden was two

years old. His father raised Elden and his

two brothers in a house where no woman

resided.

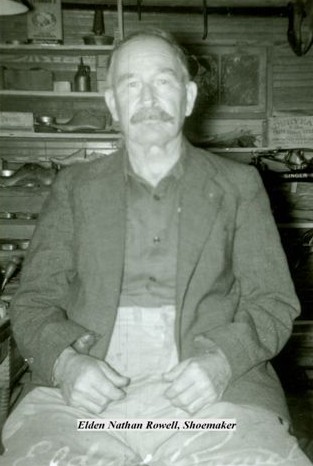

Charles’ brother,

Philander “Wheeler” Rowell had taken over

the cobbler business from their father.

From the time that he was a small child,

Elden had observed his grandfather, and

later his uncle, make shoes and boots. The

family had the cobbler bench, tools to do

‘Saddle-stitching’, hammers, knives,

punches and everything to make a pair of

shoes or boots from a piece of ‘tanned’

leather. The soles were pegged on with

wooden pegs which measured about

five-eighths of an inch long.

Uncle Wheeler would let

Elden work with the leather scraps and

tools from the time he was very young.

When he was thirteen years of age, he

became an apprentice. By the time that he

was fifteen, Elden considered that he was

old enough to go into the cobbler business

by himself. He was taking orders to make

handmade shoes and boots. He could make

three pair in a long ten-hour day, for

which he got $3 for a pair of shoes and $4

for a pair of boots.

But Elden was restless,

wanting to see more of the world than

Liberty Village and South Montville with

its water-powered mills offered.

On a hot August night in

1908, he and some young friends were

drinking hard cider together. Elden

decided that if he had a dress suit, he

could make his way in the world. That very

night Hollis L. Jackson’s General Store in

South Montville was broken into. All that

was taken was a suit of clothes, a

revolver, and some small incidental items.

Elden had left Liberty. His ‘friends’ told

the Sheriff that Elden Rowell had been

looking for a suit of clothes. The

officers began searching for a

well-dressed, armed culprit.

On a hot August night in

1908, he and some young friends were

drinking hard cider together. Elden

decided that if he had a dress suit, he

could make his way in the world. That very

night Hollis L. Jackson’s General Store in

South Montville was broken into. All that

was taken was a suit of clothes, a

revolver, and some small incidental items.

Elden had left Liberty. His ‘friends’ told

the Sheriff that Elden Rowell had been

looking for a suit of clothes. The

officers began searching for a

well-dressed, armed culprit.

One Monday afternoon, the

Sheriff stepped up to Elden, as he left

the Schooner operated by Capt. Fitz

Patterson, in Belfast, Maine, and asked,

“Are you Elden Rowell?” Elden replied,

“No, I never heard of him.” “Do you come

from Liberty, Maine?” was the next

question. “No”, replied Elden. “I’ve never

been in Liberty in my life.” A man stepped

forward from the crowd, who identified

eighteen-year old Elden Rowell.

Consequently he was arrested and taken off

to jail.

After that escapade,

Elden decided to “go to sea”. He worked as

a deck hand on the sailing ships for

several years. He had even sailed the

South Seas. In 1915, while Elden was

at home in Liberty, he married Leola

Choate.

In Portland, Maine, on

the fourth of July, about 1924, he and a

shipmate went ashore. They went to a

Sparks Brothers Circus that was in town.

After purchasing tickets, they saw a “Men

Wanted” sign. They were immediately hired,

fed a hot meal, and began hoisting tent

poles of the large Three-Ring circus

tents. The next morning his friend was no

where to be found. Elden assumed that the

friend could not do the hard work, and

went back to the ship.

Elden stayed on traveling

with the circus during the summers,

working on the “Big Top” tents, keeping

them in repair, as well as leather harness

work. In the winters, ‘Whitey’, as he was

now called by the circus people, worked in

the harness shop at the winter quarters in

Macon, Georgia. Elden had been in every

state in the continental United States,

Canada, and down to Mexico.

