Lincolnville,

Maine was home to a multi-talented man,

who made his way to San Francisco when it

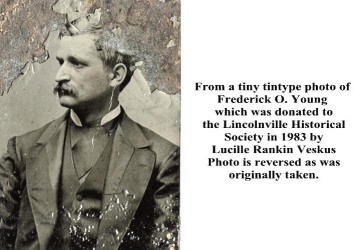

was a fledgling city. Much of the

biography of Frederick Osborne Young,

commonly called F. O. Young, was written

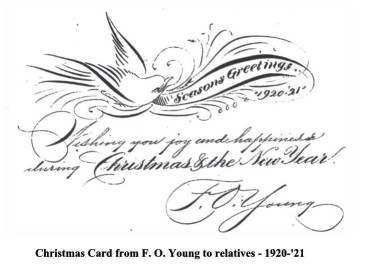

in his own words, in letters that he wrote

to relatives, newspaper clippings as told

to reporters, and in pages of his diaries

of 1922, which were in the possession of a

relative, Gus Ossman. F. O. Young’s

life story has been written about in

Lincolnville Historical Society’s

publications, and in the Young

Genealogical Workbook, in 1991 by

Donald L. Young, Jackie (Young) Watts and

Isabel Morse Maresh.

Yet, there are those who

have never heard of him, and how he

overcame many, many obstacles in his life.

Here is his story, much of it as

told by him:

I was born in Youngtown in

Lincolnville, Waldo County, Me. on March

13, 1852. I was the second child of

ten children of Elijah Young and Nancy

Annville Heal.

I seem to

have been born under an unlucky star as I

had many accidents in my youth. The

first was when I got lost on our

celebrated turnpike [the road from

Lincolnville to Camden, by Meguntcook

Lake]. I was about two and a half

years of age. They found me about 3

o’clock in the morning. I was found

where I had climbed up the mountain side

from the road. I was asleep on a rock and

half-dead. They had fired guns and

about given up, thinking that I might have

drowned in the pond when through a dream,

Uncle Doctor, the seventh son of Moses

Young, found me. I remember coming

to life when they were taking me home in

the wagon.

When I

was about four years old, my mother gave

me a whipping for getting inside of

Grandfather’s clock. The end of the

switch, about three-eighth-inch long, got

into my right eye, and staid there for

nine days. It hadn’t penetrated the

eye, and could have been removed if the

doctor had come, but he said to poultice

it, and it ruined my eye.

Grandfather said that he could have

pulled the piece from my eye, but Mother

was sympathetic with my pain, and wouldn’t

let him.

When I was

nearly six years of age, Father was

chopping wood in the shed. I wanted to go

out of the door beyond him. There was a

narrow space between his chopping block

and a tier of wood. I darted thru in front

of him, while his axe in the air just

missed me and took my right hand off in

the air like a twig, mitten and all.

My

Grandmother Young [Charlotte (Heal) Young]

came up, and the excitement brought on a

shock of palsy from which she died on that

day, Jan. 17, 1858. Grandfather told

me that he saved the thumb on my right

hand. Dr. Gordon had wanted to cut

it off at the wrist. Grandfather

said that it would be more than a hand to

me. He was a practical man and saved me

from failure. Without it, I would

have been poor indeed. I can pick up

a pin, button a button, in fact, those

around and working with me never notice my

disability. Doctors should be very

careful in such cases and save if possible

a remnant.

When I was

older, I was helping father build our

barn. I slipped and fell ten feet headlong

into the barn floor. It nearly broke

my neck and laid me up for a long time.

This was due to my eye, in

miscalculating distance as anyone knows

you lose the angle of the two eyes.

Try and place your finger on an

object while shutting one eye and see for

yourself. I climbed a tree fifteen

feet where I threw my right arm over a

rotten branch and fell to the rock below

which laid me up for a long time.

In chopping

down small trees, I smashed my finger

badly and the only consolation I got from

Father was: Why didn’t you keep on

chopping? Once he put the broad axe

into his foot while working in the

shipyard and he poured turpentine into the

great gash and went on hewing.

That’s the kind of men who make

things go. When I was sixteen, I was

wrestling with a man about forty pounds

heavier than I, though I threw him.

In doing it I slipped on the ice and

was lame for a year in my back.

Mother said, ‘Good enough for

you, you shouldn’t wrestle. ‘

All sports

were meat and food for me and I practiced

exercises at home so as to outstrip my

mates. Another time I was chip

chopping with a mate and my axe stuck, and

his axe nearly severed the fingers of my

left hand. The same mate stabbed me

near my juggler vein. I also had two

severe cuts from my scythe. I

knocked my big toe joint out and was lame

for three years. I wrenched my ankle

in jumping over a high wall which put me

on crutches for a time.