After being away from

home for a few years, one evening Elden

walked into the home that he had shared

with Leola. She stood at the stove

preparing a meal, obviously expecting

another child, with a man seated at the

kitchen table. Elden threw his hat into

the corner, pulled up a chair and said,

“What’s for supper?” After eating the

evening meal, he donned his cap, gathered

up his meager belongings and traveled on

his way. He and Leola divorced.

The Sparks Brothers

Circus eventually got a gas-powered engine

to drive the large tent stakes, which

became ‘Whitey’s’ job for about seven

years. Elden sported tattoos on his

large biceps. He got his favorite tattoo

at The Bowery in New York.

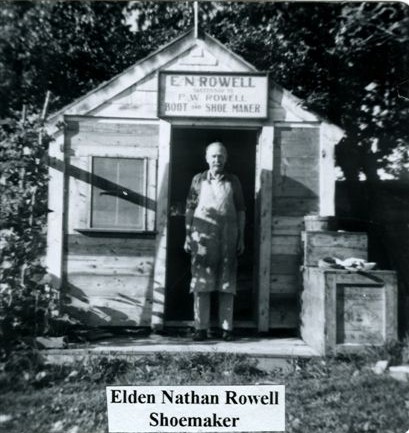

The Coast of Maine was

calling Elden home. He was tiring of the

constant travel. After all, he was a

pretty darn good cobbler. There was plenty

of work back home in Maine, making boots

and shoes. His Uncle P. W. Rowell, a

Master at cobbling, had died in 1911,

while Elden was away. It was time to go

home and settle down..

The Coast of Maine was

calling Elden home. He was tiring of the

constant travel. After all, he was a

pretty darn good cobbler. There was plenty

of work back home in Maine, making boots

and shoes. His Uncle P. W. Rowell, a

Master at cobbling, had died in 1911,

while Elden was away. It was time to go

home and settle down..

In 1926, Elden married a

home-town girl, Bertha M. Davis.

Apparently he wasn’t cut out for married

life, perhaps because of his all-male home

life from his early youth.

Elden remembered that in

his younger days, when he returned from

being a ‘roustabout’ with the Starks

Brothers Circus, he drank hard liquor way

too much. In fact, he called himself “the

worst drunk in town”. He’d given up

drinking many, many years ago. He had

friends who’d say, “Join me in a drink. A

little drink won’t hurt anyone.” His reply

was, “A little drink leads to a lot of

drinks!” and he figured that he didn’t

have to drink to have friends.

Elden recalled walking to

Camden from Liberty, stopping at

Wentworth’s store on Moody Mountain for

his tobacco, and spending the night in a

barn before traveling on his way. The

farmer might never have known that he’d

been there. He might eat an apple or a

vegetable stored in the barn. He’d be

careful not to start any fires, which he’d

have no need to do, as he never

smoked. If Elden had a vice, it was

chewing tobacco. Visitors saw him spit a

stream of ‘tobaccy’ into a saw-dust filled

can, or from the front step, missing his

cat. Of course, if he’d wanted to hit his

cat, he could have.

Once he settled down in his

own little house, he’d always had a cat.

The cat would keep rodents from the house,

as well as being great company. Once when

Elden was given a can of Spam, he shared

the contents with his cat. The cat refused

to eat it. Elden said that if the cat

wouldn’t eat it, then it warn’t fit’n to

eat.

Once he settled down in his

own little house, he’d always had a cat.

The cat would keep rodents from the house,

as well as being great company. Once when

Elden was given a can of Spam, he shared

the contents with his cat. The cat refused

to eat it. Elden said that if the cat

wouldn’t eat it, then it warn’t fit’n to

eat.

In his cobbler shop,

Elden made leather heels for the shoes. He

could not understand why people complained

that leather soles were slippery. “Why,”

he commented, “The whole United States was

built on leather.”

In his latter years,

Elden thoroughly enjoyed going to the

Liberty Historical Society, where he sat

and spun tales. No one ever knew if he

embellished on these tales or not. One

tale that he delighted in telling was

about Martin Hannan of Company B of the

Nineteenth Regiment of Maine Volunteers,

who had hung his scythe in a tree in

Montville and gone off to fight in the

Civil War.