I was thrown

from a horse which hurt my side badly.

I dropped a pistol and was shot thru

my right arm, smashing the bone.

This wasn’t well before I thrust a

big pin into my foot. I liked to

have died from blood poison. In this

case, I had only one foot and one hand

left to help me around on my crutches.

I’ve never had a fight in my life

but always was willing to measure up with

my mates in a sportsman-like way to decide

our ability, with no desire to injure or

to be injured having grown cautious from

experience. I lay the loss of my

hand and other accidents to having lost my

eye, as I couldn’t see my danger in that

side and later was run over by a heavy

team from the same cause.

I went to

school three or four months of the year.

I worked on our small farm and

neighboring farms and in Camden until I

was about nineteen years old. I then

went to the Castine State Normal School,

where I graduated in 1874. While I

was attending this school, and afterward,

I taught winters in about sixteen towns in

ten years. I taught singing and

writing schools evenings. During

vacations I worked haying, farming,

carpentering and at any work that I could

get. The principal of the Normal School

found me proficient enough in vocal music

to give me the primary class in music.

I taught while there, earning enough

by being economical with vacation work and

teaching to pay my own way. The

first money I earned at $15. A month

with Cal Joe Fry Hall. He offered me

the money to go the school. I

thanked him for his interest in me, and

told him that I had saved money enough to

go to Castine.

During the

summer I also went mackerel fishing.

I became proficient enough to go

High line on my last two trips. My

best catch with handline was ten stave

barrels in one day, and that was in a

fourth-class berth. Eben Loveland,

our first hand, caught eleven barrels at

the same time. By working at these

different occupations I managed to get a

little money ahead, and finally, after

seeing some of Gaskell’s fine penmanship,

I went to his college at Manchester, NH.

He gave me praise, and said he said

that I had a fortune in my left hand, and

that he made as much money in advertising

me as he did from learning from his

Compendium.

After

publishing my portrait and a write-up in a

daily paper, he conceived the idea of

publishing them in his Gazette. It

was an incentive to thousands, many of

whom became prominent penmen, but I was

before them. I have outlasted nearly

all of them, and probably have done more

practical penmanship than any living man,

yes, any two ever did. None believed that

a left-handed man could do it. The

secret of it was that I used the muscle or

forearm instead of fingers. By that

means I could do the heaviest work and

still retain my writing. The leading

penmen laughed at it, but I have taught

right-handed persons with my method and

had wonderful success.

Mr. Gaskell

considered me the best left-hand writer in

the United States. He said that the

most interesting part of this writing is

that I turned the paper round until the

ruled lines are vertical, the head of the

sheet being by my right hand, then turned

the left side of my body toward the desk,

and wrote down the vertical lines toward

my body. Mr. Gaskell told a reporter

when completed, the sheet is turned round

and the letter if found in the ordinary

shape and with all the letters sloped as

if written by a right-handed person.

Mr. Young is a young gentleman of

education, and has been a successful

teacher in Maine. He unhesitatingly

declares the elegances of his penmanship

are entirely attributable to his study of

Gaskell’s Compendium. He has only

been about a week a student at the

business college.

Now after

fifty years, they are trying to teach

penmanship all over. But they don’t

get at it as I did and still do, for I can

duplicate anything done with the pen.

At seventy

years of age, I can do two hundred

diplomas in a day, what it took three of

us, A. R. Dunton, I and an assistant, to

do in two days, and I have been an invalid

for six years. I have lost eighty

pounds in weight. So much for my

practical work. I was gifted with

fine eyesight, being able to write the

Lord’s Prayer six times on a silver half

dime, which was once and eight words,

claimed to be the record by a man who used

two pair of specs.

I was also

gifted with a fine constitution from my

New England Yankee parents of which there

were none better, being able to do all

that pertained to our primitive mode of

living, having to farm, carpenter, spin,

weave, knit, cook, wash and make nearly

everything we need in the first years of

my life.

How many

times I’ve seen Mother spin till 11

o’clock at night. She always had

some work in the evening after all the

work of the day. Caring for a family

of ten children is some job. Father

was a mighty man. He never let me

sit in the corner and suck my thumb,

though I had one hand and one eye.

But he put the lash to me, and

finally I got so I could lead him in the

hay field. We need not be ashamed of

our old-fashioned New England parents.

They have produced the children who

have made this country. May the Lord

save us from producing a degenerate race,

for it is fast superseding our good old

stock, physically, mentally and

mechanically. But for our early

training among the rocks and ribs of

Maine’s hills, I never could have stood

the strain of my work and survived.

Teachers and penmen with much less

work I have seen pass out, though I was

before them at the work. I thank my

Dad for making me hoe my row and keep up

now, though I rebelled sometimes when I

was not allowed more time to play.

I also became

a sharp-shooter. Major F. O. Anderson,

Editor of The Penman’s News-Letter,

who called me the Marvel of the Ages wrote:

Mr. F. O. Young was not only a great

penman, but one of the greatest marksmen

of all times. He held the world’s

record for musket shooting, having made

459 out of 500, against the former

champion, Chris Meyer. He made 98

bull’s eyes out of 100 shots. At 200

yards offhand shooting, he has never been

equaled. Mr. Young used a

fifteen-pound Ballard rifle. He held

the world-record of The Columbia

Pistol and Rifle Club, with the fine

rifle at the Shellmound Range, where he

fired two scores and made five, and four

on the Columbia target. The latter

score had never been equaled.

As F. O.

Young grew older, he wrote to a relative:

Dear Cousin: I note your writing is

improving. My eye is growing dim.

I can see about seven inches without

specs to write and read. What an eye

I had! And so abused. It got

near-sighted and I went into long range

shooting to lengthen it and it did.

Then I had to put on glasses until

it came back to original sight. So I

put on distance specs but it is hazy and

the optician can’t fit me, so I am up

against it. But I am thankful that

it is as well as it is. Just

consider that during the past fifty-five

years I’ve written about 2,000,000 cards,

50,000 diplomas, and engrossed over 50,000

pieces besides all my letters, flourishes,

drawings, signs, etc, etc. After two

penmen who had learned from me played out,

I took their place in the Emporium and

wrote for fifteen years under a two-power

electric. I wrote the Lord’s Prayer

six times in the size of half dime,

without specs. My competitor used

two specs and wrote it four times. He

claimed the record.

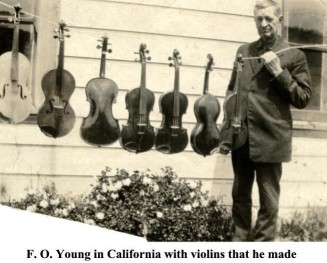

Another of F. O. Young’s hobbies

was making fine violins. It seemed

that there was nothing that he could not

do. His violins, his Sharp-shooting

pistol, many, many of his penmanship

drawings are among his relatives.

Some have found their way to the

Lincolnville Historical Society, and have

been displayed at the Farnsworth Museum in

Rockland, Maine.

|

|

|

A

newspaper clipping titled Expert

With Pistol And Pen summed

up his life: Mr. F. O. Young, the

California representative of the

Sharpshooters Union, Newark, N.J.

is a Maine man, with one eye and

one hand. His father

accidentally chopped off his right

hand when he was a small boy and

his mother knocked his right eye

out whipping him for getting

inside his grandfather’s clock.

He never traveled on a

railroad without an accident of

some kind happening. He has

been mauled by wildcats, hugged by

bears, bitten by rattlesnakes,

thrown from bronco ponies a

hundred times, frozen so often

that he has become accustomed to

it. He was struck by

lightening and had both feet

shattered, and has been gored by a

Durham bull. Mr. Young, in

modestly relating his experience,

said he was beginning to be afraid

that something serious might

happen to him some day. Mr.

Young was one of the successful

shooting competitors and won a

gold and silver medal and numerous

other prizes. He is the

finest pistol shot on the Pacific

Coast, and is also recognized as

the champion left-handed penman of

the world.

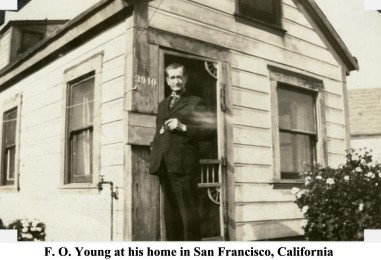

Fred

Osborne Young died May 15, 1932 in

San Francisco, California, aged 80

years and 1 month. One

reporter wrote of him as being One

of our Lincolnville boys who now

sleeps among his kindred in the

family lot in the Youngtown

Cemetery in Lincolnville, Maine.

|

[Postscript:

Lincolnville Historical Society welcomes

contributions of any data relating to F.

O. Young, as well as other Lincolnville,

Me. Artifacts.]

|