Elden recalled that

Martin was a very smart sharpshooter.

Elden had been fourteen years old when

Martin died, having lived in the same

neighborhood. Martin Hannan was a poor

man, who had been wounded in the Civil

War, raising a large family, bringing many

shoes to be repaired at Uncle Wheeler’s

cobbler shop. While waiting for the shoe

repair, Martin had told the young Elden

that when he served in the Civil War,

there was a certain spring of water where

the soldiers filled their canteens, and

knelt down to drink the sparkling water. A

Rebel soldier, who had hidden himself in

the bushes, picked off the Yankee

soldiers, one by one at the spring. A

Union General said that he’d give $100

bounty and promotion to the rank of

Sergeant to any man who could bring in the

Rebel, dead or alive. Elden recalled that

Martin camouflaged himself as a tree,

waiting patiently for the Rebel to appear.

His patience was rewarded when he “did

away” with the sniper. He sent the $100

home to purchase the 100-acre Lermond farm

next-door to his parents’ farm in South

Liberty. Martin soon received the papers

promoting him to Sergeant. Elden delighted

in showing Martin Hannan’s great-grandson,

Bob Maresh, the tree in Montville where

Martin had hung his scythe on the fateful

day in July of 1862 and gone off to War.

Elden enjoyed company and

regaled them with his many tales. Elden

recalled Martin Hannan’s grand-daughter,

Gladys, coming home from Massachusetts for

summer vacation with her Russian-born

husband, Tony Maresh and children. Elden

told Bob that he remembered when he, Bob,

was a three-year old and was very worried

about stepping on the “Flowters” on the

lawn. The “Flowters” were dandelion

blossoms. Elden chuckled when he said that

Bob could trip over the “Flowters” in a

linoleum. He chuckled much as he told his

tales.

When a customer brought a

pair of shoes to be repaired by his

skilled workmanship, Elden carefully

labeled them. If he was going away, he

would put out his sign, “DON’T LEVE NO

SHOES” with a big padlock on the door.

He’d take a cart, hauling the repaired

shoes to Abbie Hannan below the Village to

deliver to the right customer. He knew

that he could trust Abbie, but there were

a few people that he couldn’t trust “as

far as he could throw them”. He’d make the

mistake of over-trusting a few times in

his life.

When a customer brought a

pair of shoes to be repaired by his

skilled workmanship, Elden carefully

labeled them. If he was going away, he

would put out his sign, “DON’T LEVE NO

SHOES” with a big padlock on the door.

He’d take a cart, hauling the repaired

shoes to Abbie Hannan below the Village to

deliver to the right customer. He knew

that he could trust Abbie, but there were

a few people that he couldn’t trust “as

far as he could throw them”. He’d make the

mistake of over-trusting a few times in

his life.

Elden was a man of many

talents, but these days, after nearly nine

decades of life, he just enjoyed people.

He said that people didn’t bore him, but

they amused him. He told visitors that

he’d lived past the ‘dying age’. He was

ready to die and had no regrets abut how

he’d lived his life. If he had it to do

over, he would just live more of it. He

loved to go on rides with friends,

especially his younger friends.

Elden had made himself a

gravestone. He said that they could put it

on his final resting place, and he didn’t

care where that would be. They could bury

him anywhere.

Elden enjoyed his final

years with the Jones’ family. They were

good to him. Elden Nathan Rowell passed

away on Wednesday, May 23, 1979, at the

Waldo County General Hospital in Belfast,

Maine, aged 89 years. His final resting

place is in the Hunt Cemetery in Liberty,

just a short way from where he was born

and raised, from where he later had his

cobbler shop, and from where he spent his

last days with the Jones family. He had

lived an adventurous life, as he said,

“With nothing to be ashamed of”. He had

lived when Liberty, South Montville, and

Montville were bustling communities of

factories, mills, stores and prosperity to

a time when the major roadway by-passed

the towns, leaving them as peaceful little

retirement communities. That is progress!

After supper, Elden

returned to the easy chair, closed his

eyes, and reminiscence of the many

adventures of his lifetime. He had lived a

colorful eighty-plus years. Elden enjoyed

telling tales to spell-bound listeners at

the only octagonal-shaped retired post

office in the United States, which housed

the Liberty Historical Society. He had

donated many of his cobbler’s tools to

them, along with the large sign which

read, “E. N. ROWELL, successor to P. W.

ROWELL, BOOT and SHOE MAKER”.

After supper, Elden

returned to the easy chair, closed his

eyes, and reminiscence of the many

adventures of his lifetime. He had lived a

colorful eighty-plus years. Elden enjoyed

telling tales to spell-bound listeners at

the only octagonal-shaped retired post

office in the United States, which housed

the Liberty Historical Society. He had

donated many of his cobbler’s tools to

them, along with the large sign which

read, “E. N. ROWELL, successor to P. W.

ROWELL, BOOT and SHOE MAKER”. On a hot August night in

1908, he and some young friends were

drinking hard cider together. Elden

decided that if he had a dress suit, he

could make his way in the world. That very

night Hollis L. Jackson’s General Store in

South Montville was broken into. All that

was taken was a suit of clothes, a

revolver, and some small incidental items.

Elden had left Liberty. His ‘friends’ told

the Sheriff that Elden Rowell had been

looking for a suit of clothes. The

officers began searching for a

well-dressed, armed culprit.

On a hot August night in

1908, he and some young friends were

drinking hard cider together. Elden

decided that if he had a dress suit, he

could make his way in the world. That very

night Hollis L. Jackson’s General Store in

South Montville was broken into. All that

was taken was a suit of clothes, a

revolver, and some small incidental items.

Elden had left Liberty. His ‘friends’ told

the Sheriff that Elden Rowell had been

looking for a suit of clothes. The

officers began searching for a

well-dressed, armed culprit.  The Coast of Maine was

calling Elden home. He was tiring of the

constant travel. After all, he was a

pretty darn good cobbler. There was plenty

of work back home in Maine, making boots

and shoes. His Uncle P. W. Rowell, a

Master at cobbling, had died in 1911,

while Elden was away. It was time to go

home and settle down..

The Coast of Maine was

calling Elden home. He was tiring of the

constant travel. After all, he was a

pretty darn good cobbler. There was plenty

of work back home in Maine, making boots

and shoes. His Uncle P. W. Rowell, a

Master at cobbling, had died in 1911,

while Elden was away. It was time to go

home and settle down..  Once he settled down in his

own little house, he’d always had a cat.

The cat would keep rodents from the house,

as well as being great company. Once when

Elden was given a can of Spam, he shared

the contents with his cat. The cat refused

to eat it. Elden said that if the cat

wouldn’t eat it, then it warn’t fit’n to

eat.

Once he settled down in his

own little house, he’d always had a cat.

The cat would keep rodents from the house,

as well as being great company. Once when

Elden was given a can of Spam, he shared

the contents with his cat. The cat refused

to eat it. Elden said that if the cat

wouldn’t eat it, then it warn’t fit’n to

eat. When a customer brought a

pair of shoes to be repaired by his

skilled workmanship, Elden carefully

labeled them. If he was going away, he

would put out his sign, “DON’T LEVE NO

SHOES” with a big padlock on the door.

He’d take a cart, hauling the repaired

shoes to Abbie Hannan below the Village to

deliver to the right customer. He knew

that he could trust Abbie, but there were

a few people that he couldn’t trust “as

far as he could throw them”. He’d make the

mistake of over-trusting a few times in

his life.

When a customer brought a

pair of shoes to be repaired by his

skilled workmanship, Elden carefully

labeled them. If he was going away, he

would put out his sign, “DON’T LEVE NO

SHOES” with a big padlock on the door.

He’d take a cart, hauling the repaired

shoes to Abbie Hannan below the Village to

deliver to the right customer. He knew

that he could trust Abbie, but there were

a few people that he couldn’t trust “as

far as he could throw them”. He’d make the

mistake of over-trusting a few times in

his life.